On the 350th anniversary of the fire’s close, Ike Ijeh shows how the disaster heralded enormous changes for architecture and urbanism despite the sidelining of Wren’s grand plan

350 years ago yesterday the Great Fire of London finally ended after ravaging the city for three catastrophic days. Despite an official and highly unverifiable death toll of six, it left a trail of devastation that was to change the face of the capital forever.

Partially as a result of this low official death toll and with its inherent quantity of drama and spectacle, history has heavily romanticised the Great Fire of London and, along with the Battle of Hastings, it is one of the few dates drummed into British schoolchildren’s heads that attains sufficient mythical status to linger in the memory long into adulthood.

Yet these snug pretensions to folklore belie the sheer horror of the event itself. It is almost impossible to visualise today the scale of destruction the Great Fire left in its wake. If we ignore the discrepancy between official death tolls, the level of devastation tragically visited upon central Christchurch after the 2011 earthquake is the kind of modern natural urban disaster that bears comparison.

As a result of the Great Fire, 80% of the city was destroyed. As were over 13,200 houses, 87 churches, the Royal Exchange, Newgate Prison, Bridewell Palace and Europe’s third largest cathedral. The conflagration left up to 80,000 Londoners homeless, almost a fifth of the city’s population at the time. This is equivalent to almost two million people in today’s capital being made homeless overnight. The psychological as well as physical impact on the city must have been immense.

But of course as we all know and as the resplendent phoenix carved above the entrance of the south transept of St. Paul’s Cathedral attests, the city rose from the ashes. Many are familiar with the ultimate failure of Christopher Wren’s ambitious plans to rebuild the city as a formal Renaissance capital and thereby assume that the new city emerged in much the same fashion as the old. This is true to an extent but does not tell the whole story.

London is a city defined by a relentless and reactive cycle of destruction and redevelopment. This stretches from the demolition and rebuilding of much of Norman Westminster Abbey in the mid-thirteenth century to solidify Henry III’s rule to the IRA bomb that destroyed the Baltic Exchange and paved the way for the Gherkin to be built on its ruins. And yet the Great Fire of London probably remains the greatest single driver of architectural change and urban innovation in the capital’s history. Here is how it did it.

Regulations

The Great Fire of London may have been the biggest and most famous conflagration in London’s history but it wasn’t the first. The current St. Paul’s Cathedral is the fifth on the site, the first was built in 605 and promptly destroyed by a fire that swept through the city just seventy years later and the third met a similar fate in a fire that consumed much of Saxon London in 1087.

As a result of this succession of disasters, which also included two major medieval fires that ravaged London in 1135 and 1212, the first Building Act was passed in 1189 with the intention of legislating standards for building materials and footprints. But contraventions were widespread and by August 1666 London was a scorched tinderbox of wooden buildings, thatched roofs and houses that leaned so closely together that eaves on either side of the street would touch.

All this changed as a result of series of measures introduced after the Great Fire of London. Rules were introduced to ensure each parish had two fire ‘squirts’, a highly primitive wheeled bucket and barrel contraption that acted as an early fire engine and set the foundation for today’s fire brigade. Equally, the London Fire Prevention Regulations of 1668 established new rules for water supply pipework and infrastructure that lay the origins for the modern fire hydrant systems of today.

But it is the post-fire London Building Act of 1667 which stands as arguably the single most influential piece of construction-related legislation in British history. Many are familiar with the broad terms of this act, regulated storey-heights, the banning of timber facades in favour of brick and stone, additional enforcement of the ban of thatched roofs (which had technically been outlawed since 1212 anyway) and an end to the practice of houses jutting out over the floor below in an attempt to minimise rents determined by ground floor footprint.

Many of these strictures formed the basis for building regulations still in force today, the roof of the new Globe Theatre was the first thatched roof permitted in London since the Great Fire itself. Equally, the 1667 Act was widely copied in a succession of acts by other British cities over the next three hundred years before being collectively codified into national legislation in 1965. But the real mettle of the 1667 Act lay in one crucial statute, for the first time money was to be allocated for the state to employ surveyors to enforce the regulations. Thus the humble building control officer, as well as our entire modern building control system, was born.

