The industry needs some clarity on carbon reduction targets. Building looks at three examples of low and zero-carbon housing

In 2006, the Labour government gave the housebuilding industry 10 years’ notice to make its products zero-carbon. This ambitious requirement was launched as part of the Code for Sustainable Homes, and included interim carbon reduction targets along the way: 25% reduction in emissions in 2010 and 44% in 2013. Zero-carbon was going to be expensive - adding up to £40,000 per home - but the argument was that the industry would find ways of reducing these costs as the 2016 deadline approached.

About the only aspect of the zero-carbon requirement welcomed by the industry were the clear carbon reduction milestones along the way. This gave manufacturers confidence to invest in zero-carbon-friendly products and galvanised housebuilders into action. A collection of odd-looking homes sprung up at BRE’s innovation park at Garston, near Watford. Zero-carbon made the industry innovate.

That confidence has taken a battering since the last election. The chancellor George Osborne changed the definition of zero-carbon in the March 2011 Budget so housebuilders would no longer have to provide zero-carbon energy for domestic appliances, just heating, fixed lighting and hot water. Confidence has been further undermined by cuts in feed-in tariff rates for renewable technologies.

The biggest wobble, however, came from the 2013 Part L consultation. Instead of the 25% cut in carbon emissions over 2010 as proposed in the Code for Sustainable Homes, the government favoured an 8% cut, citing the election pledge not to place additional burdens on housebuilders during this parliament. This means that housebuilders face a much bigger jump in 2016 to keep the zero-carbon deadline on track. Additionally, the details of allowable solutions, the mechanism for handling how carbon emissions are mitigated off site, has yet to be finalised. The Zero Carbon Hub put forward proposals for managing this process in July 2011 but the government has yet to respond.

The carbon reduction jump needed in 2016 to keep the zero-carbon policy on track may be too big for the housebuilding industry to cope with. This means the date could be shifted to 2019, which would align with the date for all other buildings to be zero-carbon. Either way, the industry wants to know now. “We do need clarity now,” says Dr Elizabeth Ness, group sustainability director at Crest Nicholson. “We are hoping that, whatever is in the 2013 regulations, it will also give us a future trajectory, as uncertainty is very bad. It doesn’t let us plan properly when it comes to buying land and it is bad for supply chains as they need certainty to invest.”

The government is watering down the zero-carbon targets for cost reasons. According to figures from the communities department, building a three-bedroom semi on a brownfield site would cost 4% extra if carbon emissions were cut by 25% over 2010 Part L and 15% extra to meet the new definition of zero-carbon. Meeting the target set to the original definition of zero-carbon would cost an extra 29%. But some housebuilders and designers have developed low and zero-carbon solutions that cost very little more than a home built to Building Regulations.

This demonstrated that zero-carbon homes are financially viable and makes the case for the government to press on with the zero-carbon agenda. The industry needs a clear deadline for all new homes to be zero-carbon, plus interim targets and workable solutions. Whether this is by 2016 or later, the government needs to bring clarity to the table now.

Zero Bills

Architect Bill Dunster could be considered the father of zero-carbon. He designed the UK’s first zero-carbon development, BedZED, which completed in 2002, long before the introduction of the Code for Sustainable Homes. Dunster’s firm, ZEDfactory, has been developing and refining the concept ever since.

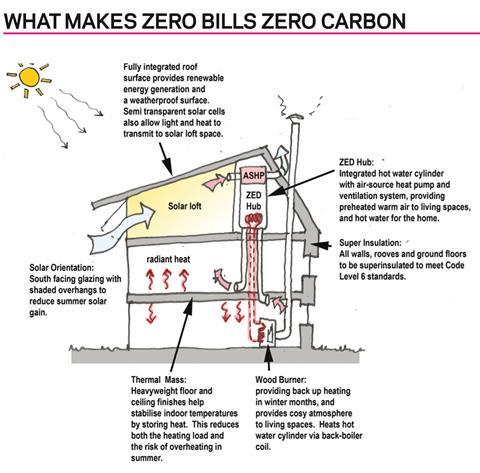

This has given him plenty of time to cut the costs of a zero-carbon home to a minimum. The latest incarnation is called Zero Bills and will be launched at the Ecobuild event in March. These homes align with the original definition of zero-carbon, as all the power needed for appliances is generated on site. The “zero bills” concept is a financing mechanism combined with low build costs. “The payments leaving your account are the same as paying the mortgage on a Building Regulations home and paying energy bills,” explains Dunster. He adds that the Ecology Building Society will underwrite the more expensive loans needed for a Zero Bills home.

A five-bedroom, detached home costs £19,000 more than a Building Regulations home. This is much less than the £31,180 the government calculates it would cost for a four-bedroom, detached home. The key to the concept is the roof. Developed as a joint venture with Chinese PV manufacturer Himin, the roof consists of PV modules integrated into glazing. These are installed over a timber frame with the PV modules joined by a specially designed and made drainage and sealing detail.

The combination of low manufacturing costs in China and the fact that the modules double up as the roof cladding keeps costs down to £150/m2. “You would struggle to get a slate roof for that,” says Dunster.

The roof generates up to 8kWp which is more than enough for the home’s energy needs. The financial model relies on feed-in tariff payments but Dunster says the fuel price escalator means energy prices will increase to a point in two years’ time when the feed-in tariff payment will no longer be needed to make the finances stack up.

