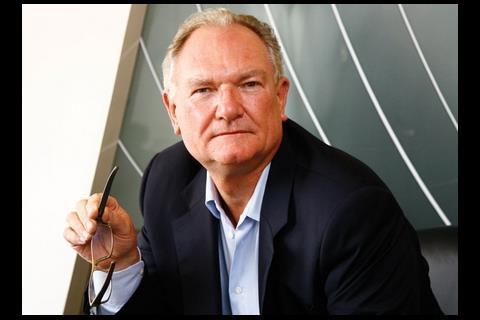

Benoy chairman Graham Cartledge turned a firm that mostly designed Nottinghamshire farm buildings into a £38m global player. Here he talks to Emily Wright about ruthless calculation, creeping mortality and the phone call that changed his life

‘I made a very important decision six years ago,” says Graham Cartledge, with a look of enormous satisfaction on his face. “And that decision is the reason I have the time to sit here and have this conversation. Otherwise I’d be too busy keeping the business alive.”

The chairman of architect Benoy is referring to his decision in 2002 to expand his practice overseas. In the five years since, the group’s turnover has risen £30m.

On top of that, Cartledge was awarded a CBE earlier this year for his contribution to architecture. And as the sole owner of one of the most successful architectural firms in the world, he is a very rich man indeed.

It is hardly surprising, then, that he shows no signs of selling up, despite rumours of approaches. After all, why should he? The future looks sunny.

On this particular afternoon, the wider financial outlook is altogether stormier. Panic over the economic downturn has reached a new intensity as HBOS, Britain’s largest mortgage lender, has just announced that it is in merger talks with Lloyds TSB. Bankers are clearing their desks and the property market is still plummeting.

Cartledge, however, safe in the knowledge that 80% of his business is based abroad, settles down in his boardroom to talk about his car collection (Aston Martin DB9s mainly), how he engineered a management buyout from a phone box in St Tropez and the challenges of breaking into the international market.

The business

In 1973, Cartledge bought Graham Benoy, a small architect’s firm in Newark, that specialised in designing agricultural buildings for Nottinghamshire landowners. The company grew through the seventies and eighties, but Cartledge became frustrated at not being able to elevate it past “third division” status. So, in 1997, he sold it for £4.5m to one of the largest practices of the time, Fitch & Co, and stayed on as managing director.

But Cartledge felt the newly created

Fitch Benoy became dominated by accountants, business plans and a top heavy management with “no understanding of international trading”. In 1992 he decided enough was enough. “I made the call from a phone box on a beach in St Tropez saying I wanted to buy back the company.” He flew back to the UK that day and walked into the boardroom still in his shorts and T-shirt to start the negotiations that resulted in him buying his practice back for just £600,000.

After the buyout I gave all the staff champagne and the next day I sacked half of them and cut everyone else’s salaries by 10%

Cartledge dismisses claims that he has remained sole owner of the company for financial gain. Rather, he argues that it is the only way to ensure clear thinking and quick decision-making, and that is clearly his speciality, even when it requires being the bad guy. “After the buyout we all went out and celebrated. I gave the staff champagne and the next day I sacked half of them

and cut everyone else’s salaries by 10%,” he says. Such is the ruthless business brain whirring away behind the grey hair and wide smile.

Good timing

Cartledge’s decision to expand overseas in 2002 has propelled the group from a small, UK-focused firm to a global powerhouse in just five years. Turnover has soared to almost £40m, from £4.5m in 1992, and the group is well established in 34 countries.

He puts his success down to instinct. “In 2001 I was in a comfort zone and that’s the time to get wary.” Convinced the good times couldn’t roll forever, Cartledge considered his options. “You didn’t need a degree in economics to see that the world order was changing, and that places like India and China were going to be big.”

Identifying potential markets was one thing, but putting the expansion plan into action was another, and Cartledge did not waste any time: “I thought: when better to expand than when I have a good bank account and workload?

So we moved a guy to Hong Kong very quickly. Now we have 200 people out there.”

After the successful move into Hong Kong, Benoy expanded into Arabia and Abu Dhabi in 2004. He has also set up the Benoy Foundation, a charitable trust that is building houses in India and China and helping with the clean-up operation after the Sichuan earthquake. Today the group is looking at opportunities in the Far East, Brazil and North Africa.

Cartledge says research is the key to success abroad. “Methods of doing business will be completely different to the UK. It’s important to know what stage a market is at, how the contracts, payments, tax and government systems work. You need to understand everything from visas to trade.”

He adds that you have to know how to avoid corruption and understand the countless things that constitute doing business: “We make sure we know what the cultural, legislative and financial norms are and work with the British embassy for advice. Do your due diligence and don’t give in to suggestions that manila envelopes are the norm!”

Make sure you know how to do business abroad. Do your due diligence – and don’t give in to suggestions that manila envelopes are the norm

Trust the locals

Cartledge stresses that, where possible, it is best to get local workers involved. Apart from anything else, it saves huge sums of money: “It’s difficult to relinquish power like that in a strange environment but you have to trust the people who know what they’re doing. Having said that, we ask for 10-25% of our fee upfront – just in case. We’ve never put ourselves in the position where we risk doing the work and then get paid nothing.”

Cartledge’s staff work out of one of six hubs including London, Hong Kong, Abu Dhabi and Shanghai. Conference calls and a central computer system join up staff who cannot make face-to-face meetings. “We have 500 people working over 34 countries out of six offices for one company,” he says. “And it works.”

Overseas opportunities

With the UK market contracting, companies are increasingly looking abroad for work. And Cartledge says there is plenty to go around. “It would be arrogant of me to say it’s too late for people to move overseas – it’s not. I’m not denying we got in at a good time because now we are established and respected. But I would see this period as being the second window of opportunity.”

He says there are roles to be snapped up by architects and consultants in particular, but he will not be drawn on exact locations. “I’m not going to say where the opportunities are – we are looking at them ourselves! But what I will say is that in China and India there is a lot going on in terms of schools, PFI and hospitals. So for specialists in those sectors the outlook is good. Those would be good places to start.”

Hands-off approach

Cartledge’s BlackBerry goes off. The interview is overrunning and someone is lurking outside the boardroom to tell him he is late for his next meeting. He looks momentarily stressed but says he can spare another few minutes. His team, he says, can get on with things until he is free – an example of the hands-off management he says is central to Benoy’s success. “When I first took over this group I knew everything about it, and after the buyout in 1992 I tried to keep that up. But I worked myself into the ground.”

By 1996 Cartledge had relinquished a lot of his power: “Respecting the ability of my architects meant that they learned how to manage. The more power I gave to staff, the better the business got. I accept that with 500 people on board, I can’t know everyone’s names or who is good and who is not. Similarly, I can’t know all of our clients – we have more than 500 of them, too. My guys further down the hierarchy know the people in those firms that actually appoint architects. So that’s their job now. There’s nobody left for me to talk to.”

He laughs and follows up with a long pause and a sobering: “Yup. Nobody left to talk to. Everyone I know well is either retired or dead.”

But as so many companies around him crumble in the downturn, Cartledge’s creation is very much alive and well.

Benoy’s rise to global domination

Turnover

2005: £14m 2008: £38m (forecast)

Employees

2005: 182 2008: 500

Staff breakdown

This year Benoy has staff from 30 nationalities working across 34 countries out of six offices

Business breakdown

2000: 80% UK, 20% overseas

2008: 29% Middle East, 25% Asia, 20% Europe, 16% UK, 10% India

Major projects

Yas Island, Abu Dhabi, China World Trade Centre, Beijing

1 Readers' comment