The chief executive of one of the UK’s largest planning consultants speaks to Tom Lowe about the implications of Labour’s final revisions to the National Planning Policy Framework and what needs to be done to achieve 1.5 million homes by the end of this parliament

Some people find their workloads winding down as the festive break approaches. For others, like Stephen Bell, it is the busiest time of year.

When he talked to Building, the chief executive of £30m turnover planning consultant Turley was immersed in the pre-Christmas rush which swamps the planning sector each December as clients push to get their applications submitted before the big day. This happens despite the fact that council planning officers are unlikely to have looked at them before the new year.

“It’s always the way,” he says wearily. “It must go in before the end of the year. Even though it doesn’t go anywhere”.

But Bell still found reasons to feel festive this year, not least because of the publication of Labour’s final revisions to the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF). While updates to the government’s land-use policy might not seem like the most obvious cause for Christmas cheer, it got the sherry glasses clinking at Turley.

The document is the key lever being pulled by ministers in the hope of enabling a series of ambitious targets, including building 1.5 million homes by the end of this parliament and decarbonising the UK grid by 2030. If it works, Turley and the rest of the planning sector could be looking at some even busier yuletides in the years to come.

This is not to say that Bell does not have some lingering concerns about what the document contains, but the very fact that it appeared before the new year was a “huge, huge positive”, he says. Many in the sector had worried that the revisions, first announced in a consultation launched in July, would be delayed until 2025 or watered down. In fact, some of the more controversial proposals have been strengthened.

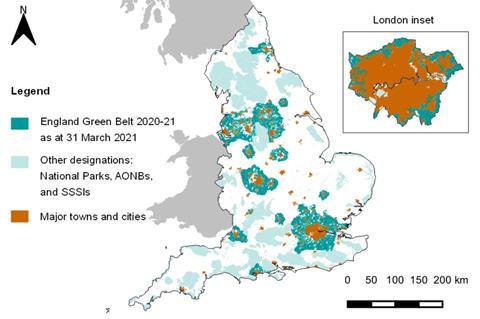

A case in point is the definition of the “grey belt”, a new land class which can be broadly understood as sites in the green belt which do little to contribute to the protection of the countryside. The government’s proposals to allow development on these sites constitute what Bell describes as the biggest change in green belt policy since it was introduced in 1955 to prevent urban sprawl.

The aim is to free up new sites to make it easier for developers to build more homes, although, unsurprisingly, it is also the policy in the new NPPF which has provoked the most opposition from campaigners.

Angela Rayner was ready with a punchy statement when the document was published on 12 December. The secretary of state for housing, communities and local government said the changes would “shake up a broken planning system which caves into the blockers and obstructs the builders,” adding: “I will not hesitate to do what it takes to build 1.5 million new homes over five years and deliver the biggest boost in social and affordable housebuilding in a generation.”

Her language could be read as a preemptive defence for the fact, following calls from the planning and development sectors, during the consultation, the new grey belt policy had gone further than the already controversial definition originally suggested.

In July, the draft document proposed defining grey belt as green belt land that made a “limited contribution” to the five green belt purposes. These can be summarised as preventing urban sprawl, preventing towns merging into one another, safeguarding the countryside from encroachment, preserving the setting of historic towns and encouraging the use of derelict urban land.

>> See also: Updated National Planning Policy Framework explained

The final document has significantly broadened this definition, changing the wording to land that “does not strongly contribute” to just three of the green belt purposes. The purposes removed are encouraging development on urban land, and, more significantly, safeguarding the countryside from encroachment.

Although councils do not always use the same language to define green belt sites – some using a scale from “limited contribution” to “major contribution” and others using different words – the new grey belt definition suggests that any site which is below the top tier of contributions to the green belt could qualify as land suitable for development.

“My reading of that, and I’m sure a few others have reached the same conclusion, is that that is a lowering of the bar,” Bell says. “The language that they’ve now adopted actually makes it more permissive.

“I would say that, as a consequence of the changes, there is likely to be more grey belt proposals than there might even have been under the consultation version.”

The removal of the purpose of preventing encroachment into the countryside also means that a site could make a “strong” contribution to this end but still be classed as grey belt. This appears to have come about because of concerns raised during the consultation that the concept of “encroachment” could naturally be applied to any site in the green belt.

The number of grey belt sites coming forward for development could be significantly reduced by local authorities having the ability to argue that a site was making more than a limited contribution to safeguarding the countryside. Now, that lever has been taken away.

“That’s a big step forward,” Bell says. “The fact that they’ve now tweaked it – and I would say, lowered the bar and removed that purpose – makes it more likely there’ll be more grey belt sites coming forward.”

Meanwhile, the green belt purposes which have been retained in the definition have been significantly weakened in the test needed to categorise land as grey belt, because any opposition to a scheme would need to prove that a site made a “strong” contribution.

More on Labour’s NPPF changes:

Updated National Planning Policy Framework explained

The new NPPF: the time for waiting is over

Grey belt housing delivery will be ‘meaningful but not significant’, says minister

The finalised National Planning Policy Framework: round-up of sector reaction

NPPF: Government drops 50% affordable housing requirement for grey belt sites

Housebuilders and planners welcome Rayner’s plan to bypass local committees on development decisions

Grey belt, green belt and the curious case of Labour’s benchmark land value

NPPF consultation responses show widespread support for proposed changes

Rayner’s ‘new homes accelerator’ is the right kind of big thinking to speed up housing delivery

There is still a degree of uncertainty over exactly what this means because there are no nationally accepted terms for these definitions. The government has said it will publish guidance on how to undertake green belt assessments in the new year in an effort to bring about a greater consistency in language. Either way, the government has clearly set out its direction of travel.

