BIM is central to the success of Gatwick airport’s massive £1.2bn capital investment programme. But with integration key, how can BIM bring maximum benefits when parts of the supply chain just don’t get it?

While the recent Airports Commission report has apparently stalled any imminent expansion, Gatwick airport remains the busiest single runway airport in the world and the second busiest airport in the UK, after Heathrow. Close to 40 million passengers used Gatwick last year and its two terminals measure almost 3 million square feet and are spread across a vast 8ha estate.

Managing an infrastructure facility of this size is a mammoth undertaking at any time but Gatwick is currently undergoing a £1.2bn capital investment programme – the biggest in its history – which has prompted a comprehensive and ongoing overhaul of its entire construction, maintenance and facilities management operations.

Central to this project is the wholesale adoption of BIM technology. HOK, as architect in charge of delivering Gatwick’s development framework, has been integral in establishing the BIM system on which the framework has been based. Rod Hulse, Gatwick’s head of development engineering explains: “BIM offers us the opportunity to develop a huge programme of improvements to Gatwick airport […] without creating a massive disruption to our operation and while allowing us to integrate all our projects together and see where the interfaces are – and still deliver world class facilities for our customers.”

In design terms, Hulse defines the BIM vision at Gatwick as one that delivers a number of targets, all of which are based around a crucial process: integration. “Integration is key. Integration between designers, contractor and operators in order to extend data life cycles and provide data more quickly, accurately and efficiently. This data can then be analysed and fed back to inform other ongoing projects and refurbishments.”

Hulse points out that the level of integration and information BIM provides is also critical from a facilities management perspective. “Integration is essential and from a facilities management point of view, it’s essential that maintenance information is available right from the start. This will enable us to determine what is the best equipment to use in order to minimise cost.”

This acute level of scrutiny of BIM’s data rather than modelling capabilities also indicates a key ideological position the Gatwick team hold with regard to BIM. As Gatwick BIM manager Julian Jameson explains, for them BIM has a much richer potential than purely 3D modelling. “Some people within the industry are still obsessed with looking at BIM purely as a 3D modelling tool. We see it far more as information management and asset information; it provides a much richer picture of the data and information at hand.”

The “assets” Jameson refers to range from the fabric of the buildings which constitute the airport to the vast infrastructure of mechanical apparatus that serves them. As Hulse points out, “managing these assets within an office environment is likely to be fairly straightforward but managing them on a site with the scale and complexity of an airport presents an entirely different and hugely challenging scenario.”

Although the capital investment programme is ongoing, to date Gatwick can already cite several projects that have benefited from the airport’s evolving BIM framework and each one demonstrates the particular complexity that managing an airport encompasses.

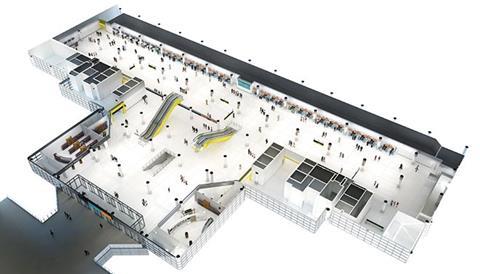

One of the largest is the refurbishment of the North Terminal where new shops and mechanical services such as air handling systems are being installed while the terminal remains fully operational. One of the most complicated ongoing projects has been the overhaul of the baggage handling facilities where the physical build has been forensically co-ordinated with 3D modelling and data information.

Other projects have involved the refurbishment of several airside piers, sometimes requiring the demolition and rebuilding of structures up to 20 years old or presenting the complex engineering challenge of integrating new structure or facilities into existing fabric. All these projects were developed with close reference to an overall 3D massing master model of the airport.

A further level of complexity was added when two particular projects, the renovation of strategic administrative airport properties, Jubilee House and the Airport Operations Building, also required their individual 3D models to be “reverse engineered” to ensure compliance with the 3D massing master model.

While Hulse maintains that quantifying the precise benefits of the BIM strategy is “tricky because it requires analysis of the whole life cycle of a project which may not yet be evident, the Gatwick team are still quick to cite many of the advantages they feel BIM has added to the airport works programme. Many of these are the familiar benefits commonly associated with BIM. Speed, certainty, accuracy, efficiency and co-ordination are identified as well as the economic benefit of being able to quantify a construction budget upfront at project, design or even concept stage.

However, perhaps surprisingly, Hulse is also brutally honest about the challenges and limitations of the BIM process and much of these are centred on one area in particular, the supply chain. “BIM is only as effective as the supply chain and the supply chain, especially the subcontractor supply chain, isn’t quite clever enough yet. The commonality of purpose required to fully utilise BIM is sometimes lacking and there’s also a large variation of knowledge and maturity among contractors and manufacturers which often means that BIM is being pushed down from the client or operator level rather than the other way round.”

Hulse provides an example. “For instance, with tendering teams it’s often obvious who ‘gets’ BIM and who doesn’t. Those with their own manufacturing facilities are often far keener to use it rather than those relying on the supply chain.”

The theme of supply chain adaptability is also one enthusiastically pursued by Jameson. “There are still significant cultural challenges regarding adoptability – it very much depends on individuals. Some of the traditional industry reluctance for different parties to do things together has also migrated from pre-BIM days too – the foundations are there but there isn’t always the collaborative transfer of information we’d like. When that’s the case, BIM is like being given a car without wheels.”

Jameson too provides his own example. “When coming to work on a new phase of refurbishment projects, we often get complaints from contractors about the quality of as-built information from the last phase which might have been completed several years ago. But this information was often provided by the same contractor who at the time was unwilling or unable to provide the amount of information required. There is still this disconnect between fabrication and installation and there is still a big problem with the ‘it’s not my responsibility’ syndrome.”

One area where this “disconnect” appears to be particularly prevalent is with facilities management. Gatwick has ambitious plans here and has set itself the mammoth task of aiming to place facilities management information for the entire airport on to BIM. As is to be expected the venture is one of enormous complexity and the team readily admit to being “far from there” yet. Jameson describes the sheer amount of services and consequently information data related to even a standard baggage facility as “frightening”.

According to Hulse, one of the key challenges with the BIM programme for facilities management is, once again, integration and coordination between different teams. “The trick is better understanding between the facilities managers and contractors, it’s all about anticipating what you can do and what you will need in the future. There’s still a large amount of training to do and we need a more integrated platform that allows for the smooth internal transfer and migration of manufacturers’ information and specifications to the end user.”

Despite the challenges, the Gatwick team remain optimistic about the gigantic task at hand and are determined to fully optimise BIM’s potential for the more efficient management of the airport. Intriguingly, although an infrastructure operation of Gatwick’s size offers few UK equivalents from which they can learn and interact, as Hulse explains there are other facilities they have worked with which have set themselves similar BIM challenges, one of which may come as a surprise to some.

“We’ve looked at a few international precedents and in the UK, organisations such as Transport for London incorporate a similar level of logistical complexity. We’ve looked at Crossrail and it will be particularly interesting to see how their facilities management arrangements carry over from construction to operation.”

“And yes,” he adds, “We’ve even worked on this with Heathrow.”

No comments yet