Here is a reminder of some of the features that stood out for our readers

Every week Building publishes the big-impact stories that affect companies working in the wider UK construction industry.

>> See also: Best of 2024: interviews

>> See also: Best of 2024: news stories

Here we have compiled a list of the most-read features from the past year:

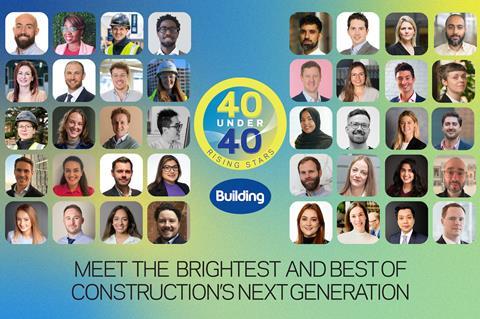

40 Under 40: Meet the brightest and best of construction’s next generation

Building shines the spotlight on 40 people under the age of 40 who seem set to change the future of construction

Meet 40 rising stars who will be shaping construction in the decades to come.

Over the past few months Building has received nominations for the ones-to-watch from all corners of the industry, reflecting its huge variety of disciplines and fields of expertise.

This class of 2024 shines the spotlight on impressive talent already working in the built environment – from site managers and planners to sustainability consultants and digital tech experts.

Their uplifting stories show just how exciting and rewarding a career in construction can be, offering rapid progression and high levels of responsibility early in people’s careers.

>> Click here to read the full story

The longest job: Finishing Gaudí’s masterpiece, La Sagrada Família

How do you recreate the work of a genius out of nothing but rubble? And even if you can, how do you keep a construction project that was started in the 19th century from going off the rails? Building went to Barcelona to find out

Little was left in the workshops but shattered plaster.

It was the summer of 1936 and Catalonia was alight with revolutionary fervour. After a failed coup d’etat against the left-wing Republican government, Spain had fallen into civil war and Barcelona into the hands of the anarchists.

Across the city, churches were targeted as decades of accumulated resentment against clerical authoritarianism was unleashed - and the revolutionaries made no exception for the strange, half-finished church on the north-eastern edge of town, the final masterpiece of an architect once revered in Barcelona.

Antoni Gaudí had been dead for more than a decade but his disciples were carefully carrying out his vision based on the many models and drawings he had left, and it was these that the radicals targeted.

On 20 July, members of the Iberian Anarchist Federation (FAI) came to the Sagrada Família and destroyed what they could. Drawings, photographs and letters were burnt, models were smashed, stones blocks destroyed, machinery vandalised and site buildings razed to the ground.

The militants returned later that day to dynamite the one facade that had been built already, but either failed or were talked down. Instead, they slung a banner between its two towers, advertising the Iberian Federation of Libertarian Youth.

And there it stood from that day on, the ruin of a dream already half a century old – the secrets of its design lost in a mess of plaster and acrid smoke.

>> Click here to read the full story

‘A nightclub on a massive Scale’: Touring Populous’ £365m Co-op Live arena

Soon to be the UK’s biggest indoor music venue when it opens in April, the 23,500-seat Manchester behemoth is an impressive site

“The brief,” says a member of Co-op Group’s PR team, looking out over the cavernous innards of what will soon be the UK’s biggest music venue, “was to create a sweaty nightclub on a grand scale.”

This might not be the first thing you would associate with the firm best known for its medium-sized supermarkets, but the £365m Co-op Live arena, designed by Populous and built by Bam, looks like it should be up to the job.

Vast, dark and filled with endless bars and elaborate light installations, it is set to become the UK live music industry’s hot ticket for 2024 when it opens at the end of April. It has already booked some of the world’s biggest acts for its opening month, from Nicki Minaj to Eric Clapton, Take That and the Eagles. This is to be expected. Tim Leiweke, chief executive of its US developer Oak View Group, has specifically set out to create the “best venue in Europe”.

>> Click here to read the full story

Why the industry needs another net zero carbon buildings standard

David Partridge has been tasked with bringing together construction’s many and varied definitions of net zero. He talks about why setting a recognised and easily understood benchmark for whole-life carbon emissions is so important

David Partridge shows me a slide to demonstrate why the industry needs another net zero carbon buildings standard (NZCBS). The slide has 15 different industry definitions of net zero.

There is LETI’s climate emergency design guide, the RICS whole life carbon assessment for the built environment, guidance for a net zero National Health Service, the RIBA 2030 climate challenge, NABERS and the UKGBC’s NZC building verification to name a few.

“I was speaking to an architect at one of our engagement sessions who said he spent the first six months of any discussion with clients understanding what their definition of net zero was before he could even begin designing the building,” Partridge, the chair of developer Related Argent, says.

The problem with this proliferation of net zero carbon definitions is that they are all tackling different aspects of the same thing. NABERS only covers operational carbon, RICS is a whole-life carbon assessment methodology but does not include any targets, RIBA and LETI have targets but these only cover residential, office, retail and education.

Partridge says the industry is “crying out” for a single standard that covers embodied and operational carbon and applies to all building types. This is why he has opted to chair the group developing the UK net zero carbon building standard which aims to develop that unified measure.

