The government has revived its interest in green construction, which had been taken firmly off the agenda. David Blackman reports on what form energy-efficiency experts think this revival could take and whether the strategy could simply be a lot of hot air

The eco-building fraternity is likely to be suspicious of the government’s recent volte-face on green construction outlined last month in the clean growth strategy.

This document, released by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), purports to put green building back on the agenda with new building energy efficiency targets (see highlights from the Clean Growth Strategy below). Its measures include a new goal that as many private rented homes should be upgraded to meet the band C energy performance certificate requirement by 2030 with the same ambition for all dwellings by 2035. The more than 200 documents published to accompany the strategy also include a call for evidence on incentives to encourage energy efficiency such as green mortgages.

However, it is only two years since the Conservative government, pumped up after its outright victory at the 2015 general election, scrapped a host of green building measures, including the once-flagship zero-carbon housing initiative. So, why has the government re-embraced the environmental agenda after dropping it like a stone such a short time ago? Can economic growth and decarbonisation work together and can the industry have faith that anything will come of discussing sustainable building this time around?

Why the about-turn?

A change in personnel helps to explain the change of tone. Recently named climate change and industry minister Claire Perry, who leads on the strategy, is a committed environmentalist. Her departmental secretary of state Greg Clark is happy to parade his credentials based on having helped former prime minister David Cameron to implement more environment-friendly policies in the Conservative Party during the late noughties.

But perhaps the biggest change has been the departure from government of Nick Timothy, Theresa May’s former joint Downing Street chief of staff, who once branded the Climate Change Act as a “monstrous act of self-harm” by the UK.

The Conservatives also have pressing electoral reasons to re-embrace the green agenda. A poll recently carried out by the Tory think tank

Bright Blue showed that climate change is ranked as the most important single issue by the 18 to 24-year-olds, a cohort that has deserted the party in droves since 2010.

“The Conservatives will never win another majority unless they attract young voters and one of the issues that those voters care about is climate change,” says John Alker, director of policy and places at the UK Green Building Council (UKGBC).

In addition, big business support for action on climate change has solidified since the signing of the Paris Agreement on climate change in 2015, despite president Donald Trump’s decision to pull the US out of the accord.

Meanwhile, evidence has been stacking up that growth need not be sacrificed in the push to decarbonise the economy. A study, published earlier this year by the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit think tank, showed that the UK had been more successful than any other G7 nation in decoupling emissions and economic growth over the past 25 years. And if anybody needed extra evidence, the plunging cost of generating offshore wind power in September’s renewable energy subsidy auctions provided it.

Nevertheless, the pace of the government’s about-turn has caught even close observers on the hop. Sophie Walker, UK head of sustainability at JLL, says: “I am surprised that the government has moved so much at pace on this, post-Brexit vote.”

“Energy efficiency felt like a poor relation – hopefully this is a sign that the tide is turning”

John Alker, UK Green Building Council

Alker says that it is a long time since the government has been so encouraging about decarbonising the economy. “For companies, there is a sense that this government means it, which is really helpful. It’s not a question of whether but how,” he says. “There is a lot of work still to do but it was a lot better than it could have been.”

The document’s focus on energy efficiency can be explained by broader trends in power generation. The UK looks set to exceed its climate change targets until deep into the next decade, largely thanks to the switch from coal-powered electricity generation to less heavily emitting sources of power, such as gas and renewables.

“We’ve been coasting along on energy supply system changes that have delivered on our early carbon budgets. Enough people have demonstrated to government that it’s not going to get us all the way,” says Joanne Wade, chief executive of the Association for the Conservation of Energy.

However, now that the proportion of electricity generated by coal has dwindled to negligible proportions, generating electricity will deliver diminishing emission reductions.

A heated issue

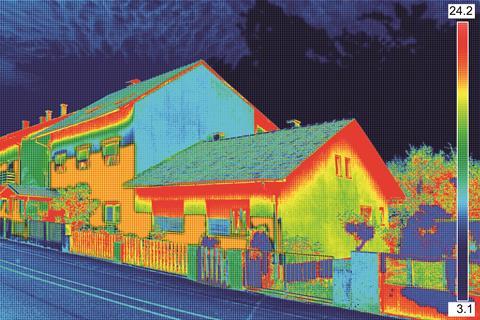

Heating from buildings, which is responsible for around one-third of all UK greenhouse gas emissions, is the next big decarbonisation challenge. The problem here, though, is that there is no clear path to phase out gas heating, which would need to happen in order for the UK to meet its carbon reduction targets.

Getting everybody to swap their gas boilers for electric central heating is technically feasible but would require a vast increase in generation capacity in order to satisfy peak time winter demand.

Wade says: “Decarbonising heat is not as straightforward as decarbonising electricity – there aren’t obvious options, so it’s concentrated the mind.” As a result, the focus has moved back to energy efficiency as the best hope for achieving the next big wave of carbon savings.

The spin-off benefit is that less leaky properties reduce the overall size of the decarbonised heating challenge. The added twist is the furore over energy bills, with the government seemingly accepting the argument of its statutory advisers at the Committee on Climate Change that energy efficiency is the best long-term solution for lowering household fuel costs.

It’s too early to detect in the strategy the outlines of a building retrofit scheme to replace the Green Deal, which proved such a flop until it was wound up two years ago.

Nevertheless, Alker says that it is a long time since the government has made so many encouraging noises about decarbonising the built environment. “Energy efficiency felt like a poor relation – hopefully this is a sign that the tide is turning,” says Alker.

