Ripping the guts out of the RSC’s Stratford-upon-Avon theatre and building a new auditorium in the existing one was Bennetts Associates’ bold remedy to the many poetic injustices being done to the Bard

For the past 75 years the work of the world’s most famous playwright has been performed by the country’s leading classical theatre company in what amounts to an old cinema. Although it was purpose built in the thirties, this theatre in the heart of Stratford-upon-Avon was designed by Elizabeth Scott when cinemas were all the rage.

The problem is that this building type is doesn’t work well as a theatre because the audience is too far from the stage. This is the antithesis of Shakespeare productions, where audiences have traditionally been close to the action. According to Peter Wilson, the RSC’s project director, this is harming the RSC. “It’s becoming increasingly difficult to attract top actors and directors here,” he says.

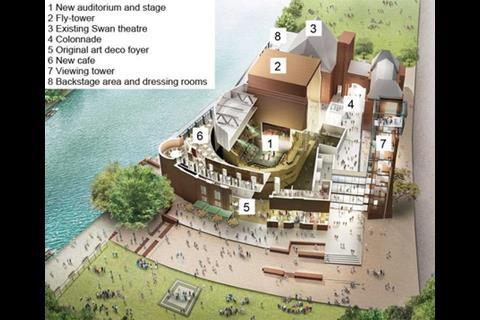

The problems extend beyond the main auditorium to the whole complex, which Wilson describes as a “huge muddle of ad hoc spaces”. For example, there is a second, Victorian auditorium back-to-back with the main one, both sharing the same backstage space. This gave rise to lots of (unfortunately apocryphal) stories about Macbeth turning up in the middle of Hamlet’s soliloquy.

A cafe was added shortly after the theatre was finished, completely blocking views over the Avon. At the end of the nineties, the RSC tried to improve the situation by appointing architect Erick van Egeraat, who promptly suggested flattening the whole thing and starting again. Cue howls of protest from Stratford-upon-Avon locals and English Heritage, which ensured the plan was quickly dropped.

In 2004 architect Bennetts Associates was engaged to try again. The challenge was to come up with a functional, aesthetically pleasing solution that satisfied the RSC, the locals and conservationists. The challenge for contractor Mace was making sure the scheme went to the script. “Every theatre I can think of has been six months late and vastly over budget,” says Tim Court, project director for Mace. “There was tremendous pressure on me to bring this in time and on budget.”

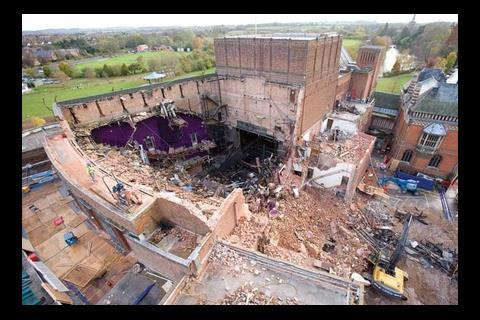

Bennetts’ answer was to rip the guts out of the thirties theatre and build an auditorium inside its facade. This has a “thrust” stage that protrudes into the audience to make them feel closer to the action. Also, the furthermost seat from the stage is just 15m, rather than the 27m in the old building. An exterior colonnade linking the theatre’s two performance spaces is being added, the old cafe has been knocked down and actors will have new dressing rooms. A viewing tower has been built with the idea of more closely integrating the theatre into Stratford, which gets 3 million visitors a year. The RSC wants more of these people to visit the theatre even if this only means using it as a place to get a good view of the town.

Court says delivering theatres is particularly challenging because there are so many stakeholders, each with their own requirements. For example, theatre technicians want the biggest and best kit and to buy it as late as possible so it’s as up to date as possible, but Mace needs to know the costs early on. There are also the constant changes to cope with, everyone from wigmakers to the bar staff. “They see it on-site and say: Oh, I didn’t realise, I’ve got to be able to get a trolley through that door,” says Court.

But Court’s biggest challenge has been dealing with the unknowns that refurbishments always throw up. The original design drawings were available but did not show the theatre in the built state. In an effort to keep costs under control the building was constantly surveyed during the demolition phase so Mace could give the specialist contractors a clear idea of what to expect. Court says this meant he got fixed prices for 80% of each package for the substructure, structural steel and builders’ work packages, rather than the more normal figure for refurbishments, which is about 50%.

The roof and interior of the old theatre was scooped out by demolition contractor DSM. Space meant long-reach equipment could not be used for demolition but DSM still managed to finish on time. However, this proved to be a honeymoon: once Mace moved on to the next phase of the job it ran into a large, unexpected problem centring on the basement under the new stage. Because the new theatre is smaller than the original, the thrust stage is being constructed in front of the old stage, which also had a basement.