>> Click here to read the full story

Faster, better and less disruptive: the next chapter in Mace’s manufacturing journey

The contractor wants to bring DfMA discipline to high-rise residential projects for the same cost as traditional build. Building goes to London Bridge to see the third iteration of its high-rise system

With average margins somewhere below 5%, how to improve construction efficiency is contracting’s biggest challenge. Greater standardisation, offsite manufacturing and digital management of the construction process is recognised as the solution, but implementation strategies vary.

Laing O’Rourke stands alone with an in-house manufacturing facility but competitors have steered clear because the upfront investment and need to keep a factory working flat out to provide a return is seen as too expensive and risky. Instead, most rely on their supply chains to invest in manufacturing facilities and concentrate on streamlining site processes to drive efficiency.

The downside is that the contractor does not have complete control and visibility of the design, manufacture and delivery of the components, which limits the effectiveness of the project management process.

Mace has been developing a standardised approach to high-rise residential construction that leverages its supply chain manufacturing capability, therefore avoiding the cost of a factory yet giving it similar advantages to owning one. The objective was to cut the programme by 25%, vehicle movements by 40% and construction waste by 70%.

>> Click here to read the full story

British Land’s resurrection of Norton Folgate

Blossom Street was the focus of one of the most vitriolic London planning battles in recent years. But British Land has confounded the fears of Spitalfields residents by sensitively restoring many of the old buildings and mitigating the visual impact of new-build elements

Robust opposition to large developments is to be expected at times, but few disputes have been as acrimonious as the battle over British Land’s proposals to redevelop a network of semi-derelict streets on the edge of the City of London.

The principally commercial scheme is located on the edge of Spitalfields on the border with the City of London and, nearly 10 years after the first planning application was submitted, it is being readied for the first occupiers.

Called Blossom Street during planning and now named Norton Folgate, the scheme is a collection of sensitively and painstakingly restored Georgian, Victorian and Edwardian buildings with a couple of new-build, medium-rise blocks set back from the street edge at the northern end of the site next to the railway lines running into Liverpool Street station.

>> Click here to read the full story

Hinkley Point C: Building Britain’s first nuclear reactor in 30 years

Like its Finnish and French twins, Hinkley Point C has suffered from cost overuns and delays. What are the team doing to claw back the losses and what does this mean for Sizewell C?

Nothing on the drive from Taunton to Hinkley Point C hints at the scale of the project at the destination. The journey is along picturesque minor roads, through woods and up and down steep-sided, intimate valleys before the terrain flattens out to reveal Europe’s largest construction site.

The huge location, which is deliberately situated miles away from major population centres, sprawls across a flat plain next to the Bristol Channel on the Somerset coast. Everything about this project is supersized.

There are 58 cranes on this job, one of which is Big Carl, the world’s largest land-based crane. Powered by 12 engines and rolling on 96 wheels, this monster can lift 5,000 tonnes and needs dedicated tracks to move it to the different parts of the nuclear island, where the reactors are being built.

A dedicated bus company was set up to avoid thousands of workers clogging up the lanes with traffic. It brings up to 11,000 of them from around the area and home again on a fleet of 176 buses. This includes a route to transport people around the 176-hectare site. The site even has a doctor’s surgery, a fire service and police station.

>> Click here to read the full story

From the ground up: Ackroyd Lowrie on a mission to turn school leavers into architects with real work experience

With a focus on innovation and access, the east London studio is leading the charge in the architectural education revolution. Here’s how they are helping a new generation of architects to design the cities of tomorrow

Architects operate within a fast-changing industry, with constant pressure to deliver more for less. At the same time, societal changes are requiring the profession to focus increasingly on access, with expectations that employers provide opportunities to people who might previously never have considered a career in architecture.

How should architects respond? And how far can a single practice go in actively addressing the huge range of demands to deliver faster, better, and more diverse outcomes for clients and staff?

Founded in 2016, Ackroyd Lowrie has developed a reputation for delivering thoughtful, people-centred architecture that prioritises sustainability. The work spans a range of sectors, from residential developments and neighbourhood masterplans to commercial spaces and educational facilities. The practice is also branching out into property development, with a major housing scheme recently approved in Harlow.

Leading the practice are Jon Ackroyd and Oliver Lowrie, who bring substantial experience and a shared commitment to innovation and outreach. The two met while working together at Architype, a practice widely recognised for its commitment to Passivhaus standards and net zero.

>> Click here to read the full story

Championing sustainability: How Paris 2024 is reshaping the future of the Olympics

The Paris Olympics is embracing an approach pioneered by London in 2012 and taken to the next level, utilising existing venues and temporary structures as much as possible

The Games of the XXXIII Olympiad, starting in Paris this month, marks the end of an architectural era. Largely gone are the starchitects and quintessentially French grands projets. And in their place are existing and temporary venues.

London 2012 pioneered the use of temporary venues but was still dominated by a new stadium and Olympic Park in east London. Even the last games in Tokyo, in 2020, had a landmark new stadium – not untypically marred by controversy when Zaha Hadid’s design was dropped as too expensive and replaced by another designed by Kengo Kuma.

This time, however, the Stade de France, built to host the 1998 football World Cup, will be pressed into action as the main Olympic venue. It is a reflection of how far, arguably, the world’s biggest sporting event has moved towards more flexible and sustainable venues.

>> Click here to read the full story

1 Readers' comment