A hallmark of ZED is a sunroom, which harnesses solar gain to keep the house warm. The glass roof of a Zero Bills home turns the roofspace into a conservatory, which is used to harness solar gain. An air source heat pump with a 700W output concentrates this heat, which is distributed around the home and provides water heating. Heat demand is low as the homes are insulated to the equivalent of Passivhaus standards. Terracotta blocks are incorporated into the ceilings to add thermal mass.

Dunster says the Zero Bills concept doesn’t mean UK jobs disappearing to China. The homes can be made by UK-based timber framed manufacturers. Zero Bills will be available as a kit of parts, and ZEDfactory is developing the concept directly with landowners and local authorities. Outline planning has been granted for a 91-home Zero Bills scheme near Plymouth in Devon, which demonstrates that zero-carbon is alive and kicking.

COSTS FOR ZERO BILLS

Indicative build costs

For a five-bedroom detached house with a gross floor area (GFA) of 141m2 near Plymouth (excludes fees):

- Cost of building a timber framed home to 2010 Part L £141,000 or £1,000/m2

- Cost of ZEDfactory timber framed home built to comply with the 2016 definition of zero-carbon £157,000 or £1,115/m2

- Cost of Zero Bills home including sufficient PV to supply all regulated and unregulated energy requirements, £160,000 total, or £1,135/m2

Running costs

- Home to 2010 Part L: £960/year for gas and electricity

- Home to 2016 definition of zero-carbon: £276/year for electricity (no gas needed)

- Zero Bills home: no annual bills and savings cover interest on additional £19,000 capital cost of home. Also receives income of £965 a year from feed-in tariff

Beattie Passive and One Brighton

Pete Halsall is another zero-carbon veteran with roots dating back to BedZED. He was behind the “highly profitable” zero-carbon One Brighton scheme and is now chief executive of Beattie Passive. This is a standardised kit of parts that is used to build homes to Passivhaus standards. “It delivers Passivhaus performance at normal build costs,” says Halsall. The jump from Passivhaus to zero-carbon is relatively small - £5,423 for a three-bedroom semi-detached home - as the main energy requirement is hot water and fixed lighting, as a Passivhaus needs virtually no heating.

Created by former carpenter Ron Beattie, the system is designed to be foolproof. It consists of just 16 standardised components. According to Beattie, these can be put up by anyone “who can hold a hammer”. The frame is based around a series of space studs, configured to minimise the number of air and heat losing interfaces. Beattie Passive tests each for air leakage and acoustic and thermal performance, and, if they meet required standards, issues Passivhaus certification.

According to Halsall, the key to keeping costs down is standardisation with build simplicity. “We need a standardised system that can be built by semi-skilled carpenters,” he says. Beattie Passive used 18-24 year olds who were third-generation unemployed to build four Passivhauses in Scotland. These exceeded the Passivhaus requirements by a wide margin. “Sustainability is about solving the climate change issue and getting people into work,” Halsall says. “There is something like a million unemployed 18-24 year-olds [in the UK], which is an absolute disgrace. This system allows those people to come into the industry.” Halsall wants to license the system to anyone who is interested in using it and also do some developing.

Halsall also managed to deliver the zero-carbon development One Brighton at market prices and still make a healthy profit. Developer Bioregional Quintain negotiated with the planners to increase density, which increased profitability. It cut out the basement level car-park, saving £2m. Halsall says build costs were kept to just 3% more than a standard development. “We tried to keep things as simple as possible to keep the costs down,” he explains. The concrete frame utilised post-tensioned slabs, which reduced the amount of concrete needed. It was made from concrete containing 50% cement substitute and 100% aggregate, which was green and saved money.

BEATTIE PASSIVE

Indicative build costs

For a three-bedroom semi-detached house in Dunfermline, Scotland, with a GFA of 86m2 (excludes fees):

- Cost of traditionally constructed standard home to 2010 Part L, £93,975 total, or £1,092.73/m2

- Cost of Beattie Passive home with Passivhaus certification, £93,898 total, or £1,091.83/m2

- Cost of Beattie Passive home with Passivhaus certification built to comply with the 2016 definition of zero-carbon, £99,398 total, or £1,155.79/m2

AIMC4

AIMC4 is a consortium of Crest Nicholson, Barratt and Stuart Milne that has set itself the simple objective of building code level 4 homes at code level 3 prices. The consortium is trialling different build methods including timber frame and the H+H Celcon aircrete block system. Dr Elizabeth Ness, group sustainability director at Crest Nicholson, says the 2016 target was the driver for this initiative. “We know where we have to get to and have this trajectory, which is good,” she says.

The approach has been to create a highly insulated envelope and drive cost out of the build process. “The objective is to partner with our suppliers to develop solutions that work technically and cost effectively, which also have the ability to engineer cost out over time,” she says. One example is windows - rather than getting frames, panes and seals separately, Crest worked with its suppliers to develop this into a combined system that could be adapted for different developments.

Homes are highly insulated, including triple glazing, and fitted with energy-efficient LED lighting and ventilation systems. The consortium is also trialling new technologies including dynamic insulation, which reduces wall thickness for the same level of thermal performance. Ness says the consortium is making progress and hopes to hit the AimC4 objective by 2014.

She concedes volume sales will be the key as this brings economies of scale that are difficult in the current market. The homes will be monitored to check performance and the results disseminated to the rest of the industry.

To learn more about our Green for Green campaign aims, click here

3 Readers' comments