In 1957 Chicago O’Hare International Airport had four runways, today it has eight and by 2020 it will have 10. As Heathrow’s controversial third runway tries to chart a route through the political turbulence ahead, Ike Ijeh looks to see if it has anything to learn from its expanded international rivals

Perhaps only in modern day Britain could it take the government three years and £20m to come to a final decision that isn’t really a final decision because it will take a further six months to “digest” and in any case is exactly the same decision as a previous subsequently reversed final decision definitively decided 12 years ago. Furthermore, were you able to untangle the previous sentence, then you have arguably shown more tenacity and resolve in solving the UK’s aviation capacity crisis than the entire British government.

Last month the Airports Commission convened by the government to investigate how the South-east’s aviation capacity could be increased unanimously and unequivocally recommended that Heathrow should be expanded with a new third runway. While it acknowledged that main rival Gatwick had presented a “feasible” scheme, it concluded that the Heathrow option maximised economic gain and global connectivity and could ameliorate its environmental impact by implementing a number of key mitigation measures.

While Heathrow’s supporters were understandably jubilant, the decision produced an explosive reaction from opponents, a reaction which indicates the ferocity of opposition Heathrow faces on its path towards expansion. The cases for and against are forcefully entrenched. Opponents claim that the environmental impact of a third runway would be intolerable with thousands more suffering from noise pollution, additional pressure on the M25 and M4 motorways, significantly increased carbon emissions and the demolition of hundreds of homes.

On the other hand Heathrow’s supporters claim that its expansion is the only realistic option, pointing out that Heathrow is a globally envied national asset that is already the UK’s only hub airport, is Europe’s busiest airport and the world’s third busiest, enjoys high airline demand, has the strategic connectivity to maximise long-haul routes to emerging markets and will generate 100,000 jobs and £147bn for UK GDP by 2050.

Moreover, as the split-hub option has been conclusively rejected by all parties and Heathrow already operates at 99% capacity, failure to expand the airport would inevitably necessitate a new UK hub somewhere else. As the whole point of a hub airport is that each country only has one of them, this would, in all probability, lead to Heathrow’s closure, which, according to economists such as the London School of Economics’ Professor Tony Travers, would have cataclysmic economic consequences for west London, “similar to the shockwaves experienced in east London when the docks closed”.

While the traumatic gestation of Heathrow’s Terminal 5 proved conclusively that protracted prevarication is a uniquely British response to hyper-controversial infrastructure proposals of this kind, many of the arguments presented for and against Heathrow expansion have been replicated at foreign international airports seeking to expand also.

In the years the UK government has spent dithering over a third runway Heathrow may have lost its coveted and long-held title of world’s busiest airport for international passengers to Dubai. But many other major airports across the world have also struggled to overcome many of the expansion obstacles that Heathrow now faces and could provide useful lessons for and against the embattled west London airport’s plans.

Heathrow Airport

London, England

Opened: 1930

Runways: 2

Terminals: 5

Area: 3,000 acres

Passengers (2014): 73m

Quickest city centre transit:15 min @ £21.50 (20 miles)

Haneda Airport

Tokyo, Japan

Opened: 1931

Runways: 4

Terminals: 3

Area: 4,500 acres

Passengers (2014): 72m

Quickest city centre transit: 15 min @ £2.50 (13 miles)

The world’s fourth busiest airport benefits from a strategic geographical position that could theoretically allow limitless future expansion; unlike landlocked Heathrow it is located beside the sea. In a powerful demonstration of the seaborne expansion opportunities London mayor Boris Johnson claimed would be enjoyed by his vanquished Thames Estuary airport proposals, Haneda’s 2010 expansion made full use of this natural asset by building a new runway entirely on land reclaimed from the sea. Moreover, sea reclamation in Japan does not incur the environmental consternation it would be likely to cause in the UK. With the world’s fifth longest coastline, more than 0.5% of Japan’s total area is reclaimed land and it is a practice that has been embedded into Japan’s physical and cultural fabric since the 12th century. In stark contrast to Heathrow’s development paralysis, Haneda’s 2010 expansion was a model of Japanese technological and organisational efficiency. Already recognised as the world’s most punctual airport, Haneda added a runway and terminal inventively financed by a mixture of PFI, duty free concessions and a moderately controversial passenger development tax. As well as this, both the Tokyo Monorail and the local airport transit line were extended to serve the new terminal. Further expansion plans, including yet another railway link, are under way in preparation for the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games. Haneda also benefits from an operational advantage that would be unthinkable at Heathrow; it is open for flights 24 hours a day. This has come with problems with local residents’ noise complaints spiralling since the new runway opened. The problem has been partially and pragmatically abated by airliners now being required to fly at a minimum altitude of 6,000ft over Tokyo – planes serving Heathrow can typically fly well below half that distance. Haneda expansion is also restricted by another constraint thankfully not present at Heathrow: it is lodged between the flight paths of a nearby military base and airport and is consequently forced to observe severe airspace and scheduling restrictions that compromise its operational efficiency.

