The Chartered Institution of Civil Engineering president tells Mary Richardson why she thinks the industry must get smarter when it comes to educating its future professionals

When Building meets Alison Watson, it becomes clear that her passion for the transformative power of great vocational training has its roots in the story of her own personal and professional life. She tells us why she won’t rest until the sector starts to take more seriously its responsibilities for educating the next generation of built environment professionals.

“Simply to ‘inspire’ is not enough,” she says.

To her, meaningful engagement with young people requires hands-on, creative opportunities which show them the potential of a career in the built environment.

One example is her latest project – a fun and practical initiative where young people get to design a new restaurant for Jamie Oliver, blending real-world experience with aspirational learning. More about this later.

Early loss

Watson had some missteps and false starts on the road to the career in surveying that has meant so much to her. Her working-class Yorkshire childhood was marred by the death of her dad when she was just 13.

He was a stonemason, while her stepfather was a joiner who became technical director at Sheffield Works Department. So, she grew up in a household supported by the construction industry.

But “no one talked about their work at home,” she says. And, in any case, careers in construction were not recommended to girls in the eighties.

Instead, careers teachers steered her towards nursing, because she had a “caring” disposition, or maths teaching, because she had a head for figures. But she liked her maths applied rather than pure, and in those days, that meant opting for FE college rather than sixth form. And the less-than-inspiring teaching she received there would later ignite in her a desire to do better for today’s young people.

Discovering surveying

Disenchanted with education, and not sure what to do with her life, she turned away from dreams of university and instead got a job in a bank. This made use of her mathematical abilities – but bored her rigid.

This is where the tale takes an unexpectedly romantic twist, because it was falling for a man that got Watson into surveying. He was a civil engineer who took her out on-site to be his “chain lad” and help with setting out (marking out buildings on the ground).

She fell for the job as much as the man and, before she knew it, she was training to be a surveyor.

The relationship didn’t last. But her passion for her new profession did. And, in time, Watson found herself in a new relationship, set up her own surveying company, had a daughter, and soon afterwards won a contract to survey schools as part of the Blair government’s Building Schools for the Future programme.

Working in schools

In one school, the head warned her not to survey during lunch break but, “I didn’t have time to take his advice,” she says. “When the bell for break rang, the kids swarmed out and headed straight for my £30,000 piece of surveying kit.

“I have never run as fast in my life as I did to get over to protect that equipment! But incidents like that made me realise the kids were really interested in what we were doing.” And that realisation sowed a seed…

“I played games with them. We would imagine a topographical survey as a treasure map, or use their knowledge of height to guess ‘how far?’. I would get children to lie end to end to check their guesses. They laughed as they learnt, and soon it evolved into little workshops we would run at break times.

“I found it frustrating, though, because, even though the children might have a great time with us, they had nowhere to take that interest once we had left.”

Forming a company

It was this experience that prompted Watson to set up her own business, Class of Your Own (or COYO), which would allow her to take those learning opportunities to more schools. She began in 2009 by putting a built-environment spin on the enterprise workshops often run in schools.

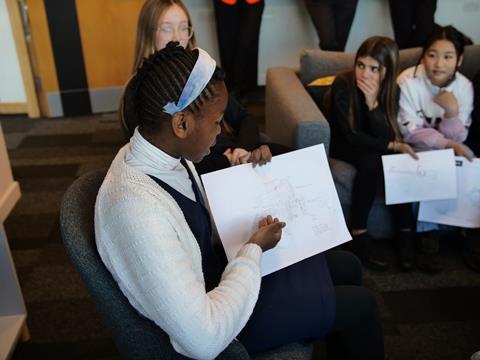

She explains: “Instead of typical enterprise activities – designing and selling mugs, say – we got them to design an eco-classroom to teach their local community. In teams, with different children taking on roles like land surveyor, landscape architect, sustainability officer, and so on. The children were also empowered to help their families do better in their own homes.”

These proved a great success. “The kids knew nothing in the morning, but by the end of the day, they were talking about ‘building services engineering’ and recommending renewables.

“Designing a building teaches you about so many different things. The built environment has all the other subjects within it: history, geography, maths, science – you name it, it’s there.

“A teacher called me after we had been in to do a workshop, saying, ‘The kids are all pestering me about how do they become a land surveyor, or this or that job’. And I realised then that we needed to develop a whole curriculum.”

A disconnect between young people and the world of work

The construction industry has long struggled to attract young people, facing a persistent image problem and a lack of awareness about the opportunities it offers. This challenge is compounded by the UK education system, which has historically failed to prioritise vocational training. Despite some recent efforts, the system still struggles to effectively engage students in practical, career-focused learning.

