A £100m infrastructure modernisation programme is under way in Antarctica but it presents some unique challenges – like having to move elephant seals out of the way and being 1,000 miles from the nearest builders merchants. Elizabeth Hopkirk finds out about the hardships and rewards that come with working in this most remarkable environment

“People are quite surprised when I say this, but a Scottish winter is probably worse than working in Antarctica,” says Bam Nuttall’s Graham Hopper. The civil engineer, speaking via Zoom from his native Inverness, knows a thing or two about remote locations and hostile conditions – as does his employer. His previous projects have included tunnelling through mountains on rain-lashed Scottish islands to build hydroelectric schemes.

By contrast, the weather in an Antarctic summer – roughly November to April, the only time when construction is possible – can be positively pleasant, he says. It is relatively dry, often sunny and sometimes the temperature even edges above 0ºC. The scenery is also spectacular and the snowboarding passable. You just need to watch out for elephant seals on your way to the office.

The success of anything in the Antarctic has to come from pre-construction planning, building confidence and mutual respect so we can assess what is best value for the project, not a race to the bottom

Graham Hopper, project director, Bam Nuttall

You would have been forgiven for assuming that the biggest challenge facing a contractor and design team at the bottom of the world was the inhospitable climate. The ground, even when not covered by hundreds of metres of snow and ice, is underlain by permafrost harder than concrete, the temperature is routinely below the point at which cheap steel shatters and it is not unusual for the wind to be a bracing 70mph. But, says Hopper, building in difficult conditions is just “what we do”.

The more taxing side of the project is the logistics: from picking the right team to transporting them, the kit and materials almost 10,000 miles to the Antarctic Circle, a place where, if you realise you have forgotten the screws, you are at least a thousand miles from a builders merchants, not to mention the nearest hospital.

Packing the ship is an art – especially when the only place you can fit the 300-tonne crane needed for unloading is at the bottom. Before waving off a vessel, Hopper always asks who has the keys to the hold – and he is only half joking.

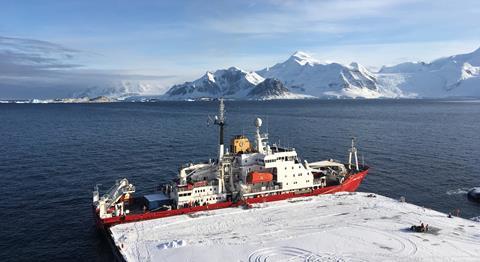

Bam Nuttall has been working in Antarctica since 2016 for the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) with design partner Sweco, client-side technical adviser Ramboll, cost consultant Turner & Townsend and, respectively, concept and delivery architects Norr and Hugh Broughton. Projects have included building a wharf big enough to handle Britain’s new polar research ship, the RRS Sir David Attenborough (forever Boaty McBoatface to some). It has been a satisfying experience for all involved, he says, and the relationship has just been renewed. Bam Nuttall and Sweco won the tender earlier this year for a 10-year framework to modernise BAS’s largest research station, Rothera, which is a collection of khaki 1970s and 1980s buildings on a rock promontory on the mountainous and heavily glaciated Adelaide Island, lying just off the Antarctic Peninsula, the continent’s westerly “tusk”.

Members of the wider team spoke to Building about what it is like to work in Antarctica and in particular about the design and construction of the huge Discovery Building, the most interesting element of the £100m Antarctic Infrastructure Modernisation Programme (AIMP). This 4,500m² building will consolidate the operational and some of the recreational facilities for a team that can number 140 at its summer peak but dwindle to 20 in the winter when temperatures plunge to -70ºC. It will replace more than half a dozen buildings that are reaching the end of their lives.

The programme has been somewhat delayed by the coronavirus pandemic. Although strenuous testing and quarantining has kept covid-19 out of Rothera so far, constraints on international travel disrupted the end of the 2019/20 season and cut the most recent season to just 10 weeks.

By the time they left in March, Bam’s 24-person team had managed to complete the groundworks for the Discovery Building: foundations, drainage and retaining wall. But the floor slab, steel frame and cladding will be tasks for next summer, which begins in November. Handover of the building, which is named after the first sighting of the Antarctic mainland in 1820 by British naval officer Edward Bransfield, is now scheduled for 2024.

The Discovery Building: designing out snow and isolation

The brief for Discovery packed a lot of functions into its large, 90m x 30m footprint. Initially two buildings were considered, but one envelope is more efficient for many reasons, including snow clearance. This hugely time-consuming and expensive task happens daily as well as at the start of every season, a process known as dewinterisation when the site and vehicles are dug out and many tonnes of snow moved.

