The first of Boris Johnson’s promised 40 hospitals will open this month. But huge delays to the £22bn programme mean that, months before an election, procurement for most of the work hasn’t even begun and there is no certainty that Labour will push ahead. Joey Gardiner asks what it all means for construction

April is shaping up to be an important month for the long-delayed – and much-derided – plan to build 40 new hospitals in the UK.

The £22bn New Hospital Programme (NHP) has been bogged down by bureaucratic inertia since former prime minister Boris Johnson first promised to build the facilities during the 2019 general election campaign. But, nearly five years later – and just months before Johnson’s successor Rishi Sunak faces his own electoral test – construction of the first of those hospitals is finally due to complete, with the opening of the £50m Dyson Cancer Centre alongside the Royal United Hospital in Bath.

Even more significantly, Building understands that industry figures have been invited by the team behind the NHP to attend briefings unveiling the long-awaited standardised hospital designs which the programme is supposed to roll out. Insiders expect procurement of a construction framework designed to deliver the buildings themselves to commence shortly after.

But despite this encouraging progress, huge questions remain over both the programme, and investment in the health estate more widely. Last year the National Audit Office found the NHP had been subject to substantial delays, had not offered value for money, will not complete 40 hospitals by 2030 and was subject to further serious risks of failure.

The Department for Health and Social Care has still not had its programme business case agreed by the Treasury, amid reports that officials have asked for £4bn more funding.

And, while the NHP makes slow progress, the wider health estate continues to deteriorate, with the cost of backlog maintenance – the work on repairing leaky roofs and broken lifts that should already have happened – having risen to £11.6bn, according to the NHS’s own assessment. Added to all these problems is the prospect of the political disruption likely to be caused by an election this autumn.

>> Also read: School buildings crisis: what can the next government do to save our schools and colleges?

>> Opinion: How much the next government spends on the NHS estate will be critical to its future

In the second of Building’s pre-election updates, we examine what this mixed picture means for the industry.

Bouyant

Inflation-adjusted public sector capital spending on healthcare has actually been modestly rising in the past few years, with £2.6bn spent in 2023. This was 6.6% up on 2022 and comes after spending dropped to an unprecedented low of less than £1.6bn during the pandemic.

The Construction Products Association expects spend to carry on rising by 2% a year this year and next, boosted by the letting of £450m of contracts for the NHP – albeit it said in its latest output forecast that actual construction progress on site had been “negligible” to date.

Some in the sector are clearly feeling the benefit. Rory Pollock, healthcare sector leader at contractor Laing O’Rourke, which last year won both the £700m Monklands hospital job in Airdrie and the £300m Cambridge Cancer Research Hospital – part of the NHP – while completing work on the first phase of the £700m 3Ts Trauma Centre for the Royal Sussex County Hospital in Brighton, says the market feels buoyant.

“We’re quite optimistic about the sector, and we are winning work,” he says. “The market in general is pretty buoyant.”

But if the sector is gearing up in preparation for the NHP, much of the increase in workload to date is down to other projects. Richard Mann, director at consultant Aecom, which has been appointed alongside O’Rourke on the Cambridge Cancer Research Hospital job, says his firm is also “very busy” delivering other NHS priorities, such as projects in the £1.5bn programme to build out 50 new surgical hubs and over 100 community diagnostic centres.

These are facilities designed to ease the NHS backlog in routine surgery and treatments. Much of the work is coming forward through the Procure 23 framework, the latest iteration of the longstanding NHS construction framework, set up to procure £9bn of work over four years.

Underinvestment

But, notwithstanding the recent rise in sector output, there is little doubt that the work being undertaken currently does not begin to touch the scale of the demand. The NHS estate, which has around 1,500 hospitals in England, has been suffering from severe underinvestment for at least a decade, during which period, according to the NAO, the cost of the maintenance backlog has more than doubled in real terms.