>> See also: Labour’s plans for growth hinge on attracting new skills to construction

The knock-on effects of this are significant, contributing to skills shortages in key areas and leaving employers grappling with a lack of work-ready candidates. At the same time, the UK faces a crisis in underemployment among young people.

Many are disengaged from the world of work and unaware of the wide range of opportunities available to them – particularly in the built environment, a sector with enormous potential to provide rewarding careers while addressing pressing social and environmental challenges.

Developing a curriculum

Working with Peter Horsfall, a professor of professional work-based learning at Liverpool John Moores University, Watson developed a new approach to teaching in schools. She explains: “Not only would the teachers be teaching a really necessary subject, but they could become de facto careers teachers too. I wanted to create a subject where children learnt through the lens of professional development.”

This vision led to the creation of the Design Engineer Construct! learning programme, now affectionately known as DEC. Watson smiles as she adds: “In many schools, DEC is a favourite subject. It’s also still fun.

“It was important to me that the young people would use industry-standard digital design tools. I didn’t just want them to be making interesting buildings. They had to be able to analyse them too and justify their ideas.

“ ‘Let’s look at the sustainability of your building over the next 25-50 years, taking a cradle-to-cradle approach.’

“These were not privileged children. We started at Accrington Academy, and I remember I got a letter from a parent moaning how her son had begun nagging her to switch things off, put less water in the kettle, and so on. But the letter ended: ‘But the money we’ve saved by listening to him has enabled us to buy him a new pair of shoes.’ That still moves me to this day.”

Qualifications

Since 2013, DEC has included regulated Level 1, 2 and 3 qualifications – think Foundation, Intermediate and Advanced level – offered through technical qualification awarding organisation TQUK. At each level, students design their own building using the latest, industry-standard software.

The subject is usually taught by design technology subject teachers, who generally begin with little knowledge of the industry but receive comprehensive training.

Awards and work experience

COYO also offers smaller design projects, known as DEC awards, suited to after-school clubs or home-schooling as well as the school timetable. The latest of these invites pupils to design a sustainable restaurant for Jamie Oliver. Virtual work experience is available too, as are structured programmes to support work experience in industry.

Adopt a school

DEC courses are already offered in dozens of schools and are expanding around the world, and COYO has already partnered with many big names in the sector. But Watson’s vision is to see the DEC programme offered in hundreds more schools.

To achieve this, she needs more firms to come forward and “adopt a school”. She is keen to point out that “it counts towards social-value obligations”.

For a relatively small investment – and a commitment to work in partnership with the school – firms can adopt a school for three years or more to deliver the DEC programme. Watson says: “Working with schools has never been more critical, but if we want to have a genuine impact on society, we’ll stop talking about a skills gap and start talking about the significance of real, applied knowledge.

“Education should be the golden thread for every organisation. I look forward to the day when a mock interview is not something we do to tick a box – we just interview for real jobs, knowing that DEC students are work ready.”

Careers in industry

As for the children participating in DEC programmes, many have gone on to take up careers in the sector. Most start DEC well before they are 16, and it’s this formative approach – blending real-world experience with academic learning – that they cite as all-important.

The young people often highlight how the programme not only opened their eyes to the opportunities within the built environment but also provided the support and inspiration of excellent teachers who guided them along the way.

>> Also read: From the ground up: Ackroyd Lowrie on a mission to turn school leavers into architects with real work experience

Watson was awarded an MBE in 2018 for services to education. She was recently elected president of CICES, where she has chosen “Make Space for Education” as the theme of her presidency. She has recorded a video discussing her passion for education, sharing her vision for inspiring more young people to explore rewarding careers in the industry.

What’s next?

Her work is a testament to the power of education to transform lives. Through DEC, she has created a pathway for young people to not only imagine themselves in careers within the built environment but to gain the skills, confidence, and knowledge to succeed.

Her approach combines practical learning with real-world application, ensuring that students leave the programme ready to contribute meaningfully to the industry and society at large.

Looking ahead, Watson shows no signs of slowing down. With a DEC primary curriculum in development and plans for infrastructure and digital-twin projects, she is continually expanding opportunities for young people to engage with the built environment.

Her efforts are not just about filling the so-called “skills gap” but about redefining how we think about education – making it a tool for empowerment and a bridge to rewarding careers.

For Watson, the mission remains clear: education should inspire, prepare and connect young people with the world of work in a way that is meaningful and lasting. As she says, “Simply to ‘inspire’ is not enough.” Through her leadership, DEC is setting a powerful example of what’s possible when education and industry collaborate to create a brighter future.

No comments yet