From drones that do site inspections, to exoskeletons that save construction workers from back injury, to algorithms that crunch building codes to churn out thousands of design variants, artificial intelligence is ushering in a fourth revolution in construction.

When IBM’s supercomputer Deep Blue finally beat world chess champion Garry Kasparov in a 1997 rematch after losing the year before, few would have predicted that this gaming event – albeit a historic one – would have any significant bearing on construction.

But two decades on, and thanks to massive advances in the same artificial intelligence technology that enabled Deep Blue to win, that is exactly what is happening.

“The Kasparov game was absolutely critical,” explains Graphisoft vice president Ákos Pfemeter. “It was the first time a computer had beaten the human brain and it set the ball rolling for the rapid evolution in AI technology that has taken place ever since.”

While many may not even realise it, that evolution in artificial intelligence (AI) has now permeated all aspects of modern life. From the intuitive algorithms that power Google search engines and mobile phone keyboards to the intelligent digital assistants such as Siri and Alexa now capable of holding conversations with humans, AI technology has now bloomed to a global multibillion-pound technological and cultural phenomenon capable of performing tasks that Pfemeter describes as “a million times more complex than chess”.

And the next sector that AI is potentially set to revolutionise is construction. While industries such as car manufacturing and product design have long recognised and capitalised on AI’s potential, the two that have remained relatively resistant have been construction and agriculture. With the former at least, that is all set to change.

We need people with the skills and training to know how to fully optimise AI […] Plus some sort of mechanism needs to be developed that settles concerns over liability

Simon Rawlinson, Arcadis

And for industry expert Mark Farmer, author of the Modernise or Die report and chief executive of consultant Cast, AI can’t come soon enough. “Issues surrounding unsustainable margins and poor build quality have plagued construction for many years but now seem to be reaching a crescendo. Contextual use of AI can play a fundamental role in ameliorating these problems. The whole industry must embrace the fourth technological revolution together. In a way that makes sense for all parts of the sector. Failing to do this may lead to labour force cannibalisation, further market fragmentation and polarisation, at a time when industry needs to act more in unison – from SMEs through to major businesses. The development of new skills lie at the heart of this.”

Here, we look at the ways AI could revolutionise construction in the not-so-distant future, as well as those in which it is already happening.

Computational design

One of the biggest areas in which AI technology already manifests itself in the construction industry is computational design. This is essentially a rules-based digital programming where complex designs and advanced structures can be processed extremely quickly.

It is not exactly brand-new technology either.

As far back as the late 1990s, when he was working on his landmark Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, Frank Gehry was using computational design not just to help model the dynamic structure of the building but to determine the optimum shape and area of the auditorium that would maximise the number of generous viewing sightlines available.

Today, the most obvious examples of AI in computational design can be found in BIM modelling applications, a number of which are described here by Dan Kara, practice director in robotics, automation and intelligent systems at market intelligence company ABI Research.

“AI is already used in terms of seismic modelling of buildings in earthquake zones, ensuring quality control of building materials such as steel and concrete, and in developing safety and logistics strategies that determine the best location of materials on construction sites in order to minimise obstacles and accidents and increase safety.”

So if these functions are already taking place, what other construction applications might AI offer in the future? According to Daniel Hulme, chief executive of AI solutions provider Satalia, over the next few years we will see “AI tools that will be able to perform ever more complex decision-making”. For many industry commentators, this boils down to significant AI advances in three main areas, namely machine learning, robotics and design.

Machine learning

Machine learning encompasses the very essence of AI, because it involves machines learning specific skills or functions without being explicitly programmed to perform them. Kara speculates that this might mean “machines being able to respond to construction site situations in real time without the need for them to be continually connected and reconnected to back-end servers and for a human to then download and analyse their information”.

Within a construction scenario, Kara gives the example of drone technology as being particularly well-suited to benefit from machine learning advances. He cites the development of quadcopters – small, robotic, four-motor propelled objects – as indicative of this expanding technology.

“In the past two years, use of drones has already expanded significantly in the agricultural sector. In construction they are increasingly used for applications where vertical movement is required, such as site inspections, progress videos and information gathering. Machine learning could enable these processes to be carried with even greater speed and efficiency.”

Robotics

The technology that single-handedly captures the minds of many as the pre-eminent example of AI advancement – and one that could potentially play a huge role in the construction site of the future – is robotics.

“Robots are increasingly capable of performing a huge range of construction site duties,” explains Kara. “Machine digging, surveying, bricklaying, welding, demolition, excavation – these are all automated processes that a robot could potentially carry out more quickly and cheaply than a human.”

But even Kara acknowledges that robotics may have limitations on a construction site. He says: “Construction sites are not structured environments like a production line on a factory floor; they can be messy, uneven and exposed to inclement weather, all the things that robots don’t like.

“While robots can undoubtedly be more accurate than humans, their use on a building site might be optimised by concentrating on functions that require high repetition and heavy lifting, such as excavation and demolition. Away from site, robots – via 3D-modelling and printing – can also fabricate large-scale objects that humans can’t, such as columns and structural bracing.”

Pfemeter agrees. “Many people have an idea that AI will mean robots laying bricks on sites. But ultimately this is a dead end and would be a waste of AI’s potential. Bricks are their size and shape simply to conform to the speed and strength of the human laying them. Robotics would be far better suited to tasks which humans are too slow and weak for, such as excavation, on-site assembly and off-site modular fabrication.”

According to both Pfemeter and Kara, AI should not be used to answer human physical problems but to ask what machines are capable of: an important theoretical distinction. “We need to find the right problems for AI to solve,” insists Pfemeter. For him, one of the biggest of these is the final discipline that AI could be on course to disrupt: design.