Churches

In our increasingly secularised world it is easy to forget the sheer social and physical power churches once wielded over British society. In much the same way that a supermarket is now an essential component of any new housing development or urban plan, for the nineteen centuries before the 20th century, that essential component was a church. And the Great Fire of London harnessed prevailing political winds to revolutionise their design and rewrite their impact on the city.

Of course the most significant church rebuilding enterprise associated with the Great Fire and the masterpiece of Christopher Wren’s astonishing career is St. Paul’s Cathedral. And rightly so. Well over three hundred years after its construction the cathedral is known the world over as an indelible symbol of London and such is its power that the iconic photograph of its famous dome rising above the smoking ruins of a Blitzed London was harnessed by British and German wartime propaganda as a powerful symbol of resistance and success respectively.

St. Paul’s is also probably the single most internationally influential piece of architecture this country has ever produced. It reversed a six hundred year cycle where England had largely imported then Anglicised European architectural styles and its fingerprint extends from the Pantheon in Paris through to the U.S. Capitol, St. Issac’s Cathedral in St. Petersburg and multiple other imitations across the world.

Yet, such is the legacy of St. Paul’s that it is easy to forget the 52 other churches Wren rebuilt for London after the fire, the individuality of each one a testament to his astonishing capacity for ingenuity and inventiveness. In their clever tempering of baroque vivaciousness with a more rational, structural dynamism they forged a new template for an emergent Protestant church that, through the work of architects like James Gibbs and John James in the following century, was exported across the English-speaking world.

Today, only 24 of Wren’s churches remain in their entirety and there are remnants of a further six. Many where destroyed on a single night in the Second World War, the 29th December 1940 which marked the peak of the Blitz assault on London and is sometimes referred to as the Second Great Fire of London. With its office buildings and towers the City of London is today overwhelmingly associated with commerce. But the Great Fire also reinforced a strong spiritual identity that lingers quietly in Europe’s greatest collection of baroque churches anywhere outside Rome.

Skyline

Prior to the Great Fire of London London’s skyline was a chiefly characterised by a collection of churches clustered around St. Paul’s, a tableau that had endured for a millennium. After the fire, while the cathedral and the churches looked different, the arrangement was largely the same. So, might one conclude that nothing changed? No, because the post-fire rebuilding of London imported onto London’s skyline a new Renaissance ideal that the Dark Ages had little inclination to realise: beauty.

There are some who contend that the current disfigured state of London’s skyline is justified by the fact that unlike Paris or Vienna, it never had much of a skyline to begin with. This gross misunderstanding is easily countered by two historical figures who clearly disagreed. During a visit to William III in 1698 Peter the Great was so mesmerised by how London had been rebuilt after the fire that upon his return to Russia he set about building a new city inspired by what he had seen, St. Petersburg. Today, that city provides a more accurate insight into the historic character of London’s skyline than London itself.

And Canaletto’s stunning mid-eighteenth century watercolours of London from the Thames reveal a city bejewelled with a constellation of church spires clustered around St. Paul’s, a vignette that Renzo Piano claims inspired the form of his Shard. This was essentially the skyline the Great Fire of London bequeathed to the city for the next three hundred years and up until the Second World War, it was an essential part of London’s urban character, form and identity. And tragically, it has all but vanished today.

Style

If there were any two winners from the Great Fire of London then one was Christopher Wren’s career and the other was the baroque. The baroque had begun in late sixteenth century Italy as an artistic counter-reformation exercise by the Catholic Church and as such, it remained total anathema to Protestant England. However, by the 1660s, its ideas had begun to discreetly percolate to these shores. Wren had visited Paris and was aware of the work of Versailles architect Jules Hardouin Mansart as well as Bernini and Michelangelo.

The reconstruction of the city after the Great Fire of London provided the perfect opportunity to import an albeit Anglicised version of the style en masse and this period saw the flowering of a unique English Baroque that was to last for half a century. This age still represents one of the most fruitful, productive and dynamic periods in the entire history of British art and architecture.