Schipol Airport

Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Opened: 1916

Runways: 6

Terminals: 1

Area: 7,000 acres

Passengers (2014): 55m

Quickest city centre transit: 20mins @ £2.80 (11 miles)

“Every time someone in the British government says ‘no’ to a third runway, Schiphol boss Jos Nijhuis thanks me.” So spoke former Heathrow executive Colin Matthews of his smarting Dutch equivalent. Nijhuis has form for riling his Heathrow rivals – in 2012 he jokingly offered Schipol’s planned seventh runway as a stand-in for Heathrow’s stalled third. Incredibly, if Schipol gets its seventh runway, then it will have the same runway capacity as London’ six airports combined. Moreover, there is some basis to Nijhuis’s bluster as bizarrely, Schipol provides more long-haul transfers for UK regional passengers than Heathrow. But Schipol too has had its share of expansion planning battles. Its newest runway opened in 2003 but development was delayed by almost a decade due to fierce environmental protests. Its construction was also agreed only after a series of environmental concessions, including severe restrictions on operating times and its location being moved to a position that requires a hefty 15-minute aircraft taxi from landing to terminal. But, while Schipol may share some of the political and environmental obstacles that Heathrow does, it does not share the physical ones, as KLM chief executive Pieter Elbers recently observed. Although extensive housing is located within yards of the airport, it is also surrounded by acres of open and uninhabited flatland which could relatively easily be deployed for future expansion.

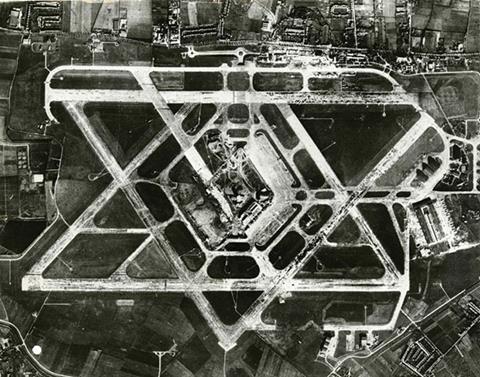

O’Hare International Airport

Chicago, USA

Opened: 1943

Runways: 8

Terminals: 4

Area: 7,700 acres

Passengers (2014): 70m

Quickest city centre transit: 40 mins @ £1.45 (15 miles)

Many opposed to any expansion of London aviation capacity point out that while Heathrow might be straining at the seams, London’s six international airports benefit from a total of seven runways and constitute the largest city aviation system in the world. While this argument may appear statistically seductive, it’s rather like expecting a stranded motorist who has run out of fuel to take comfort from the fact that there are five petrol stations located nearby, even if they are all closed. Moreover, it also ignores the experience of the city whose principal airport has the most runways in the world, Chicago. Even with a record-breaking eight runways, the world’s busiest airport for total cargo and passenger traffic is still crippled by queues, delays, multiple cancellations and acute scheduling congestion, inconveniences that have a ripple effect across North America due to O’Hare’s hub status. The problem with O’Hare is essentially one of layout and logistics rather than space; unlike Heathrow, the airport has more than enough capacity to meet current demand. But despite covering a site area well over twice the size of Heathrow’s, it is hampered by poor infrastructure and connectivity and a disparate assortment of cramped and outdated buildings and facilities.

