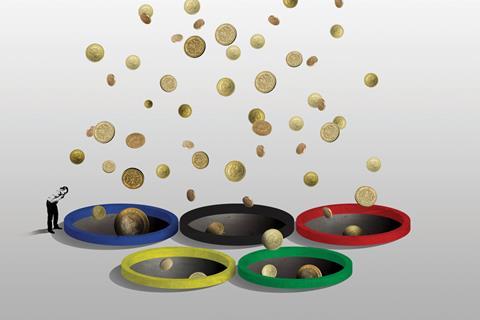

Everyone’s agreed that the Olympic park was hugely successful. But with questions raised over the cost of procuring the Games, is this a model other public sector projects should follow?

As Sir Steve Redgrave bore the Olympic torch into the London 2012 stadium towards the roaring finale of the opening ceremony, he passed a long line of hard-hatted construction workers.

The 500 men and women were there to represent those who designed and built the Olympic park: the contractors, subcontractors and consultants, along with the client, the Olympic Delivery Authority, and its private-sector delivery partner CLM, the consortium of Mace, Laing O’Rourke and CH2M Hill appointed in 2006.

It was recognition of construction’s outstanding achievement in delivering a highly complex £9.3bn megaproject on time, under-budget and to the high standard now plain for everyone to see.

The success is such that ODA chairman Sir John Armitt has recommended that the principles of procurement and programme management used by the ODA/CLM delivery vehicle are rolled out to apply to all public sector projects worth more than £10m.

However, while the ODA/CLM arrangement has clearly worked in delivering the venues, and hugely benefited the businesses involved, questions remain. As Building revealed last month, CLM is now expected to earn a final figure of £650m, 60% above the £400m

quoted by ministers when the final £9.3bn budget for the Games was agreed in 2007.

The ODA says the rise is down to VAT being excluded from the original £400m figure and extra work taken on by CLM. It concludes that CLM represented good value, not least because it was “integral” in generating savings of more than £1bn overall.

Notwithstanding this, the Public Accounts Committee has said it is concerned about the rise and has pledged to look into the numbers once the Games are over. Even if it agrees with the ODA’s assessment, could not a cheaper system be devised that would deliver such good results on megaprojects? Is Armitt right that the CLM approach is the only way forward? And can the 2012 Olympics, with its immovable deadline, cross-party political support and unique level of prestige, really be compared with other projects of a similar size?

Professor Leslie Willcocks, an expert in outsourcing at the London School of Economics’ department of management, is one of those warning of the dangers of trying to copy the Olympic procurement system. “It’s a bit of an exceptional contract … everyone wants to be associated with it,” he says. “You can try to copy what’s been done on the Olympics, but there’s a danger of trying to do this with people who don’t have the expertise.”

On the other hand, projects of a similar scale to the Olympics do appear to be able to attract a similar level of talent. Crossrail, for example - which is using a similar procurement structure, albeit with two private sector delivery partners fulfilling separate roles - is now employing many figures who worked on London 2012.

Crossrail head of procurement Martin Rowark is one of them, having moved from deputy head of procurement at the Olympics to his current role. He is full of praise for the ODA/CLM model and believes Crossrail’s “far more integrated” system has moved it on a step. Rowark says the Olympic client’s “rigid process and procedures”, its desire to understand and engage with the market from the outset, its use of programme management and its “sticks and carrots” approach were all crucial factors in its success.

He acknowledges that special purpose vehicles such as the ODA and Crossrail face a choice between trying to recruit the expertise found in a CLM-type consortium directly, and employing such a body as a joint venture, but thinks the latter is more sensible. He says: “Employing an organisation that brings with it a suite of intellectual capabilities makes perfect sense - it’s a solution to a problem.”

The questions around the CLM model are particularly pertinent when you consider the string of huge public projects planned by the UK following the Olympics, such as the £14.5bn Crossrail project, the High Speed 2 rail scheme and the Thames Tideway Tunnel.

Furthermore, the government is making efforts to reduce its reliance on private sector consultants across the board, for instance by training civil servants to help make government a more intelligent client (see box, bottom right).

You can try to copy what’s been done on the Olympics, but there’s a danger of trying to do this with people who don’t have the expertise

Leslie Willcocks, LSE

Announcing the initiative in February, minister for the Cabinet Office Francis Maude said it would “relinquish taxpayers from having to foot the bill for external consultancy to deliver the projects and services the country needs”. The government’s major projects supremo David Pitchford also warned that the public sector needed to up its project and programme leadership skills earlier this year. This is despite the fact that at the heart of the CLM model is the idea of outsourcing management of the programme to a private body.

John Mead, programme management director at Davis Langdon who has worked at CLM and for Crossrail, argues the flexibility of the joint delivery partner model makes it cost-effective because it avoids the recruitment and severance costs of employing staff directly. “When the government is funding a project on the scale of Crossrail or the Olympics, mobilising the workforce is difficult,” he explains. “If the ODA needed more people, CLM could provide them. If the ODA needed fewer people, the CLM companies could pull people back [to the three individual firms].

“I think we have found a really effective model for one-off projects of this scale.”But does the private sector really support the upskilling of the civil service? Some believe consultants and contractors pay lip service to this concept, but privately oppose it given that it would mean less work. But Alan Macklin, a director at CH2M Hill UK and a former programme and project management skills champion at the MoD, insists this is not the case, arguing that there will always be a need for private-sector expertise in this area, and that having a more sophisticated client in government would be a boon. “I don’t believe the private sector has a vested interest in preventing government upskilling: the private sector wants a more intelligent client to interact with - the ODA’s Learning Legacy website is a great example of this,” he says.