With London essentially a blank canvas, the style was applied to new churches, hospitals, livery companies, monuments, townhouses and palaces and its brash ostentation became the defining stylistic template of Restoration London that we still associate with the period to this day. And while Wren was its most prolific exponent he was by no means the only one, the fire and Wren’s success combined to present opportunities for other baroque architects such as Vanbrugh, Hawksmoor, Talman and Archer.

A sudden change in tastes in the early 18th century brought the baroque to an abrupt halt. But that wasn’t the end of the story, when Edwardian England was rooting around for a style that it felt matched the might of empire, it settled on a rebooted neo-baroque style that harked back to a previous period of expansion and came with the requisite amount of drama and ostentation. So if it had not been for the Great Fire of London, there’s a chance we may never had the Old Bailey, Admiralty Arch, County Hall or, even further afield, Liverpool’s Liver Building of today.

Planning

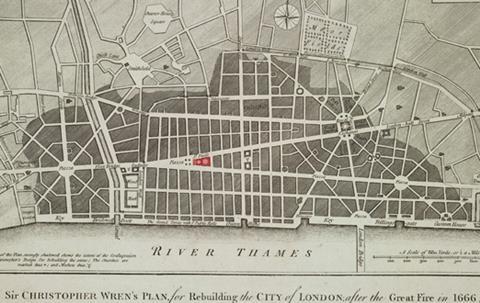

A week after the Great Fire of London Charles II issued a proclamation declaring that the newly rebuilt London was to be “a much more beautiful city than is at this time consumed.” He established a commission to expedite this decree and various architects dutifully presented plans for the city’s reconstruction.

Of course the most famous of these is Wren’s and the king himself was keen to see it realised. But London’s property owners, flexing ancient property rights muscles, were more interested in balance sheets and profit margins than boulevards and vistas and insisted the city be rebuilt as quickly as possible without lengthy recourse to the grandeur that king and architect envisaged.

So as we all know, London was rebuilt largely on the same lines as before subject to the new building regulations implemented after the fire. But while the entirety of Wren’s plan to bring formality and order to the London’s jumbled streetscape was ultimately frustrated, it survived in small but fascinating parts.

One tiny segment of Wren’s plan was built, King Street which links Cheapside to the Guildhall and whose axial symmetry today provides a tantalising glimpse of what else might have been. And to the west, Wren’s Royal Avenue in Chelsea, while part of a later aborted plan to link to Kensington Palace and Chelsea Hospital, still provides a sense of the kind of broad, tree-lined avenues that might have been lining the City today.

However, even though Wren’s plan was never realised, it still lives on today in the new generation of West End squares developed after the Great Fire of London to house the aristocrats rendered homeless by the Great Fire. These have become enduring symbols of London and in the symmetry, order and formality of their original layouts, Bloomsbury, Leicester, Russell, Golden and Soho Squares all bear traces of Wren’s plan.

And even later, implemented schemes by John Nash, Aston Webb and even the London County Council at Kingsway and Aldwych all seek to realise the kind of imperial scale and symmetry Wren had sought to deliver.

But what fascinates in a planning sense is not what wasn’t built but why it wasn’t built. The frustration of Wren’s plans is indicative of a loose and organic planning approach that instinctively rejects the imposition of a formal masterplan in favour of empirical valuations often more sensitive to private interests, an approach that is still in place the City of London today. On one level, this strategy has been responsible for the energy and dynamism of London’s built environment and makes it able to respond much more quickly to social or economic change than its more regulated European counterparts.

But on the other hand it leads to the kind of regressive planning reticence and ineffectuality that has resulted in the mess London’s skyline is in today and leaves its character vulnerable to harmful incursions from poor design and opportunistic development.

Wren’s Monument to the Great Fire of London may be considered the fire’s paramount memorial. But the most eloquent testament to the event is actually inscribed on the Monument’s south panel. For in this short sentence, we see the habitual approach to planning in London that the fire not only failed to eradicate but that still thrives in the city to this day:

“Haste is seen everywhere, London rises again, whether with greater speed or greater magnificence is doubtful, three short years complete that which was considered the work of an age.”

No comments yet