“It had to be deep enough to conceal someone sitting on a throne on a scenic lift with a crown on their head,” says Wilson. This translates to a finished depth of 7m. He says the team “agonised” over the depth of the basement because of the cost but decided to go for it because it would be impossible to make it deeper later.

Old drawings showed that the sides of the basement under the original stage were retained by steel sheet piles. The new basement sits next door to this and is formed by sinking a ring of retaining piles around the basement perimeter (secant piles), scooping out the earth, then forming the basement slab. But things did not turn out as shown on the original drawing.

“As soon as we started piling near the existing basement we hit a mass of concrete and steel,” says Court. “We found the steelwork for the original basement extended 2m further into the new basement. It meant digging through 8m of concrete and steel, which would seriously interrupt our programme.”

An added complication was the high water table – the river Avon is next to the building. “It meant we had a cofferdam only on three sides of the basement so water was pouring in through the steel and concrete,” says Court. Mace had to try to fill in the fissures in the concrete and steel with grout, as well as drilling through the whole lot and injecting grout to stop the water coming in. “It stopped the water sufficiently to allow us to carry on,” says Court. The problems with the basement added seven weeks to this part of the job.

The new concrete auditorium structure was built inside the original theatre walls as planned because it was several metres away from the basement. But the continuing work to the basement threatened to delay work on the roof structure and internal steelwork. Clearly, working over the basement would be dangerous, and once the roof structure was in place the internal steelwork had to be brought into the auditorium through the sides of the stage exactly where the basement was located.

The solution was to install a crash deck over the basement. This meant work could continue in the substructure, the underside of the roof structure, and then the internal steelwork that supported the seating and the technical deck just under the roof. Despite this the whole programme has had to be rejigged and Court says he is still in programme recovery a year after the problem was found.

Elsewhere the job, although complex, has gone relatively smoothly. The viewing tower presented its own challenges (see box) and the RSC’s desire to leave the old bits of the building, including graffiti, exactly as they were caused some raised eyebrows.

“It’s quite a shock to us to leave stuff unfinished,” says Court. “The guys want to do things perfectly and can’t understand it has to be left as it is. But once they got used to the idea they were quite proud of it.”

He adds that they also enjoyed the job, and that Wilson has made a big effort to make workers feel valued, even hosting barbecues and pig roasts. And as this is the RSC, treats have included performances in the temporary theatre nearby and drinks with the cast.

“We found they got on really well and it means the cast and production teams get to know what’s involved in construction – and they understand why they can’t have their building back in five minutes says Wilson. Court reckons it has made a difference to the quality of the job, too. “The guys say they have never been on a site where they’ve had this sort of treatment. They really like coming here, there is a genuine enthusiasm,” he says. “You make a little more effort because it shows the client really cares about you.”

Building the tower

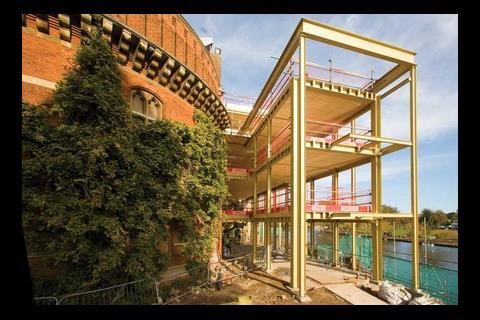

While the work on the main theatre was under way, the project team also tackled the most visible part of the job: Bennetts Associates’ viewing tower.

This sits to one side of the theatre and provides vertical circulation inside the main auditorium by means of a series of link bridges. Bennetts Associates wanted the tower to be constructed with load-bearing brick walls rather than just a brick skin. “It gives the building a character it wouldn’t have if it was just cladding on a frame because you can see the thickness of the walls,” says Simon Erridge, the project architect.

But ordinary bricks would not do because the ones at the base would by crushed by the weight of the 36m high tower. This meant Mace needed the strength of an engineering brick, but it also had to be handmade. As this is not the sort of thing normally available, Mace found a company in the Forest of Dean called Coleford who could specially make the bricks for the tower.

Work kicked off on the brickwork in January but the bricklayers soon hit a snag. As engineering bricks are not absorbent, the mortar between them stayed wet and sloppy far longer than it would with ordinary bricks.

“We found we were limited to the number of courses we could do in a day without the mortar being squeezed out,” says Court, adding that the bricklayers could do only about 10 courses a day. “It took us nine months to do the tower brickwork.”