Another major change is the requirement for affordable housing, one of the so-called “golden rules” for building on grey belt sites. Originally proposed as a flat 50% in the draft proposals, the final document has reduced this to 15% above local housing policy, capped at 50%.

This might not make much of a difference for grey belt sites in London, where affordable housing requirements are typically 35% of homes built, but could go a long way to making more schemes viable in parts of the country with lower rates.

“That’s something that we, and I believe many in the development industry were pushing for,” Bell says. “Because it didn’t really recognise the differences across the country about what’s viable to deliver, or indeed, I suppose, the need per se within those areas as well.”

He believes the new approach is a step towards making the policy “more locally nuanced and locally reflective of both viability and need”.

Bell had argued for 10% when Building spoke to him previously, before the publication of the final document, and says the 15% rate will still “inevitably cause some challenges” in some locations. This is compounded by supplementary guidance which prevents grey belt sites from being subject to a viability test, which might otherwise allow a scheme to progress with less than the required level of affordable housing.

With no means of arguing that a particular level is unviable, developers would either have to find a way to make the scheme work or negotiate with the local authority to make a different kind of contribution.

Why has the government done this? Bell says: “It’s the point that sort of sits behind the premise, which is, ‘yes, we’re prepared to and recognise the need for green belt release to be more prevalent in order to meet needs, but we also need to recognise that we need to get more from those sites’.”

While it might have been odd to allow a viability test on what had been described as a “golden rule”, Bell believes a 15% rate above local policy could still risk undermining delivery on some sites, especially larger schemes.

Then there is the document’s removal of several references to “beauty” in terms of design. The word had been favoured by the previous Conservative government as a kind of carrot to persuade members of the public to accept development, as opposed to the stick of more structural planning reforms.

Seven instances of the word in the previous government’s NPPF, published in 2023, were removed in Labour’s July draft document, and these changes have been carried through to the final version. Although it still does call for “high quality, beautiful and sustainable buildings”, Labour’s decision to reduce the word’s prevalence reflects the party’s long-held suspicion towards what many consider to be a subjective concept.

Fears among the champions of “beauty” were compounded in November when Rayner shut down the Office for Place, an arm’s-length body tasked with ensuring quality design in new homes and driving the adoption of council design codes. While Bell says its closure, which will see its functions moved into the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, is “on the face of it, disappointing”, he does not accept that increasing housing targets equates to lower quality design.

“I think that the introduction of beauty was superficial. It didn’t add anything of meaning. It’s such a subjective judgment,” he says. “The previous government obviously just sprinkled beauty into various places in the NPPF. That doesn’t make any difference realistically to the planning process and how good design is achieved.”

Regardless of what is in the NPPF, Bell has faith that there is “a lot of passion” in the planning sector for quality design and is confident this can be achieved if the right resources are in place. By this he means funding for local authority planning departments, which have long been chronically under-resourced, a major factor in the delays at councils which have held back schemes in recent years.

While Labour has promised £46m to hire an extra 300 planning officers, this has been criticised by many, including Bell, as a drop in the ocean compared to what is needed. This is partly because of the higher salaries paid by private sector planning firms – “an age-old problem”, says Bell – but one which has been worsened by public sector funding cuts over the past 15 years.

“There’s a big issue of people leaving the public sector,” he says. “It’s not just about attracting those potential planners into the profession and into the public sector. It’s also about how we retain people within those officer roles so that the capacity is there.

“It’s not just a concern for local authorities. It’s a concern for the developer market because, if they’ve got aspirations to fulfill their ambitions but also the government’s ambitions, then we need strong resources within our local authorities to be able to support that.”

Capacity has also suffered because of the increasing complexity of planning applications, which now have to balance as more building regulations have been introduced on safety and the environment. Expectations for applications now, compared to when Bell started his career at Avison Young in Manchester in the late 1990s, are “hugely different… and it’s only going in one direction”.

“There is just so much more to read, to understand, to critique. And I think if there were means of changing that back, turning the dial back the other way, you know, reducing the complexity of planning applications, then that’s got to be welcome.”

A simplification of the planning process would certainly help Labour’s ambitions for decarbonising the UK grid, a controversial programme which Keir Starmer has warned will mean building new overground pylons across the country. This is set to be one of the government’s biggest battle grounds in the coming years, with campaigners and opposition parties already calling for more sensitive alternatives.

Turley sees huge potential for growth within the net zero infrastructure market and has recently appointed a new head of its net zero team. The firm is working on the expansion of the Scout Moor wind farm in Lancashire, and is gearing up for jobs in solar, hydrogen and battery storage.

While Bell hears concerns around the impact of these schemes on people who live near them, he says if climate change is to be addressed “there needs to be an acceptance that this infrastructure is going to be delivered”.

“You can listen. Absolutely, you can listen to public opinion and those that are on the ground being affected by things. We should listen. Whether that should mean that we stop the development or we prevent the development from happening – well, the planning system has never been applied in that way. It’s about judgment.”

The UK’s planning system has been a significant factor in why this country has a housing shortage, why HS2 ended up costing so much more than originally envisaged, and why no major onshore wind scheme has been built since 2015. But, while Bell admits reforming it is just one step in addressing the UK’s long term structural challenges, on a personal level he believes in what the government is trying to do.

“Frankly, what’s the alternative? If we’re going to address climate change, we need to move as quickly as we possibly can. And – a bit like housing need – if you don’t aim high, you’ll never achieve anything.”

No comments yet