People often associate buildings in the Antarctic with stilts which stop snow drifting against walls or, more problematically, doors. Hugh Broughton’s memorable Halley VI research station was built on skis so that it can be towed away from cracks in the ice shelf on which it stands. Rothera – three hours’ flight away – is an entirely different proposition as it is built on bedrock.

BAS wanted ground-level access because getting people and vehicles in and out is much quicker and safer without relying on icy ramps, but it also needed to find a way of managing snow accumulation. The design team flew to Ontario in Canada to work with specialist snow engineers RWDI. Norr associate Ross Bridgman, architectural lead for the project, describes how they plunged a physical model into “an enormous rectangular fish tank”.

At one end a series of propellers simulated the prevailing wind. Fine grains of sand in a perforated pipe slowly drifted towards the model. After half an hour they switched off the fans and drained the water, letting the sand settle. They adjusted the model and the process was repeated.

“It was so ingenious and so simple but really effective,” says Bridgman. This method informed the decision to orientate the long axis perpendicular to the prevailing northerlies to take advantage of the natural “scouring” in which snow is blown over the building and dumped on the leeward side. It also helped them to design a curved wind deflector, the biggest in Antarctica, which will run the length of the roof and has been internally strengthened to resist the wind. The hope is that this will force the snow to be dropped a few feet from the southern elevation, making it much easier for a snowplough to clear.

Internally, the two-storey building is zoned around a large central store which can receive pallets straight from ships, replacing several smaller stores where everything had to be unpacked by hand and the contents stashed wherever space could be found. Surrounding the store are workshops, plant, a garage for skidoos and snowploughs and what is known as the preparation area, where all the kit for field operations can be laid out. Scientists sometimes camp out for months while conducting the research, which is shaping our understanding of climate change, among other things. At the quieter eastern end are medical facilities, workspaces and recreational areas such as music and craft rooms, plus a gym and a climbing wall useful for crevasse training.

“The layout has been designed to foster wellbeing and collaboration by encouraging incidental meetings, which is good for knowledge sharing between the teams,” says Bridgman, who more often designs further education colleges but also Ministry of Defence projects such as the Lynx helicopter training facility at RAF Yeovilton. “We were also conscious that you could go for quite a large part of your day without seeing many people.”

To help avoid this, sections of the building can be closed off in winter. Vibrant use of colour, including a red staircase, is intended to counter seasonal affective disorder and natural light is maximised wherever possible, with rooflights augmenting the triple-glazed windows which have been kept small to reduce heat loss.

For the envelope, the team developed a bespoke composite panel system with BRE using off-the-shelf materials including an insulation core of very limited combustibility sandwiched by metal. Non-combustible mineral wool had to be rejected because it loses its thermal properties when wet. Copper, timber, aluminium and titanium were tested for the cladding. Ultimately steel was chosen (sky blue to resist fading).

“BAS felt their estates team had experience of steel cladding and composite panels and introducing a new material that might have been exciting was a bit of a risk, especially given the size of the building,” says Bridgman with only the faintest air of disappointment.

“It’s important they have a building they have a lot of confidence in.”

BAS’s decarbonisation vision is embedded in the brief. The station and its ships are currently powered by marine gas oil (MGO), and one aim of the modernisation programme is to cut emissions at Rothera by 25%. The new building is targeting BREEAM Excellent through thermal efficiency and stores, facade-mounted PVs, combined heat and power generation and mechanical ventilation and heat recovery.

Dave Brand, BAS’s project manager, predicts this will save 7,000m3 of MGO a year. He describes BAS as taking tentative steps towards net zero carbon. In the next phase they will bring in more renewables, but he says that this phase is about demonstrating as big a reduction in demand as possible before tackling supply.

One final design challenge: elephant seals like to cuddle up on a wooden bridge between the bedrooms and dining room and can be quite aggressive as well as damaging kit. In a bid to discourage this, there are plans to construct an alluring timber platform away from the base.

People: Avengers Assemble

It is the proximity to nature – fur seals, whales, penguins and an extraordinary landscape are among the other attractions – that makes the privations worthwhile. “A lot of hands went up in the studio when we were appointed,” says Bridgman. “It’s a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.”

Some of the hands go down again once people understand quite what a hardship a posting in Antarctica is, despite enhanced pay and efforts to make the station homely. Picking the right team is critical. People must be physically healthy as well as able to withstand loneliness plus prolonged darkness during the shoulder months. They can’t jump on a plane if there is a crisis at home, or at Christmas, and their families need to be prepared too.