Anything that requires complex decision-making is ripe to be disrupted by AI, and that includes the areas of programme management and co-ordination that are intrinsic BIM concerns

Daniel Hulme, Satalia

BIM

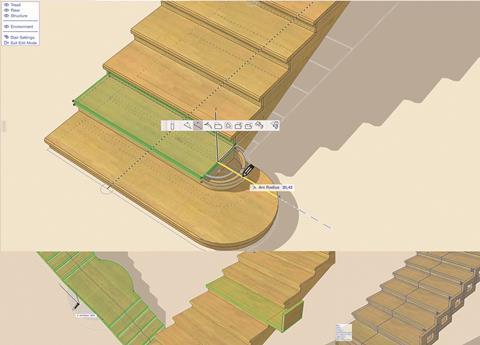

The role of AI here is not design in the aesthetic sense, but in the sense of parameters, as Pfemeter explains. “Architects rely on building codes to design, but everyone knows that regulations are full of contradictions. The challenge is to utilise AI to devise an algorithm that can learn building codes in order to intuitively develop thousands of design options that all comply with regulations.”

While Pfemeter maintains that recent Graphisoft BIM software attempts to do just this (on the design of stairs in particular), he has philosophical misgivings about whether one of the biggest obstacles to AI advancement might actually be – ironically – BIM itself.

He says: “BIM is predominantly concerned with output, not design. But AI is potentially very good at design in terms of analysing a huge database of options and then making intelligent decisions within a constrained environment.

In essence, BIM is too limited in its current form and will need to adapt in order to make full use of the opportunities AI offers.”

But not everybody agrees, as Hulme demonstrates. “Anything that requires complex decision-making is ripe to be disrupted by AI, and that includes the areas of programme management and co-ordination that are intrinsic BIM concerns.”

The issue of BIM and AI compatibility will be crucial in determining the impact AI has on the wider construction industry. While Arcadis head of strategic research and insight Simon Rawlinson in no way sees BIM in its current form as an obstacle to AI, he does believe it might not immediately produce the fertile ground AI will need to flourish.

“BIM has undoubtedly produced lots of data, but the culture of the building industry is still very paper based. Moreover, there is also a question of the kind of data construction produces. Can it be configurable for AI in the way that data in sectors like asset management can easily measure performance? Plus, there is the issue of ‘black’ data – the huge amounts of data still held non-digitally, or digital data that has no metadata and is therefore hard to make sense of or use.”

Impact

Despite these structural industry constraints, Rawlinson believes that AI has the potential to offer the industry huge benefits, citing “logistics, safety, automation, efficiency, lower costs, shorter programmes and better co-ordination” as some of the key advantages. But, he warns, two things need to happen first.

“We need people with the skills and training to know how to fully optimise AI – this really isn’t here at the moment. Plus some sort of mechanism needs to be developed that settles concerns over liability. If something can’t be proven physically and you’re relying on an intelligent digital projection, there needs to be a set of rules in place that builds trust and confidence that what is promised is going to be delivered.”

And Cast’s Farmer sees AI adoption as central to the survival of the entire industry: “A mass AI roll-out and even open sourcing of disruptive technologies would bring contractors, subcontractors and different-sized construction companies on to a level digital playing field, while fundamentally changing the way we design, build and manage the built environment. An AI-led productivity revolution should also be preceded by a gradual automation of different levels in the construction supply chain, so that all sub-sectors benefit. The risk is that the industry ignores its onset, which then leads to more disruptive structural changes in employment, skills and job roles that people are not ready for and which are out of their control.”

As Farmer intimates, AI has not always been viewed as the brave new dawn that will be a positive boon for mankind. Both renowned physicist Stephen Hawking and inventor magnate Elon Musk have been scathing about AI’s potentially reductive impact on human existence and the danger of replacing human jobs with those performed by machines.

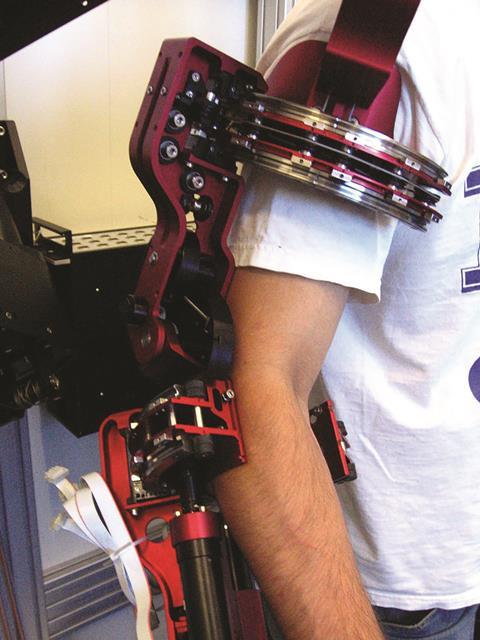

However, ABI Research’s Kara cites the development of the powered exoskeleton as an antidote to these fears. This is essentially a wearable full-body mobile machine that assists the wearer in performing repetitive or heavy-lifting tasks, increasing limb strength and endurance.

It can essentially be described as a robotic swimsuit. It is already used in a handful of airports and, says Kara, could form a significant aid to physical labour on construction sites, perhaps even adding a moral imperative to the AI revolution.

“Back injury is one of the biggest sources of sickness on construction sites, and exoskeletons can reduce injuries and actually help stem job losses by assisting manual labour and increasing worker safety. They thereby represent a way by which AI can add social and moral value. There is no doubt that AI technologies are going to happen. This could be one way of ensuring that the changes they introduce are a force for good for society as a whole.”

Follow Ike on Twitter @ikeijehView full Profile

No comments yet