It is clear to all that the future of power generation in the UK cannot be coal-fired. So why has the government so far failed to set a clear strategy on renewable and nuclear energy? Roxane McMeeken presents the final part of our Charter 284 manifesto

At 10.15pm on Tuesday 10 November 2009, without warning, 60 million people in Brazil were suddenly in darkness. In 800 cities, including São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, every light went out that wasn’t connected to a battery or back-up generator. Metros came to a halt. The bus system collapsed. Police rushed onto the streets to deter looting, and there were widespread reports of road accidents.

In short, 40% of people in the fifth most populous country in the world spent five hours in a very scary place they used to call home. Over in Paraguay it was worse: the whole of the country went black.

Brazil’s Operator of the National Electric System said the blackout occurred because 17GW of power – the amount used by São Paulo – suddenly dropped out of the national grid. Brazil’s government blamed the outage on three major power lines from the giant Itaipu hydroelectric dam on the border with Paraguay. But experts say Brazil should have had sufficient back-up systems to cope with the lightning, rain and high winds that caused a short circuit in the power lines that night. Jon Dedman, head of energy at Davis Langdon, says Brazil’s blackout demonstrates in the starkest terms the consequences of failing to maintain the national power infrastructure adequately.

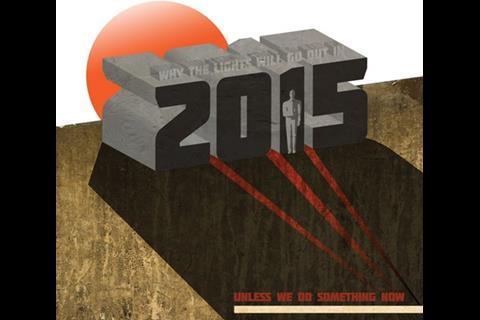

What has this got to do with the UK? Well, when we read headlines about the lights going out if we don’t find new ways of generating power, this is the sort of scenario they are referring to. Britain is facing an energy crisis if we don’t fix our crumbling power infrastructure. Moreover, we are looking at the lights going out in only four years. Dedman says: “This threat is not just a scare story. We have a situation at the moment where the nation has not addressed a crisis that is looming in 2015.”

Our current generation of power stations, which were mostly built in the seventies, are due to be switched off in the next few years. Some 15% of them will shut down by 2015. Although there are plans to replace them and extend the lives of some facilities, Dedman says the rate at which we are building new plants is not fast enough. The result: anyone who isn’t in a hospital or a bank “could end up sitting in the dark, or the freezing cold, for who knows how long”.

This is why prioritising the development of energy is one of the five demands of Building’s Charter 284 campaign. Here we explain why, following the election, the new government must develop nuclear and renewable energy specifically, and why this must be achieved through incentives for private sector investment.

The UK’s energy triad is made up of coal, gas and nuclear. Together they supply the vast majority of our national energy. Renewables make up 6%. This cannot continue for several reasons, besides the obvious economic imperative. The first is legal: the EU’s April 2009 Renewable Energy Directive requires the UK to provide 15% of its energy from renewable sources by 2020. According to Dedman, meeting this target will cost about £100bn. Exactly what happens if we don’t is not clear, but the UK government would face prosecution in the European Court of Justice. One senior industry source says: “I’d guess the EU’s penalties would be higher than the cost of developing the renewables sector.”

The second reason is ecological. The UK government’s policy of cutting carbon emissions by more than 750 million tonnes between now and 2030 cannot be met without moving away from hydrocarbons.

The third reason is geopolitical. Gas is a much cleaner fuel than coal, and Britain’s dash for gas in the nineties did greatly improve its carbon footprint. A gas-fired power station is cheaper and much faster to build than a coal-fired station, and gas is a cheaper and more convenient energy source. But David Simpson, energy partner at KPMG, says it is not the answer. The problem with gas is that Britain’s stock in the North Sea is running out. Currently, we get 60% from the North Sea and import the rest. In five years, we will be importing 80% from countries such as Russia and Qatar. Prudence dictates that we do not become over-reliant on these countries for our energy, especially when one of them has a record of using it to exert political pressure, as the Ukraine recently found out.

Moreover, Dedman says the UK has fewer than 10 days’ worth of stored gas. Germany, in contrast, has 30. So while the Germans would have a month to negotiate with Russia in the event that it turned off the pipeline, we would have just over a week.

Nuclear is not exactly a low-carbon power source: huge amounts of energy are needed to mine and refine uranium for the fuel rods, and to build and decommission the plants. However, it emits no significant carbon once the station is up and running – a period that some experts say could last for up to 60 years with a third-generation reactor.

But we should not aim to rely on nuclear alone. As Stephen Wells, group strategy and business development director of Costain, says, “it is common sense that we should not rely on a single source of power”. In any case, the first new station won’t be online before 2017 at the soonest. By contrast, a wind farm can be built in under a year, according to windenergyplanning.com, although getting one through the planning system can take another two and a half.

For these reasons we are advocating investment in a new energy triad: nuclear, wind and mixed renewables. But where is the money to come from? The government is in no position to provide the £100bn Davis Langdon says is needed to meet our 2020 EU renewables target, and the £150bn or more to build the 10 nuclear power stations and supporting infrastructure envisaged.

Unfortunately, the private sector is also reluctant to come up with the money, partly because we live in straitened times, and partly because the government has not succeeded in setting out the policy framework that the private sector needs to calculate its return on investment. Rather, Dedman says the government’s strategy is “fragmented”. For instance, feed-in tariffs have just been agreed for renewable projects up to 5MW, but projects above this capacity “have no agreed tariff and will therefore find it extremely difficult to obtain funding”.