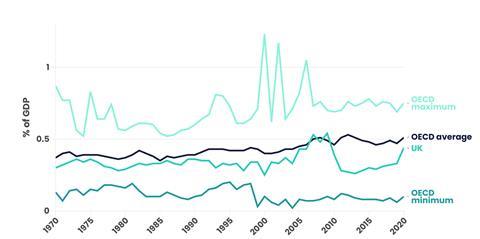

An analysis by the NHS Confederation, which represents NHS trusts, found that the UK has consistently spent less money on capital investment than its OECD peers for more than five decades – most starkly since the onset of Coalition-era spending austerity (see graphic below).

UK lagging behind on healthcare spending

Around 14% of the estate – 284 buildings – dates from before World War Two, and around half from before the 1980s. Into this situation has come the RAAC crisis, with 41 buildings across 23 trusts affected, including seven entire hospitals.

Given this deteriorating estate, last month saw a series of serious incidents with NHS facilities, such as the collapse of the ceiling of an intensive care ward on a patient on life support at the Princess Alexandra Hospital in Harlow, and a lift plummeting four floors at the Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel, an incident which broke the leg of a surgeon.

The NHS estate is in a desperate situation, with the health service crying out for capital funding to repair crumbling estates and invest in the latest technology

Rory Deighton, NHS Confederation

Dame Meg Hillier, chairwoman of the Commons public accounts committee, said the “chickens are coming home to roost” after years of underinvestment in NHS facilities. It is hardly surprising then that last year an Institute for Government report found that low capital spending was “seriously harming” NHS productivity, while the NHS Confederation makes the case that increased capital spending is the number one priority of NHS leaders.

But nothing extra was allocated in the recent spring Budget to new buildings, and Labour has made no specific promises on capital spend if it is elected.

Rory Deighton, director of the acute network at the NHS Confederation, says the NHS estate is in a “desperate situation”, with the body calculating the health service requires an extra £6.4bn per annum – more than tripling current spend – to “repair crumbling estates and invest in the latest technology”.

He adds: “If we are to make the productivity and efficiency improvements needed to tackle the waiting list backlogs, we need to address the NHS’s crumbling estates.”

Delays

Despite this level of demand, the promised programme of 40 hospitals has been very slow to get going. The NAO report said only three versus an expected five of the first cohort of hospitals had opened by June last year (see explainer box), and that the rest had been delayed by up to 16 months.

All of the schemes in the second cohort should have been under construction, but with delays getting the funding agreed with Treasury, and in developing the standardised designs for the programme – known as hospital 2.0 – no full building work had started by May last year. The Institute for Government report said the Treasury was “not keen” on Johnson’s manifesto proposal and had “done little to help it be realised”.

The department confirmed to Building that the Treasury has still not signed off the programme business case for the NHP, despite “indicative” investment of £18.5bn having been approved to cover 2025-30.

Aecom’s Mann says delays have been exacerbated by the RAAC crisis, which saw the department last year re-prioritise the whole programme to ensure the seven fully RAAC-built hospitals were included, given that only two of them had been originally part of the NHP.

“Of the original programme we would perhaps have seen some of those projects on site by now,” he says. “The re-prioritisation of the programme has slowed the programme down.”

Asked about the delays, a spokesperson for the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), said it had been “backed by over £20bn of investment”, which had given trusts “indicative allocations to work within and develop their plans further”.

The spokesperson added: “We continue to work closely with individual trusts in the programme to ensure each hospital is the right size to meet local needs and affordability, and we remain determined to make sure each new site meets the needs of the NHS now and in the future.”

Quiet

Mott Macdonald is the NHP’s interim delivery partner, with KPMG, alongside other consultants, appointed interim programme partner on the work, keeping many in the sector busy. But Mann concedes that many contractors, further along the project timeline, will have seen little evidence of the flow of work from the NHP thus far.

“If you are a contractor, I would say, yes, you’re seeing very little of the large projects [right now], but in the professional services group, we are working on schemes right now that are progressing through the three or four stages [to get projects on site].”

The projects are not coming through. It’s probably the quietest it has been for some time in terms of opportunities coming to market

Simon Kydd, Wates

Which perhaps explains why Simon Kydd, education and healthcare director at contractor Wates, does not see the market as quite so buoyant – the opposite, in fact. “The projects are not coming through. It’s probably the quietest it has been for some time in terms of opportunities coming to market,” he says.

