Busted budgets, poor planning and co-ordination, horrendous delays, cancelled transport schemes, laborious bureaucracy, corruption, mass protests and onsite fatalities - apart from that, preparations for the 2014 World Cup seem to have gone very smoothly

When fans tune in on 14 June to see England play Italy in its 2014 World Cup debut, the backdrop will be the spanking new Amazônia Arena in the northern Brazilian city of Manaus. The stadium, designed by Germany’s GMP, is certainly eye-catching - it is meant to look like a giant indigenous woven basket - but critics fear that the venue, which was finished over a year late and 30% over budget at a cost of £180m, could yet become a white elephant due to the lack of a strong football tradition in the city. Of equal concern in congested Manaus is the failure of local authorities to meet their promises on about £500m of related projects - an airport upgrade is still not finished and two major public transport schemes were scrapped. Manaus has declared holidays for public employees on match days in an effort to mitigate possible transport chaos during the event.

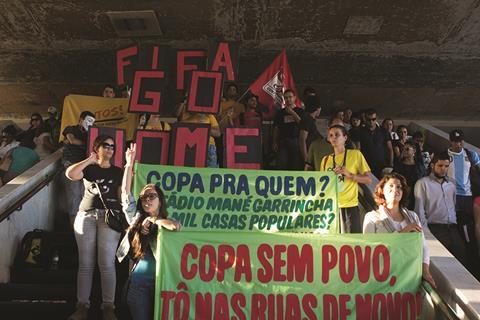

The city is not alone in its poor preparation - there have been delays or cost overruns in every one of the 12 host cities, fuelling public anger which led to widespread protests in Brazil last year. Recently former Brazilian footballer Ronaldo, also member of the World Cup’s Local Organising Committee, added his voice to a chorus of criticism, saying that he was “ashamed” of Brazil’s level of preparation. So what exactly has gone wrong?

Delays, debt and deaths

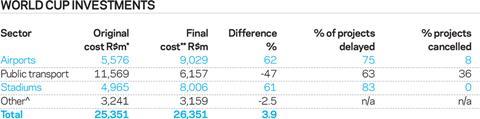

The 2014 World Cup has cost R$26.4bn (£7bn), based on data from the Financial Times’ Latin America research service, FT LatAm Confidential, which updates official data with information from project managers. Over 80% of this total has come from the public purse either by way of loans or direct investments, with the final cost coming in at R$1bn more than the original budget. It would have been a lot more were it not for the cancellation of a fifth of the public transport schemes.

Three-quarters of airport, public transport and stadium projects have been delivered late. Additional amounts have been spent by the private sector on 422 hotels, often using loans from public banks. But in some host cities, such as Cuiabá in the mid-west, demand surpasses supply and desperate authorities have called on local residents to offer up their beds to fans.

Of perhaps most immediate concern is the series of delays on the stadiums. Just two of the 12 venues were ready by the initial deadline of December 2012. A further four were complete in time for the Confederations Cup - the World Cup test run held in June 2013. The remaining six were delivered this year, two of them in April, just two months before kick-off. Although all of the stadiums have now been handed over to Fifa, the time available for carrying out essential tests and adjustments was much shorter than planned. Some facilities, such as television screens, were still missing from the press area during the final test at the Arena de São Paulo on 1 June and part of the roof in the western area of the stadium will only be installed after the World Cup as the glass used had to be changed (see box).

On the positive side, the consensus is that the stadiums have been built to a high standard and that none of the problems highlighted are likely to cause serious hitches during the matches themselves. But the delays did cause costs to rise. In many instances workers had to be employed on extra shifts and more expensive prefabricated materials were used than were originally planned. The final R$8bn (£2.1bn) stadium spend was about two-thirds higher than that initially budgeted. The greatest cost overrun was on the Maracanã stadium in Rio de Janeiro, which cost R$1.05bn, 75% morethan budgeted, in large part because of changes to the design. It would have been even higher were it not for intervention from federal auditors who argued that the budget “border[ed] on complete fiction”, triggering the removal of some items that were listed more than once. Elsewhere auditors found cases of overcharging.

More worrying is the relatively high number of fatalities during the stadium construction. A total of nine workers died across four stadiums and their associated developments, seven more than on the construction programme for the 2010 Cup in South Africa. Investigations into these deaths are ongoing, but initial forensic reports as well as information from interviewees suggest that seven involved accidents.

Two fatalities that received considerable media attention were those on 27 November 2013 at the Arena de São Paulo. The deaths happened after a crane that was lifting part of the roof collapsed. A spokesperson at the main contractor Odebrecht says that it was “the 38th time that this type of procedure had been carried out in Odebrecht’s works” and that “up until then no other serious accident had occurred.” Sintracon, the national construction workers’ union, has received reports from workers involving a total of 521 serious accidents nationwide during stadium construction. Antônio Ramalho, president of the São Paulo chapter, says some stadium workers were on 18-hour shifts and believes that this may have contributed to some instances of fatalities and accidents. “A lot of projects weren’t ready on time, this put pressure on workers,” he says.

