Michael Gove may want free schools to succeed but his department won’t be throwing much money their way. So are these cut-price schools up to the job or doomed to become places for kids to fail in?

This month 109 new free schools will open their doors to pupils for the first time. Together with the 81 already open, and the 102 already approved by education secretary Michael Gove to open in 2014, there are now just shy of 300 of the new locally led independent schools either in place or in the pipeline - with many more still seeking government approval. Gove has made the schools, which are independent of local authority control and can be led by parents, teachers or private groups, a centrepiece of his education policy - responding, he says, to local need and parent dissatisfaction with failing or coasting state schools.

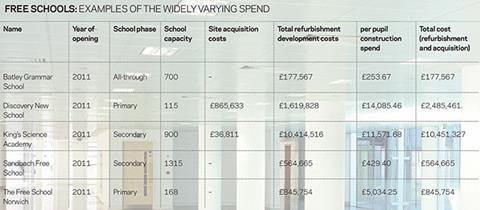

But unlike flagship government initiatives since time immemorial this experiment with a new form of education has not had money thrown at it. There is no specific capital programme for free schools - funds to set up premises can be taken from a variety of programmes, including £982m set aside by chancellor George Osborne in last year’s Autumn Statement for free schools and academies. Gove has made clear that he believes it is quality of teaching, not the school environment, that is the key to effective learning, so free schools will see no lavishing of public cash on expensive buildings. The days of the Building Schools for the Future (BSF) programme, in which up to £35m was spent on individual schools, are long gone.

Given these limited resources - the average construction cost for the 23 schools that have reported back is just over £3m - most are not being set up in purpose-built premises. All observers accept that the majority are re-using existing buildings. Buildings of all kinds are being converted - offices, warehouses, disused mills, old schools, housing blocks, fire stations, even a church crypt and a job centre. But these buildings and their limited conversion budgets are starting to prompt concern. Can these buildings really be made appropriate for teaching in? Or is there a risk that cut-price education now is storing up problems - and costs - for the future?

Meeting basic standards

According to many of those involved in the programme all the problems involved can – and are - being overcome. Chris Bowmer is associate director at Gleeds, which is on the Education Funding Agency’s (EFA) free schools consultants’ framework, and has worked on a range of projects. “Whether you accept this [standard of school] entirely depends upon your aspiration. Times have undoubtedly changed since BSF. But these free schools meet basic standards.” Likewise John Frankiewicz, chief executive of Willmott Dixon Capital Works, which he says has won between £50m-£70m of work on free schools, says that while compromises are inevitably made when using existing buildings, all the work is done to a good standard. “You might prefer a new build, but this doesn’t mean the standard of work done on the refurbs is any worse.”

Essentially this is Gove’s position - these schools may not be flashy, but they hit basic standards and are the better for being led by, and responsive to, local demand.

But look below the surface and there are those who see a darker side to the government’s implementation of austerity education. John Jenkins is a founding partner of Haverstock, which is working on a number of free schools, advising both clients and contractors.

“There is a significant problem in my view. It is very difficult to find appropriate buildings, and then the funding is simply not adequate, both for the appropriate upgrading of the fabric, and repairs. We are creating an ongoing maintenance burden that is storing up problems for the future.” Jenkins has a long list of issues with the current crop of buildings, and he is not alone in his concerns.

First find your building

The first difficulty facing free schools is in securing appropriate buildings. With Gove having staked a large amount of political capital on making free schools a success, those involved in the process report pressure from the department to find premises quickly. One architect, who declined to be named, said: “Those close to the department say they can’t believe the pressure they’re under to get schools out. It’s almost as if they see anything with four legs and standing, then sign it off.”

While there is no evidence the department is exerting undue or unfair pressure, it is widely accepted that locating reasonable premises to convert is a major difficulty for free schools - particularly in high demand areas such as London, and particularly for secondary schools, which commonly house 800-1,000 pupils. Natalie Evans, director of the New Schools Network, says: “Securing sites and associated planning issues remain the single largest challenge for free schools. Even once groups have found a site, councils that are not supportive can - and do - use the planning system to delay progress.”

The previous application [of space standards] was too inflexible, but this is a case of the pendulum swinging too far the other way. The standard is so low, basically any old crap is allowed

Roger Hawkins, Hawkins\Brown

Jenkins says this is leading to sites being chosen that are a significant distance from the communities they are designed for. In addition, he says buildings are sometimes being chosen without basic feasibility studies being undertaken, despite the fact these would cost just £5,000-10,000. In general, Jenkins says there is a problem of inexpert clients getting into trouble through naivety. For example, he says, the department is offering little help or funding for curriculum analysis for free schools - a basic analysis that allows them to determine what the requirement for premises needs to be.

