Reports out this week warn of five more years of economic decline, soaring unemployment and the threat of widespread social unrest. Could we be experiencing a second Great Depression? Building travels back in time to predict construction’s future

The suggestion that we could be in the midst of a global depression is a dramatic one. The words take us back to a time of mass poverty almost inconceivable to us now in the 21st century. The 1929 Wall Street Crash and the subsequent Great Depression threw 13 million US citizens into unemployment. In 1932 alone, 270,000 families were evicted from their homes and forced to live in shanty towns. Here in the UK unemployment figures in some cities hit 70% by the mid-thirties, leaving millions of families destitute and homeless. Their only option was to queue for food at soup kitchens and an estimated 25% of the population suffered from malnutrition.

Photographs from this period in history show scenes of people carting money around in wheelbarrows and heating their homes by burning wads of bank notes that had become worthless due to unimaginably rapid inflation.

While there is little question that the current global economy is in extremely poor shape, can a comparison really be drawn between now and the thirties? This week, research by the Institute for Public Policy Research warned that the economy would not return to pre-recession levels for at least five years, making any recovery slower than the one that followed that Great Depression. The International Labour Organization published a report on the same day predicting soaring unemployment figures and social unrest, stating, once again, that it would be another five years before a return to pre-2008 levels.

The big question, then, is whether these figures and predictions point to a period of depression comparable to, and even longer than, that in the thirties. And, more specifically for the construction industry, what the impact will be of a long period of unemployment and economic stagnation.

Nobody is in any doubt that the sector will look very different on the other side of the global financial and economic crisis, but economist Brian Green says the one silver lining of living and working through another depression is that lessons can be learned from the past that could help the industry work out what might be around the corner this time.

Before examining these potential emerging patterns, we consider exactly how a depression, as opposed to a recession, is defined and whether we are in the depths of one right now.

What is a depression?

The official definition of a depression is a 10% decline in GDP. In the UK the figure currently stands at 7.1%, which means that we are not officially in a period of depression. However, the GDP drop in 1929 was only 8%, which somewhat undermine the usefulness of the official definition. Green says: “It is easy to link the notion of depression to soup kitchen queues. But while recessions are the period of decline, depressions can be defined as the period from the start of a recession to when output reaches its initial level. Make no mistake, this is a depression of some order.

“In the autumn of 1933, our great grandparents were as far into their depression as we are into ours now. But there was a marked difference. Economic activity was accelerating on the back of a housing boom and the depression would be over by Christmas. We will not be so lucky. There are likely to be two more years of sluggish growth before GDP returns to its former level. Construction companies are preparing for a tough 2012 and, most likely, another period of cuts and contraction.”

Martin Wolf, chief economic commentator at the Financial Times, adds: “The UK is in the midst of what is set to be the longest - and most costly - of its depressions in over a century. The characteristics of this depression, compared with its predecessors, are the frightening weakness of the recovery phase.”

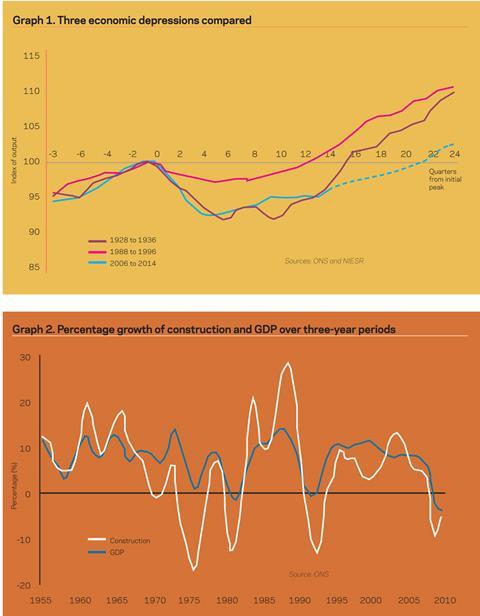

Graph 1 (below) plots the level of output for the three last depressions, by quarters starting from the first quarter of recession. Green explains the patterns: “What we see is that the nineties’ recession, the one most managers in construction will have experienced, was far shallower and shorter lived. It took about three years for the level of output to recover to its pre-recessionary level.

“This depression has followed a path broadly similar to that of the thirties’ depression, falling very sharply in the initial recessionary phase. The recovery came slightly sooner, much helped by the fiscal and monetary stimulus, but growth in the recovery phase seems to be much less vigorous than it was in the thirties, when a housing boom helped propel economic activity.

“The dotted line shows the expected path of the recovery on the basis of the consensus of independent forecasts published by the Treasury. These suggest a much longer depression this time around, and, worryingly, there is a more than even chance that these forecasts will be revised down. That would mean an even longer period of depression.”

Impact on construction

Such a bleak outlook will inevitably have an impact on a construction industry that is already suffering huge public sector cuts and increased competition for private work. Soaring unemployment and at least five more years of challenging times to come has focused industry figures on finding strategies to prepare for the worst.