Ultimately, though, it is difficult to escape the conclusion that Maude is tinkering and that the ODA/CLM model is a tried-and-tested route governments will turn to in the future. After all, creating the level of public sector expertise needed to match CLM would require a level of spending almost impossible to envisage in the current economic climate.

As Willcocks says: “You are going to have to really invest to create that. Otherwise you end up with a litany of projects that are way over cost, underperforming and end up in front of the Public Accounts Committee.”

In contrast, the London 2012 procurement system has succeeded to such as extent that it was celebrated in front of the world as part of the opening ceremony. It will take a brave politician to venture too far from that.

Peter Smith: Not cheap, but was it good value?

The Olympic construction programme has been held up as a great success. The Olympic Delivery Authority, in particular, which engaged the CLM consortium as its delivery partner, has won plaudits for its procurement work, including winning the top prize last year at the Chartered Institute of Purchasing and Supply annual awards.

As a lifetime procurement professional and a commentator on major procurement issues, I was curious about how much the ODA paid CLM and what it got for its money. So earlier this year I posed a few questions under freedom of information legislation.

The responses make clear that CLM had an average of 472 staff working on the Olympic programme between 2008 and 2010. Combining that with the payments made to CLM, given in the ODA annual report, we worked out that the ODA paid an average of about £289,000 per head per year for CLM people over those three years.

The ODA said: “The rates are professional service rates paid to CLM and include employment costs, business costs and overheads. The rates include all CLM consortium members’ business and employment costs such as employer’s National Insurance contributions, pension contributions, medical insurance, vehicle costs, training costs, company business operating costs and head office costs.”

It looks like the ODA paid on an hourly rate per person basis, because when we asked about the 10 most expensive CLM people, we were told that the rate for the most expensive CLM person was £314.92 an hour, going down to £176.37 for number ten. (They wouldn’t give us job titles for those people, however).

Did CLM make too much profit out of the deal? Within the 472 people, there were, we believe, both staff seconded from the parent organisations (Laing O’Rourke, Mace, CH2M Hill) and independent contractors. My guess is the going rate for a good contract manager as an interim would have to be £600-800 a day. The average salary for the employed staff may have been about £60K plus benefits.

An average rate of £289,000 a year converts to an equivalent day rate of about £1,300 a day - so that would give CLM a pretty decent profit margin, whether we are talking about using independent contractors or staff from consortium members.

However, that £1,300 a day also includes the success fee element of the contracted payment to CLM, which from the figures Building has obtained is up to 30% of the total. And given that a blue-chip consulting firm will charge clients £1,300 a day for a pretty junior consultant in many cases, that sort of rate starts to look more reasonable.

My verdict? CLM did an excellent job. I met a few of its people and they were impressive - top level commercial, procurement, project and contract managers, often with a background in firms such as Bechtel, KBR and similar. There’s a strong argument that the individuals and firms deserve to be well rewarded for what they have achieved.

So was it worth paying CLM £650m of taxpayers’ money? Probably, given the importance of the programme, although it would be interesting to know just how hard ODA negotiated when the contract was awarded. But we must realise that good performance didn’t and doesn’t come cheap, particularly if this is going to be a model for other public sector construction and capital programmes, including perhaps even MoD acquisition.

And it also seems a shame that there does not appear to have been any skills transfer to civil servants. Could we not have had a cadre of 50 bright young civil servants learning from CLM, so the next mega-project might rely a little less on the outsourced option? Too late now, unfortunately.

Peter Smith is editor of Spend Matters UK/Europe, a leading procurement and supply chain website. Read his blog at www.spendmatters.co.uk

The ODA/CLM model and its possible alternatives

The delivery partner approach

The ODA, a non-departmental public body within the Department for Culture Media and Sport, opted to employ a delivery partner as a means

of mobilising the best private-sector expertise in construction quickly and efficiently.

Under the contract, the delivery partner consortium was incentivised to hit time and budget targets under the NEC3 contract and accepted a significant degree of associated commercial and reputational risk. CLM was also expected to adjust its resources over time according to the ODA’s requirements.

CLM’s role included programme and design management, value engineering, technical services, procurement project integration, quality assurance, cost control, safety, logistics and sustainability.

The GOCO

Another option is to set up a Government Owned Contractor Operated (GOCO) entity. This is the model that will be adopted by the Ministry of Defence for its forthcoming Defence Equipment & Support (DE&S) military procurement organisation. It is also the form taken by the National Nuclear Laboratory, which offers a range of nuclear services including decommissioning and is managed by a consortium made up of Serco, Battelle and the University of Manchester.

Applied to the 2012 Olympics, one could speculate that this model would have seen the government set up a CLM-type company and then advertise for a contractor or consortium

to run it.

Government client

Minister for the Cabinet Office, Francis Maude, is attempting to make the government into a truly intelligent client as part of wider reform of the civil service.In February this led to the establishment of the Major Projects Leadership Academy (MPLA) hosted by Oxford University’s Saïd Business School to train civil servants responsible for major government projects.

Even given such initiatives, bringing a government client up to the level necessary to deliver a project on the scale of the Olympics would also involve a major programme of private sector recruitment.

3 Readers' comments