Bevan Jones, managing director of Sustainable Homes, says it is good that decarbonisation of the built environment is “back on track” with the establishment of a trajectory for ensuring that decarbonising social and private rented housing by 2030 and performance certificates get back on track.

However, while the clean growth strategy points the UK to a greener destination, it is less clear about how the UK will get there.

Clean growth strategy

The clean growth strategy, which was published last month, is designed to outline how the government intends to meet its statutory carbon reduction targets in the Climate Change Act. The strategy specifically addresses the targets outlined in the so-called fifth carbon budgets, which states that the UK must reduce its emissions to 57% of 1990 levels by 2032.

The measures include:

- Extending the ECO (Energy Company Obligation) home energy efficiency improvements scheme from 2022 to 2028

- Phasing out during the 2020s the installation of oil and diesel heating in new and existing homes currently off the gas grid

- Aiming for “as many homes as possible” in the private rented sector to meet the Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) Band C by 2030 where “practical, cost-effective and affordable” with a similar aspiration for all residential properties by 2035

- Consultation on how social housing can meet EPC Band C by 2030

- Consultation on raising energy efficiency minimum standards for rented commercial buildings following the upcoming conclusion of the independent review of building regulations and fire safety

- Strengthening energy performance standards for new and existing homes under building regulations, including futureproofing new homes for low carbon heating systems

- Building and extending heat networks across the country, underpinned with public funding until 2021

- Exploring scope for further action on compliance and enforcement on energy performance, using data from smart meters.

Direction needed

“The obvious criticism is that it needs more detail. There is a lot of talk but not much specific on energy efficiency,” says Barny Evans, head of sustainable, places, energy and waste at engineer WSP.

Andrew Dixon, head of policy at the Federation of Master Builders, agrees: “The objectives are reasonably ambitious but there’s not a lot of flesh on the bones.” He identifies the treatment of owner-occupied housing as the biggest grey area in regard to energy efficiency. While private rented sector housing is expected to meet the EPC benchmark band C by 2030 where possible, owner occupied homes are not due to meet a similar standard until five years later. Meanwhile, big question marks remain over how home owners will be incentivised to upgrade their properties following the collapse of the Green Deal.

JLL’s Walker points out that it would be useful for the industry to be informed about direction of travel. “If we know where we are heading, we can invest early.”

The strategy is particularly woolly on new-build stock. The UKGBC’s Alker argues that zero-carbon housing needs to be back on the agenda as part of the review of building regulations commissioned following the Grenfell Tower disaster, the interim report on which is expected later this month. The UKGBC is pushing for all new housing to be net zero carbon emitting by 2030, extending across to the entire building stock by 2050. He argues that it is “madness” to be building stock that will have to be refurbished in 20 years because its energy performance isn’t up to scratch.

“At the moment, we are building properties that will have to be retrofitted, which is really not sensible,” agrees David Adams, technical director at Melius Homes, which is developing ultra-low emitting Energiesprong housing pioneered in the Netherlands.

Another concern is that the strategy is very long on consultation. As well as getting feedback on the document itself, it promises a plethora of consultation exercises on issues such as how to get social housing properties up to EPC band C by 2030 and minimum energy efficiency standards for rented commercial buildings. The document also heralds a number of calls for evidence, the most important of which relates to how to provide better incentives to encourage improved energy efficiency.

The last thing that the green building sector seems to want is more consultation, Adams says: “How many times do you need to ask people what you are doing? We need to get on and do something.” Jones agrees that the time for talking is over: “I’m not sure that we need more consultation on low-carbon building standards because we know what needs to be done.”

Convincing doubters

And the government will have its work cut out convincing those who have been marched up the zero-carbon homes hill and then back down again that this time it is serious. Wade at the Association for the Conservation of Energy says: “The industry is still keen to work with the government but they are nervous because they have had their fingers burned. We would like to see something very definite.”

Alker agrees that there must be a “quite substantially different set of policies on the table”, including minimum standards for private rented housing, a firm trajectory for decarbonising owner-occupied housing and fresh financial incentives for retrofit work to replace the scrapped (albeit unlamented) Green Deal.

But this will require the green message to be heard across Whitehall. “The concern is that there’s not much joined-up policy between the Department for Communities and Local Government and BEIS,” says Sustainable Homes’ Jones.

Alker doubts that when the volume housebuilders piled into Number 10 Downing Street last month to discuss housing delivery, green building was on the agenda.

“Housing policy can’t be treated separately to the clean growth strategy. There is a slight danger that [the government] considers this a green box to be ticked, but this needs to weave through all aspects of housing and industrial strategy.”

“It’s a good start, but there is still some way to go for this to be genuinely embedded across all government departments,” he says, adding that the acid test for the government is whether it is willing to use stamp duty to encourage homeowners to upgrade their homes.

Adams, who is a former director of the defunct Zero Carbon Hub, worries that government remains wedded to fears that higher green building standards will hurt housing supply, increasingly its overriding priority.

“They think it’s a zero-sum game and that more regulation equals less homes. There is no evidence for that – they can do both.”

Wade suggests that ministers could demonstrate their bona fide green credentials by allocating a pot of money in the Budget later this month to pump prime a regional pilot of stamp duty rebates for householders who have upgraded their homes.

Wade says: “The top-level messages were good – now we have to make it happen. The next six months is going to be crucial as to whether it is remembered as a good document or hot air.”

The government will need more than warm words to demonstrate to construction that it is serious about tackling the heating planet.

No comments yet