Iain Parker, head of offices at Davis Langdon, says: “I do actually get really quite concerned when I think about it properly. It’s going to be a long stretch from now, possibly over the next five years, before there is a proper recovery. This period will be a key moment in history and I think we’ll all look back in 15 or 20 years time and say: ‘My God, that was a really awful, tough time’. The result is that a whole number of things will need to change, from commercial office space through to residential design.”

“I don’t think anyone is under the impression that this economic downturn will be over in 10 minutes,” adds Land Securities retail project director Derek Baillie. “Survival will come down to knowing your sector. In retail that will be about being the quickest on your feet that you can be as this sector is changing so fast. With residential, it will be about pitching for the right market. You have to offer really good value for money in the current climate.”

Construction will need to adapt to match the new patterns of production, service delivery and lifestyles that will inevitably emerge as a result of the economic turmoil. The recession of the nineties (see graph 2), created a huge shift in the UK economy from production to services. This radically altered the proportion of commercial, industrial and residential building within the mix of construction projects. There was far less need for industrial buildings such as factories as a result of the social shift to commercial work.

The future of construction this time around will be affected by IT and lack of earnings growth. Computing technology, broadband and mobile devices allow for far greater flexibility over when and where people work. After several years of frozen salaries, employers could now choose to increase pay to keep staff rather than invest in physical office spaces. A housebuilders salary survey last month revealed that, for the first time in three years, salaries are starting to rise and staff are starting to approach recruitment companies with interest in alternative roles. Employers are under pressure to offer their employees more competitive packages if they want to keep their best staff: “Tough commercial pressure will force firms, especially those in the services sector, to squeeze spending on offices, most likely by looking at the opportunities technology presents for more out-of-office working and hot desking,” says Green.

Davis Langdon’s Parker confirms this: “We are about to have 300 more people coming into our existing office space as Davis Langdon and Aecom and we have developed a strategy to encourage more people to work from home and a hot desking system rather than try to accommodate everyone at once.”

These factors combined are likely to promote a rise in the construction of pay-as-you-use offices dotted across the country. This will bring its own opportunities for construction in the residential sector: “It’s not true that to work from home you just need a spare room and a cable,” says Robert Adam of Adam Architecture. “It’s more complicated than that and people need more tailored spaces to make it work properly. We just designed a development in the West Country where 50% of properties had external entrances to a separate area or studio, usually above the garage. We can do this now, work flexibly, on the go and in a very mobile way. And I am convinced it will change the way offices and homes are designed and built.”

The way we shop

Retail is another sector likely to be affected by the social and economic changes and this too will have an impact on construction. The squeeze consumers are currently feeling will inevitably affect shopping patterns and with them the shops we build. We should expect to see shops become smaller and, in some cases, disappear altogether in favour of purely online stores. Construction’s role will therefore shift from building retail to transforming existing stock.

Land Securities’ Baillie says: “The retail sector is changing so fast that retailers themselves don’t know what’s around the corner. So our strategy has been to invest more at the start to incorporate flexibility. We start off our projects with just a plain box design. The retailer will then come along and will most likely say: ‘That was fine a year ago but now we need x, y and z’.

“More tangible changes we’re noticing at the moment as a result of the internet shopping boom are department stores being smaller as there is less need for large storage areas. The click-and-collect system means that products can be stored in warehouses. And this is where opportunities might arise in the future as warehouses are built out of the centre of towns to be used by a number of different retailers at one time. It’s about adapting the existing stock and adding to it in ways that will make it more efficient, not starting from scratch on every scheme.”

Adapting to a new order

There is no doubt the next few years will be tough and that the impact of the economic and financial crisis will spark a series of changes in social behaviour that will, in turn, impact on the construction industry. But does this equate to a depression? The lack of any solid definition of the word and the longevity of the downturn suggests it would not be an entirely misplaced term. Even Sir Mervyn King, governor of the Bank of England, said last month that we were in the midst of the worst ever financial crisis.

Whatever terminology we use we appear to be heading towards the toughest, slowest and most painful crawl towards recovery in modern history. It is likely that the construction industry will be pressed increasingly to reshape the nation’s estate to support a much changed economic and business environment. For some it could

also be an opportunity to identify new needs and use them to win work. For others who can’t or won’t adapt, the future really does look depressing.

How the Great Depression changed the way we live

- A new look in women’s fashion emerged in the thirties. In response to the economic crisis, designers created more affordable fashions with longer hemlines, slim waistlines, lower heels, and less makeup. Accessories became more important as they created the impression of a “new” look .

- The board game Monopoly, which first became available in 1935, was immensely popular perhaps because players could pretend to become rich.

- In the US, a number of great structures, including the Empire State Building and the Golden Gate Bridge, were completed during the Great Depression, providing jobs to the unemployed.

No comments yet