Setting out the brickwork was also challenging because the tower slopes towards the top at an angle of 3º. The tower’s concrete core was already in place but the bricklayers could not measure out from this because standard concrete tolerances are not tight enough. The answer was to fix a metal grid to the top of the core and stretch piano wire from this down to the ground, where the bricks would have to be placed.

A metal staircase sits between the core and the brick wall. Sections of stair had to be added as the brickwork went up to get it in. “Every few weeks we had to swing the piano wires out of the way to get the stairs in,” says Court. “Yo’ud think in this day and age there would be a better way of doing it but there isn’t.”

Again time had to be made up. The tower has a steel and glass viewing box at the top.To save time, and to make the job safer, the box was prefabricated on the ground while the tower was being built and craned into position at the end. A big template of the fixing positions at the top of the tower was made to ensure it would slot neatly into place. The steel frame was lifted up first then precast cladding panels with a brick facing were craned in.

Weight watchers

In this new-meets-old job, original walls are inevitably supporting new structures. For example the thirties auditorium walls partially support the floors inserted in the space between these and the new concrete auditorium. The old fly-tower walls also help support the new dressing room block next door. The original block, which has been replaced, was three storeys. The architect wanted to add another but the fly-tower couldn’t take the weight.

Structural engineer Buro Happold found a potentially neat solution in the form of laminated timber planks. These are just 265mm thick and can span up to 7m. “By replacing the original concrete slabs with something lighter we could add an extra floor without needing to strengthen the original structure,” says structural engineer Andrew Wylie.

But laminated timber planks had never been used for this application in the UK before, so the team was understandably cautious. Court was concerned that the timber “slabs” would be exposed to the elements for a whole winter before the roof went on, and rain would cause the wood to swell and delaminate. He did consider wrapping the planks in plastic to protect them but the only way to be sure this would work was to try it out.

“We got the company to deliver a large piece and left it outside for six months to see what would happen to it,” says Court. “It was absolutely fine so we knew the best way of preserving it was to leave it as it is without encapsulating it in plastic.”

Buoyed by the success of the experiment, the planking has been used for all the new floors apart from two technical areas connected to the roof, which needed to be particularly stiff.

Court likes the planks, saying they are quick to put up and come with pre-routed service runs. Another advantage is that holes can be cut without needing to consult a structural engineer. The only problem is that the design has to be finalised before the planks are made. The planks are expensive but Wylie thinks the overall costs compare favourably with traditional alternatives. “If you compared the costs directly with, say, precast concrete planks, you wouldn’t go near it,” he says. “But factor in all the other issues like the saving on foundations and speed of construction it comes out very well.”

Project team

Client Royal Shakespeare Company

Architect Bennetts Associates

Engineer and transport consultant Buro Happold

Theatre consultant Charcoalblue

Access consultant David Bonnett Associates

Project manager Drivers Jonas

Construction manager Mace

Cost consultant Gardiner and Theobald

Acoustic engineer Acoustic Dimensions

Contractors details

Temporary accommodation Hewden Stuart

Temporary electrics and plumbing Wingate Electrical

Cranage Select Plant Hire

Hoists Taylors Hoists

Scaffolding Sky Scaffolding

Setting out SES

Logistics Elliott Thomas

Demolition, soft strip and asbestos DSMPiling Cementation Foundations Skanska

Concrete sub and superstructure John Doyle Construction

Structural steelwork Billington Structural Steelwork

Curtain walling Deepdale Solutions

Specialist windows Crittall Windows

Zinc roof systems Varla (UK)

Flat roof systems M&J Flat Roofing

Brickwork and blockwork Lesterose Builders

Dry linings/plastering Fireclad

Builders work Shaylor Special Projects

Toilet and dressing room fit out Fireclad

Hard floor finishes Szerelmey

Soft floor finishes Loughton Contracts

General joinery Swift Horsman

Heritage joinery Taylor Made Joinery

Solid timber floors KLH UK Limited

Auditorium floors and staging Taylor Made Joinery

Architectural and general metalworkGlazzards

Auditorium metalwork CMF

Painting and decorating S Lucas

Auditorium seating Poltrona frau S.P.A

Mechanical services Rotary North West

Air systems Ductwork Wolverhampton

Controls AES Ltd

Electrical services Michael J Lonsdale

Theatre electrics Stage Electrics

Commissioning management Commtech

Lifts ThyssenKrupp Elevator UK

Under stage works Delstar Engineering

Over stage works Trekwerk

Security and CCTV Niscayah

Hard and soft landscaping Fitzgerald Contractors

Flood compensation Hasmead

No comments yet