Airports have also been beset by delays. Nine out of 12 projects will not be completed in time for the World Cup, although in many cases only relatively minor changes will be necessary afterwards. Total spend in this area increased by about 60% to R$9bn from the original budget, but much of that extra amount was the result of investments in three privately-run airports, two of which were finished on time.

In contrast public transport, initially billed as one of the major legacies of the event for ordinary Brazilians, has seen total investments cut by almost half to R$6.2bn. A total of 19 schemes were cancelled and 63% of the remainder will not be ready for the games. This poor performance helped ignite public opposition to the World Cup in mass protests last year - 1 million people took to the streets. It’s not hard to see why. Historical underinvestment and incentives towards car use have congested cities. Commutes in rickety buses of up to four hours are not uncommon, and users say they feel unsafe. São Paulo metropolitan region has the most extensive metro network in the country, but at 75km it is still 80% shorter than that of Greater London, despite São Paulo having three times the population.

Bad planning and bureaucracy

“There have been a series of errors,” Paulo Simão, chief executive of the Brazilian Chamber of the Construction Industry (CBIC), an industry lobby, tells Building. “It starts with bad planning and disorganisation and also involves delays in projects and tenders. All this led to major and lamentable delays.”

An example of this bad planning is on the two transport projects that were scheduled in Manaus. Federal auditors blocked funds after they found that the schemes followed part of the same route and even had some stations in the same location. Without sufficient resources of its own to pay for the work, the state government cancelled the schemes.

Deputy minister of sport Luis Fernandes admits that the federal government “should have had […] closer integration with the Local Organising Committees from the very beginning”. “We were only included […] a little more than two years ago,” he says.

There is also a sense among much of the public of pervasive corruption on some World Cup projects. While much of this is unsubstantiated, in 2011 the Court of Justice of the Federal District in the capital Brasília found the president of the state transport company, José Gaspar de Souza, complicit in fraud designed by two bidders, Dalcon and Altran, to share the works on the Brasília light rail scheme linking the airport with the city. As a result the R$364m project was shelved.

But perhaps the biggest problem has been Brazil’s famous bureaucracy. “There were a lot of delays in the definition of laws and rules, as well as in the release of funds,” says Simão. Despite efforts by the federal government to speed things up, the public tendering process in Brazil can be notoriously slow, as can the time spent on obtaining environmental licences. Legal disputes over land expropriations dragged on for over a year in some instances and the frequent interventions by the multiple and overlapping audit bodies also sometimes held things up.

It is no surprise then that Brazil’s own goal on World Cup preparation is raising questions over the same country’s preparedness - or lack of - for the Rio Olympics in 2016.

Olympics setbacks

In April vice-president of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) John Coates commented that the preparation for the R$37.5bn (£10bn) Rio 2016 Olympics was “the worst” he had “ever experienced”. Although he subsequently withdrew his comments, they fuelled widespread concerns about the city’s readiness, coming as the German sailing team also complained that the Guanabara Bay next to the city was too polluted for test events later this year. To make matters worse, the tendering of works for essential improvements to one of the four main sites, the Deodoro complex, is significantly behind schedule.

Deputy minister Fernandes argues that overall the preparations are “on time” and that the improvements to Deodoro “are all very simple projects.”

However, the delay on tendering works at Deodoro was because responsibility for the project kept getting shifted from one level of government to another. This suggests that in some instances at least the Olympics suffers from the same problems of bad planning and lack of co-ordination as the World Cup.

Some transport projects, such as a new metro line, are advancing and excavation works on the Olympic park (which also includes the athletes village) are complete, but not everybody is convinced. “At the beginning I was a major enthusiast about the 2016 Olympics,” says the CBIC’s Simão. “[But] I’m very worried. I hope Rio will learn from the mistakes of the World Cup and improve things.”

Arena de Sao Paulo

When the World Cup kicks off on 12 June at the Arena de São Paulo many of the 68,000 expected fans may not realise that just a fortnight before final tests were still being carried out at the venue for this momentous event.

The last-minute nature of these preparations follows a series of problems in the development of the city’s World Cup venue.

São Paulo authorities originally planned to use an existing stadium. But the R$555m project was rejected by Fifa in 2010 and the event was moved to the Itaquerão stadium, requiring a rebuild that added R$265m to costs. Further setbacks came when bank funds were delayed. Then in November 2013, just a month before the planned completion, a crane collapsed. The accident caused the death of two workers and damaged part of the facade, although not the terrace structure, according to contractor Odebrecht. Itaquerão was inaugurated in April 2014, but some of the facilities in the press area were still missing on the final test on 1 June and part of the roof structure will only be installed after the Cup.

Online football competition

Building is able offer a fantastic competition prize of two tickets to watch England vs Slovenia at Wembley as part of the European Championship Qualifiers on 15 November. All you have to do is predict which football teams in this year’s World Cup will battle through to be finalists on 13 July and ultimately who will be the victor of that final match. But hurry, we need all entries before the first match kicks off between Brazil and Croatia at 9pm, 12 June. Terms and conditions are online. To enter go to www.building.co.uk/worldcupcomp.

No comments yet