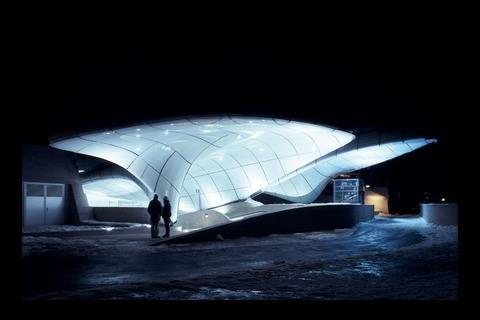

Zaha Hadid evokes duvets, wings and ice with her designs for Innsbruck’s cable car stations

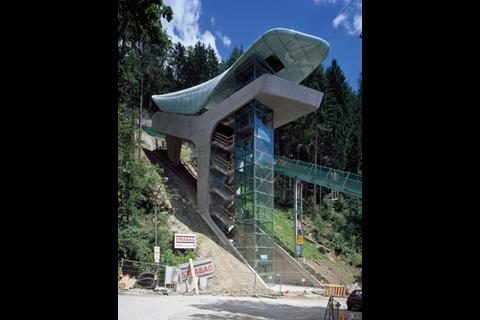

Zaha Hadid’s penchant for free-form sculptural eruptions has been given full vent at Austria’s Alpine city of Innsbruck. On the strength of her spectacular Bergisel Ski Jump of 2002, the city council invited her to compete for four stations on the 1.8km Nordpark Cable Railway.

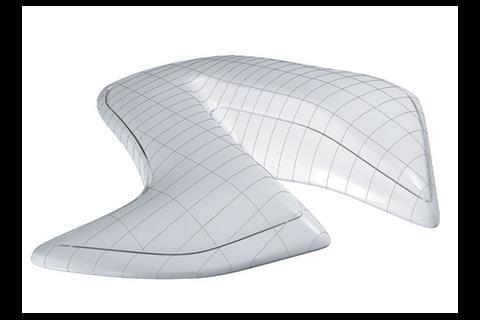

Her winning *50m (£36m) scheme, which opens next week, is in a soft, fleshy, curvaceous mode that has taken over from her hard, spiky, gothic style. The roof canopies that float over the open-air stations evoke plumped-up duvets, warped aircraft wings, or more appropriately to their Alpine setting, ice formations left by a retreating glacier. Each station is different, depending on the incline of the cable track at that point, yet as project architect Thomas Vietzke explains, they coalesce as a family of curvaceous, organic forms.

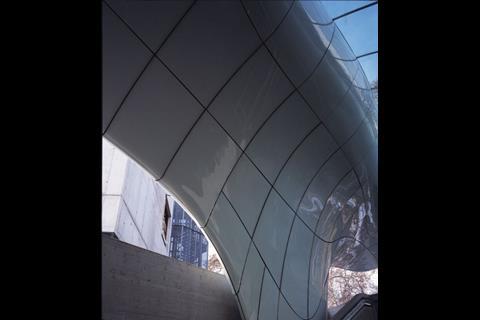

The moulded, double-curved shapes may suggest that they are made of fibreglass, which is quite happy to be pummelled and filled to achieve the desired shape of a yacht, or Future Systems’ Lord’s Media Centre. But the material used for these canopies is far more brittle and unforgiving: it is pure glass. This gives the canopies a polished, lustrous finish, just like ice. Toughened glass also has the practical benefit of being durable and resistant to knocks from falling rocks or trees.

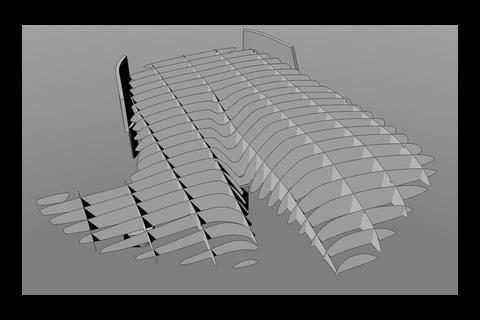

Not surprisingly, the design pushed advanced glass technology to its limits. In construction method, the canopies really do resemble aircraft wings, as the skin has been wrapped all around parallel steel ribs spaced at 1.25m intervals. The big difference is that glass could not simply be riveted to the steel ribs to assume its double-curved shape.

Instead, it had to be made up of a series of rigid panels, all fabricated to the same 1.25m dimensions as the spacing of the ribs. Far more tricky than that, each glass panel had to be moulded precisely to its final double-curved shape, while softened by heat at the glassworks. A total of 850 glass panels totalling 2,500m2 in area were used to cover all four stations, and each panel was unique in its sculptural form.

Some of the panels even come with a continuous recess or trough, with a radius as tight as 60mm, to serve as a rainwater gutter sunk into the canopy’s top surface and leading to a conventional downpipe concealed inside. As Vietzke comments: “The fluid shapes of the canopies lend themselves naturally to the flow of water.”

The glass technology was developed by structural engineer Bollinger & Grohmann, of Frankfurt and Vienna, and manufacturer Pagitz Metalltechnik, of Klagenfurt, although the panels were actually made in China using computer-numerical-controlled (CNC) machines linked directly to the design team’s CAD system in Europe.

The basic material of the manufacturing process was a series of flat panes of 12mm thick glass. Moulds were made out of steel rods contoured to the precise double-curved shape of each panel. Then an 8mm thick glass pane was made pliable with heat and laid over the countoured bed as an underlayer to mooth out bumps and imperfections.

After that the final pane was laid over the underlayer. Next, a 1.5mm thick layer of white polyurethane resin was laminated to the underside of the panel to hold the glass together in case it shattered and give it a strong white appearance. All the panels were prefabricated to a tolerance of ±3mm and after manufacture, their precise shape and dimensions were checked by a 3D digital scanner.

The assembly method on site was at least as ingenious and even more complicated. Hadid wanted the curved outer surface of the canopies to be streamlined across all the panels, uninterrupted by gaps, steps or bolt-heads.

A secret fixing system was devised in which stainless-steel cleats were bonded with adhesive to each panel so that they that would project slightly from the edges.

At the same time, a 93mm-thick strip of polyethylene that had been pre-formed by CNC to the precise curvature of each panel, was bolted around the outer edge of each steel rib. When each panel was offered up to its final position on-site, its projecting steel cleats were screwed into polymer buffer.

Finally, the 25mm gaps between the panels were filled with black silicone that neatly concealed the cleats and screwheads.

The plinths of all four stations, as well as bridges and pylons from which supporting steel cables are hung, were constructed of in situ reinforced concrete. The plinths have flat surfaces with curved corners, and the concrete is exposed to show the texturing of the timber shuttering boards. All this gives the plinths a solid, earth-bound appearance that sets off the moulded glass canopies that float overhead.

What better lift-off could Innsbruck’s skiers ask for than passing through glacial stations like these on their way up the ski slope?

Project team

Client Innsbruck City Council

Architect Zaha Hadid Architects

Structural engineer Bollinger & Grohmann

Project manager Malojer Baumanagement

Development partner, main contractor and operator Strabag glass

Canopy contractor Pagitz Metalltechnik

Postscript

This article appeared in Building magazine as Lifting the spirits

1 Readers' comment