Dedman’s solution is for the government to create a framework that encourages investment and integration. “This should provide a mechanism that allows any new form of energy to come to market on an equal basis. The mechanism should provide benefit to all forms of energy generation, certainly until such time as renewables can be considered a viable alternative.”

Here’s how the development of nuclear and renewable energy through private sector incentives should work …

Nuclear

Last year the government sold 10 site licences for nuclear power stations to companies including EDF, Eon, RWE and Iberdrola. These projects have the ability to secure our energy supply, cut carbon emissions and help to create a diverse energy mix and replace the existing generation of coal, gas and nuclear power stations. Costain’s Wells adds that developing the capacity to build these nuclear power stations will also create skills that we can export, further boosting the UK economy.

So far, so good. But the problem with getting these nuclear power stations up and running is that the nuclear business is still relatively unattractive to the utilities that will run them, for the reason given above: the cost of building a nuclear power station is up to £6bn and the process could take 10 years, and after that there is no guarantee of the price at which the operator will be able to sell the power generated.

Another element of that policy framework that is missing relates to fossil fuel generation. This is still a lucrative business, which means that a rational energy utility should be building more plants. Dedman says: “Clearly the government should be discouraging that it if it’s going to hit its emissions target.”

There is a debate around how to incentivise the development of nuclear power, but one way to achieve this and simultaneously discourage carbon-emitting approaches would be through government intervention in the carbon trading market. For nuclear power to become an attractive business for utility companies, carbon must be made expensive enough to mean that generating power through non-carbon-emitting methods becomes economically preferable. The government should therefore set a minimum cost per tonne of carbon. Dedman says: “The large fossil fuel power generators have to buy carbon credits to offset their carbon emissions and if the price is extremely low, as it is presently, the financial penalty is such that the price to generate is very cheap. If a sensible floor is set that increases the cost to generate to similar levels to that of nuclear, then this will make investment in nuclear new-build viable.”

Wind

Mark Whitby, co-founder of consulting engineer Whitbybird, and now an independent consultant, is a fervent supporter of wind power. He concedes that wind farms, especially if offshore, are expensive – Davis Langdon reckons that of the £100bn the UK must spend to reach the EU target of 15% of our energy coming from renewables by 2020, most will be spent on wind energy.

Whitby argues that the more wind farms we build, the greater the economy of scale and the lower the unit cost. On top of that, the industry has the potential to be a major employer as well as an export earner. “The wind generation has the potential to be a £5bn UK industry within five years. There are huge opportunities for young people to get into the wind industry now.”

Paul Stapleton, the head of energy at EC Harris, adds that the localised nature of wind energy means it will spread jobs around the country, too. “There will be all sorts of little industries springing up around the wind industry.”

As with nuclear, the private utilities must be incentivised to take the risk of investing in wind farms, which are still an expensive and relatively untried technology. One way to do this is with renewable obligation certificates (ROCs), which were introduced in 2002 and oblige electricity suppliers to source increasing amounts of energy from renewables. For example, in 2005/06 it was 5.5% for the UK and it has gradually gone up to 9.1%. Suppliers meet their obligations by presenting ROCs. For each megawatt hour of green electricity a company generates, it receives between 0.25 and two ROCs, depending on how well established and how clean the technology it is using is.

Where it does not have sufficient ROCs to meet its obligations, it must pay an equivalent amount into a fund, which is used to pay back those suppliers that have presented ROCs.

Stapleton says ROCs are the way to encourage wind power but they don’t go far enough. “We are not alone in our development of renewable power – the whole of Europe is doing it, so we need to attract international investors. We must make the UK the most attractive environment for investing in renewable energy.”

At present the seas surrounding the UK are where the wind blows longest and hardest, but to make it attractive financially, ROCs should go further. Stapleton says wind powered electricity is usually awarded between 1.75 and two ROCS for each megawatt hour, but should get three. He says: “This would require cross-party political support but it has to happen. Either we do what we normally do and dither around the edges or we go for it.”

The industry shows its support

Rob Smith, senior partner, Davis Langdon

Our power generation fleet is old and has a detrimental impact on the UK’s carbon footprint. Unless it is replaced with carbon-friendly alternatives there is little hope of meeting the commitment to the Renewable Energy Directive for 2020. The government must set a clear strategy on how to achieve these commitments and it must provide a financial framework that allows all forms of carbon friendly power to compete on an even basis.

Dorothy Thompson, chief executive, Drax

At Drax power station, our focus is on delivering meaningful carbon emission cuts in the here and now. For example, through co-firing biomass with coal we can make an important contribution to the transition towards a low-carbon economy.

By mid-2010, we will have the capability to produce 12.5% of our output from renewable biomass materials. However, government policy stands in our way. Biomass is much more expensive than coal and without a level playing field with other renewables our ability to make the most of this opportunity to cut CO2 is limited. Without fair support from the government, biomass’ ability to play its part in a balanced, secure energy mix is gravely undermined. This is a very serious issue because biomass is a key component for delivering the 2020 target.

Vince Clancy, chief executive, Turner & Townsend

We desperately need a longer-term national strategy that supports major energy production via nuclear, but also far greater deployment of decentralised renewable energy installations.

The only viable way to achieve this is for the government to invest alongside the private sector. The government needs to provide an intelligent incentive mechanism and stable platform which encourages private sector investment.

From a UK plc perspective, we must ensure that we not only grasp the importance of converting to a low-carbon economy but that we also do it in a way that creates competitive advantage.

Postscript

Sign up to our campaign! You can register your support for Charter 284 at www.building.co.uk/charter284

No comments yet