A ring-fenced retrofit programme for public buildings would boost the economy, cut carbon emissions, and even pay for itself. So why isn’t it happening?

According to the Carbon Trust, central and local government buildings contribute up to 3.4% of the UK’s carbon emissions. So if the government is going to meet its ambition of being “the greenest ever” - and have a hope of honouring its commitment to reduce its carbon emissions by 34% by 2020 and 80% by 2050 - it will clearly have to tackle this area of urban sustainability.

In fact when it comes to its own property, the public sector in England is pretty demanding on sustainability standards. For example, central government projects must achieve a BREEAM “excellent” and major refurbishments must achieve a “very good” rating; the same standards apply to healthcare projects. Schools have to achieve a “very good” rating or equivalent and social housing must meet level 3 of the Code for Sustainable Homes. Most public sector projects will be built to meet these minimum standards but some organisations exceed them as a result of locally set planning rules.

“To be fair to the government, it does make demands for its new buildings and has started to do the same for refurbishments,” says Nick Hayes, head of sustainability at EC Harris. “It’s acting as a market driver in that if you want to develop buildings that the public sector is going to occupy, then you’ve got to deliver them to a certain standard.”

So, the policy is pretty sound, but unfortunately there is no programme in place to ensure that all those drafty town halls get the attention they need. What’s more, there are huge numbers of public buildings that probably don’t need a major refurbishment, but could make significant reductions in energy consumption (and cost) through smaller interventions such as better insulation and lighting controls.

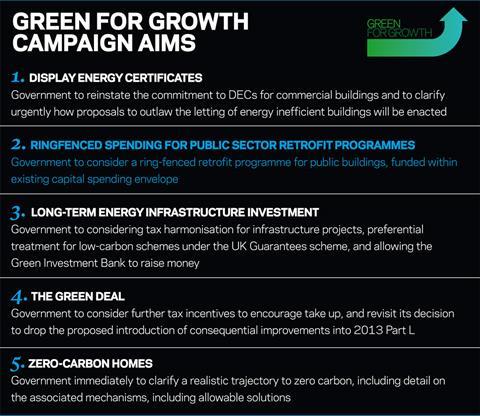

It is for this reason that at the beginning of the year Building called on the government to consider a ring-fenced retrofit programme for public buildings as part of our Green for Growth campaign. Our proposal is that the programme could be funded by a combination of the £1.5bn annual government departmental under-spend and bringing forward spending from later on in the parliament.

The pay back

Notwithstanding the coalition’s focus on deficit reduction, spending on a retrofit programme for public buildings would be a genuine investment; ultimately paying for itself by reducing utilities costs for public bodies. “It’s a sensible way for the state to spend money because ultimately it reduces the consumption of energy across an estate and then it’s an invest-to-save model,” says Alan Somerville, director of strategic solutions at Capita. “The payback period depends on what you’re dealing with. Simple interventions can be pretty quick - from a matter of months, onwards.”

Somerville’s experience is backed by evidence from Salix Finance, a not-for-profit company funded by the communities department and the Welsh and Scottish governments. Salix provides interest-free loans (or match funding for recyclable funds) to public bodies that want to invest in energy-saving technologies but don’t have access to sufficient capital to fund the initial investment. According to the company, on average Salix projects pay for themselves within three and a half years and have a lifespan of 13 years before equipment needs replacing, providing nine and a half years of energy savings at no cost. To date, the company reports that it has funded over 9,000 projects with 662 public sector bodies, valued at £194m, saving the public sector £56m annually and £750m over project lifetimes.

While few projects, be they new build or refurbishments, are ever completely shovel ready, investments in energy efficiency works also have the benefit that they can be made quickly. Somerville, however, sounds a note of caution. “The key is making sure that you do enough analysis up front - a piece of work that allows you to accurately assess what your options are, what the upfront investment will be and what the return on investment will be,” he says. “It doesn’t have to take a huge amount of time, but historically some organisations have done a little bit here and a little bit there. There hasn’t necessarily been much co-ordination. You need to bring things together.”

Of course, building works alone won’t be enough. In order for a retrofit programme to be truly effective it would have to accompanied by a campaign to raise awareness on energy efficiency among people who occupy the buildings. “You can retrofit buildings as much as you like, but if people in the buildings work in a deeply inefficient way, much of the retrofit benefit will be lost,” says Pascal Mittermaier, head of sustainability at developer Lend Lease.

According to Paul Dunn, head of sustainability at law firm Eversheds, which is currently in the midst of a substantial retrofit and refurbishment programme, the process of investing in sustainability can help change the culture of an organisation. “The assets of a building need investment,” he says. “That investment will result in lower running costs. But it will also result in a more environmentally conscious organisation.”

In the age of austerity, you’d better have a good argument to make if you want to persuade the government to push more of its limited resources in your direction.

Our call for a ring-fenced retrofit programme for public buildings is just that: a compelling argument.

The programme would pay for itself in the medium term, would contribute substantially towards the government’s own target to cut carbon emissions 80% by 2050 and would provide a boost for the construction industry. It would also mean that the state was leading by example and could potentially begin to ask more of the private sector in sustainability terms. What’s not to like?

For more on the campaign aims, click here

To read our feature on display energy certificates, click here

Ahead of the curve

Bristol council is investing in energy-saving measures and beginning to see the rewards:

Bristol council has taken an interest in energy efficiency and renewable energy for 15 years and has a target to reduce energy use against projected levels by 20% by improving efficiency, increasing its use of renewable energy to 20% of its total annual consumption, and reducing its emissions of greenhouse gas by 20%. The authority calls the set of policies its 20-20-20 targets.

The council has a £1.2m fund that it uses to invest in energy-efficiency projects, with the savings generated from those projects going back into the fund. The fund was set up in partnership with Salix, a not-for-profit company funded by the Department of Energy and Climate Change. According to the council, the programme of work that the fund has financed delivers annual savings of £800,000 and 4,450 tonnes of carbon.

Bristol is now investing in solar energy on council-owned buildings and schools; a project it says is the largest of its kind in the UK. Ultimately, the council believes that the initiative will save it £60,000 and generate income from the feed-in tariffs (FITs) of about £100,000 each year for 25 years, presuming that the government’s policy on FITs doesn’t change again. It says that the PVs will cover an area the size of 15 tennis courts and save around 280 tonnes of carbon each year.

In addition, there are plans to construct two wind turbines with a capacity of 3MW each in Avonmouth. Tenders are being negotiated for the supply, installation, operation and maintenance of the turbines. Planning permission was granted in 2009.

No comments yet