Jenkins says: “I have worked with one school where only very late on did the people running it realise there was virtually no outdoor play space. And they suddenly had to think ‘what happens when 800 children need a break time?’ There was no money at that point for any innovative solutions to get round it, such as putting the playground on the roof.”

That school is not due to open this term, and it is understood that the situation is ongoing.

It is not in question that set-up costs for free schools are being driven down. The Department for Education (DfE) told Building in a statement that the capital funding provided for each project is “dependent on the requirements of the school, whilst ensuring value for money at every step. We always look to drive down costs wherever possible.”

But for all other schools the desire to drive down costs is balanced against detailed standards the schools are required to meet. The department has a schedule of accommodation which sets basic room requirements and class sizes, and a facilities output specification which covers everything from energy efficiency, daylighting, acceptable building materials and acoustics. New builds also benefit from baseline designs.

However, industry sources say free schools are deliberately exempt from the schedule of accommodation in order to give their promoters the freedom to design the accommodation around their educational concept. Furthermore, the same sources say refurbishment projects escape the requirements of the facilities output specification because of their complexity, meaning free schools that are refurbishments - the vast majority - don’t meet these specs either.

The DfE said in a statement that free schools have to comply with “all relevant statutory and regulatory requirements, including the department’s school premises regulations,” without specifying what those are for refurbishment projects. But even supporters of the programme, such as Bowmer, recognise the standards are lower: “Yes, it’s basic - we get the ventilation and acoustics right, and the decoration, and we’re pretty much there. We try and do as much as we can, but in reality it’s a much lower standard. But it doesn’t mean they’re not decent,” he says.

Roger Hawkins, founder at architect Hawkins\Brown, which is also working on free schools, is less sanguine: “Yes, some have done fantastic things. But there are also some really shocking examples. Building Regulations are pretty low down the agenda.”

So what does this lack of a clear standard mean in practice? One consultant on the government’s framework, who declined to be named, says the spend in some schools has been as low as £100-200/m2 , compared to £1,500/m2 for new build. “It’s a lick of paint and change the light fittings in some instances, that kind of spend.”

Sub-standard schools for the future

The problems arise when this lack of funding stops promoters from addressing more fundamental issues which have the potential to affect learning. Many buildings such as offices, forexample, have grids of columns between floors which don’t necessarily suit the size of classrooms required. Under current EFA standards, a 30-child secondary classroom should be 55m2, already lower than the previous BSF standard. But if this doesn’t fit the layout of the existing building, then promoters are left with a choice between smaller classrooms, or classrooms with pillars running down the middle of them. Jenkins says: “It’s a free for all, so we’re having to explain [to a promoter] why a 45m2 classroom won’t work. There’s been so much work done over the years as to why this is important - it’s crazy we’re having to rehearse these arguments again.” Consequently, he says, he is seeing some teaching spaces with columns in the middle of them.

As difficult as he says that kind of obstruction makes teaching, more serious, he says, is that skimping on construction work is affecting the basic environmental qualities of a room: its heating, daylight, ventilation and acoustics. “What we’re going to have is kids falling asleep in the afternoon because there’s too much CO2 in their classroom because there’s not enough ventilation. Or kids who can’t hear their teacher because the building is too close to the trainline without acoustic measures being undertaken.

“Our experience is that the environment has a direct impact upon learning. A brilliant teacher can teach almost anywhere, but not all teachers are that good, they need all the help they can get from the environment they work in,” he says.

So severe are these concerns that both Jenkins and Hawkins claim they know of practices that have walked away from commissions to avoid being associated with the end product. Many would say these practices are just being idealists who are failing to realise the world has changed since BSF. But the critics reject this. “I actually had some sympathy with the government’s case for relaxing space standards,” says Hawkins, “because the previous application was too inflexible in some cases, writing off perfectly good schools. But this is a case of the pendulum having swung far too far the other way. The standard is so low, basically any old crap is allowed.”

Clearly some promoters - often those who are already behind existing academies so have some experience of running a school and procuring construction - are making a success with limited taxpayer cash, and meeting a basic need for school places at the same time. But a desire for efficiency, and the industry’s desire for this steady flow of work, shouldn’t become an excuse for allowing a generation of children to be taught in sub-standard schools.

Read Richard Hyams of Astudio on designing for new-build free schools here

No comments yet