The fewer construction workers you bring the more room there is for scientists, which means Hopper is looking for people with multiple skills. “You want key people at the top of their game,” he says. “It’s like Avengers Assemble.”

Everyone is handpicked, so Bam does not use many subbies. Attitude is crucial because the station operates as a single team, with contractors taking part in station life alongside the science and operations staff. They eat together, socialise together – and, if a ship comes in, everyone is expected to help unload.

BAS’s priorities have been shaped by 60 years of working in Antarctica and the collaborative approach starts with procurement. Hopper’s team was embedded in the client’s Cambridge offices and early engagement was key. “We really became one organisation,” he says.

“BAS deserve a lot of credit. They realised they were asking contractors to come to the most hostile, highest, driest, coldest, windiest continent on Earth and they identified that the foundations of success would be a partnership built on collaboration rather than the historic transactional approach construction may have had in the past.”

It also helps that BAS, understanding that contractors will be nervous, is prepared to take on some of the low-likelihood but potentially high-impact risks. “The success of anything in the Antarctic has to come from pre-construction planning, building confidence and mutual respect, so we can assess what is best value for the project, not a race to the bottom,” says Hopper.

“We would look at risk and not try to pass it on but think who might be best placed to manage and mitigate it. It’s about understanding the risk and cost drivers across the organisations.”

It seems to work. “We have delivered a number of projects safely, in budget, on programme, with no environmental damage and with people who want to go back,” he says.

Logistics and planning

The first principle of construction in the Antarctic is that everything is reversible, so the site could be restored to its pristine condition. Plans must be evaluated by the Foreign Office and the signatory nations to the Antarctic Treaty. Noise, dust and vibration are monitored throughout the construction process.

To minimise contamination and water use, all the concrete for the foundations, slab and walls is precast in the UK. Materials and equipment are delivered to a central hub up to six months before the voyage and packaging is disposed of here. BIM and 4D modelling allow the team to “build it before we build it” for greater assurance.

Sometimes they physically build elements in the UK too, which saves time on site, but the amount of prefabrication is limited by the need to squeeze everything into 500-odd shipping containers without voids that insects could get into. Biosecurity is a serious business. And each ship costs £1.5m to charter. The build programme is carefully mapped in advance with “no-go” stop points so, if a project is not complete at the end of a season, it is left in a safe and weatherproof condition.

It all adds up to an immense challenge. The motivation for everyone to whom Building spoke was the chance to be involved in something exceptional and, above all, meaningful. Hopper recounts the famous story of JFK visiting Nasa and asking a janitor sweeping the floor what he was doing. “Mr President,” he replied, “I’m helping put a man on the moon.”

Hopper adds: “BAS are scientists ultimately trying to save the planet. I want to make it easier for them to do their critical work. Who wouldn’t want to be part of that?”

To the end of the earth

It takes at least three days and three or four flights to get from Heathrow to Rothera, the UK’s Antarctic research hub, while the diggers and materials take 30 days to get there by ship. The final five-hour leg from Punta Arenas in Chile is by bright-red propeller plane, with a pilot’s-eye view if you are lucky.

“It’s really quite exciting,” says architect Ross Bridgman of Norr, who has been to Rothera for three short trips. “You see the mountains growing as you approach, then I saw my first iceberg and then a seal sitting on an iceberg.” And that’s just the appetiser.

“Each morning, as you make the short walk to breakfast – possibly stepping over seals or watching them play-fight – you are looking at a beach with icebergs and a backdrop of mountains. Every evening we would go for a walk around the point, past colonies of penguins and packs of humpback whales.

“It’s surreal. The place is quite different every day because the icebergs turn. One night I heard this roaring sound and was told it was an iceberg flipping.

“One Sunday they took us out in a big motorised dinghy to see an iconic iceberg like a double bridge and a glacier that ends at the sea with an enormous wall of snow and ice like in Game of Thrones. It was sunny and at first I wondered if we needed all the layers, but I took my glove off to take a photo and after a minute my fingers were stinging.” The wind chill is powerful but so is the sun. Every boot room has sunscreen points as well as handwashing stations.

One positive of the limited internet and no phone signal is that people are not staring at their devices and are more present to colleagues and the scenery, which Bridgman describes as refreshing. There is also the chance for some winter sports, with skidoos in place of ski lifts. Bridgman and Bam Nuttall’s Graham Hopper both got the chance to go snowboarding. “Not everyone can Strava a snowboarding trip in Antarctica,” grins Hopper.

No comments yet