As a result the airport has embarked on a colossal £9bn expansion and modernisation programme, the first phase of which culminated in the opening of its newest runway in 2013. More runways, infrastructure and a new control tower and terminal are planned by 2020 but the plans are dogged by Heathrow levels of opposition and have been intensely criticised for providing unneeded additional capacity while failing to address O’Hare’s chronic logistical flaws. A litany of lawsuits from airlines and residents accompanied phase one which involved the relocation of 2,800 people and 1,400 graves from a neighbouring county. Subsequent phases are equally beset by extreme resident and environmental opposition, much of which focuses on the incendiary issue of noise (like Heathrow, O’Hare has military origins and is hemmed into a suburban residential district). The airport has recently responded to noise concerns with a 15-point noise abatement and mitigation plan and opened the possibility of revising proposed runway layouts to ensure that planes take off over less residential areas at night. But it is far from assured whether this will be sufficient to quell opposition. But while Heathrow and O’Hare may face similar development problems, O’Hare has one indisputable advantage over its English counterpart. It is entirely publicly owned by the City of Chicago and therefore has its fate determined by a planning authority unequivocally committed to its growth.

Frankfurt Airport

Frankfurt, Germany

Opened: 1936

Runways: 4

Terminals: 3

Area: 5,000

Passengers (2014): 60m

Quickest city centre transit:15 mins @ £3.00 (10 miles)

The one European hub airport that can probably identify most with Heathrow’s expansion trauma is Frankfurt. If Heathrow thinks its troubles will be over by the time its third runway is built, it can think again. In bravado displays of organised Teutonic pique, thousands of campaigners regularly and noisily besieged the airport after the completion of its newest runway in 2011 to mount mass impromptu renditions of Silent Night to satirically underline their annoyance at the alleged noise contraventions expansion had produced. Germany’s biggest airport’s fourth runway only opened after a bruising battle with local residents and environmental campaigners. A key legal confrontation concerned the new runway’s night-time ban, similar to that already operated at Heathrow. While this had been assured during construction, once complete airport authorities appeared to be making moves to reverse it, a development that enraged opponents and was only quashed after the ban was upheld in court. The airport’s CEO bitterly claimed the ruling was “good for London, Paris, Amsterdam and Dubai”. Unrepentant, the airport is pursuing further expansion plans with construction starting on a new terminal this year (above) and completion expected by 2021, again in the face of fierce opposition. However, noise appears to be Frankfurt’s chief obstacle, while the physical and political constraints that hinder Heathrow expansion do not apply. Although there are residential areas nearby, Frankfurt is primarily surrounded by forests and can even rely on the changing geopolitical landscape to assist its growth – its new terminal will be located on an adjacent former US airbase.

Charles de Gaulle Airport

Paris, France

Opened: 1966

Runways: 4

Terminals: 3

Area: 8,000 acres

Passengers (2014): 64m

Quickest city centre transit:25 min @ £7.00 (18 miles)

Unlike the majority of Heathrow’s neighbours, there are some who live near Charles de Gaulle who could actually claim to have moved there before the airport. Not that residential proximity is a big impediment to Charles de Gaulle’s operations; surrounded by rolling acres of open, uninhabited brown and greenfield land, it is one of the world’s biggest airport sites and was specifically situated in a sparsely populated, semi-industrial region of a Parisian suburb in order to accommodate the future expansion capacity that has so thwarted Heathrow. Moreover, while its roughly 16 mile distance from the centre of Paris is approximately the same as Heathrow’s distance from central London, the fact that Paris is a much smaller city means that the airport’s flight paths are located over significantly less densely populated areas. So the relative youth of Heathrow’s closest European rival means that it benefits from the kind of modern urban and aviation planning that Heathrow’s pre-war inception plainly lacked. In many ways therefore, Charles de Gaulle remains a model for modern, urban airport development. Accordingly, after its inauguration the airport has enjoyed steady and relatively uncontested runway openings in 1981, 1988 and 2000 and while there are no current plans for major expansion, usurping Heathrow’s primacy remains an overriding ambition and, unlike Heathrow, future growth can be easily accommodated. This is not to say that expansion plans have been entirely without trouble; tragically, the roof of the new Terminal 2E collapsed in 2004 killing four people.

No comments yet