Into this environment, sector professionals have been invited to a “technical briefing” by the NHP team this month on the new Hospital 2.0 concept, ahead of a full launch expected in May. Hospital 2.0 is meant to be the department’s grand vision for the NHP programme – securing efficiencies through standardised hospital design, procurement and off-site construction.

Originally supposed to be in place from the end of 2022, the NHP team believes that Hospital 2.0 can make projects 25% cheaper and 20% quicker to build. Andrew McNulty, head of healthcare at consultant Gleeds, says: “We’re all hotly anticipating the release of Hospital 2.0 (H20) at the end of May.”

Wates’ Kydd says a procurement of a framework designed to deliver Hospital 2.0 projects is anticipated to begin shortly afterwards. However, there is a growing consensus that the programme cannot afford to wait further for this standardised concept to be embedded in the major hospital projects on which design work is already well-advanced.

Contractors such as Kydd, and Laing O’Rourke’s Pollock, say they hope that well advanced schemes can be brought to market under existing frameworks such as Procure 23 without major redesigns, to avoid delay. A separate source close to the programme, says: “Hospital 2.0 is likely to be iterative. It will develop and ultimately it will be phased in over time.

“It is reasonable therefore to expect that some schemes will come forward in advance of the full capability of Hospital 2.0, albeit they will draw as much benefit as possible from it.”

Rory Pollock says: “I think they are looking at options to fast-track or accelerate certain schemes through existing frameworks which we’re certainly supportive of. There’s an opportunity to get the ball rolling and set up pathfinder hospitals, which we can all learn from.”

Imaginary hospitals

Tempering any optimism, of course, is the problem of the likely disruption caused by the forthcoming election, which Gleeds’ McNulty says is potentially already starting to weigh on procurement decisions, despite Pollock’s hopes that procurement can start pre-purdah.

McNulty says: “There is an anticipation the outcome of the election may have an impact on major programmes. I would expect there to be change. Any new government will want to review the content and value of its programmes.”

Labour, the current bookies’ favourite to win, has made “build[ing] an NHS fit for the future” one of its five core missions if elected. However, this does not appear to relate to physical construction.

>> Also read: Cost model: Evolving the design and build of community diagnostic centres

The party’s detailed mission briefing makes no specific pledges around capital spending on building hospitals, and if anything seems to imply that Labour might consider culling projects. While it says “we cannot go on with a crumbling NHS estate”, the document adds that “a responsible government does not promise an imaginary ‘40 new hospitals’ that they will never deliver”.

It then insists that Labour would make an “assessment of all NHS capital projects”, designed to prioritise and ensure value for money, “before we commit to any more money”.

All of which is concerning to Wates’ Kydd. He says: “Currently the biggest risk to the programme is a change in government. Obviously historically Labour have tended to spend more, but you look now and it’s not the messaging.

“[Hospital 2.0] procurement is due to start in Q2, and we want to commit a lot of resource to that. But [shadow health secretary] Wes Streeting hasn’t mentioned it at all.

“Clearly, we don’t ideally want to commit a lot of resource to something that gets significantly stalled in a lengthy review by a new government.”

Labour’s options to fund new capital projects would obviously be constrained by the fiscal situation they would inherit, if elected. Which leads McNulty to suggest that a review is needed of routes to bring private finance in to get projects off the ground.

In the two decades to 2018, PFI was used to finance the construction of 160 hospitals. Other methodologies were also utilised, such as NHS Lift public private partnerships, which funded 342 smaller schemes worth £2.5bn, and deals over NHS land, know as strategic estates partnerships.

“Sources of funding will need review,” McNulty says. “There’s always such a high demand, and a reliance on exchequer funding.

“Given the level of funding that is now required by the NHS, you have to ask, would it be right to look again at public private partnerships, NHS Lift, and strategic estates partnerships?”

The sector is likely to be hoping that these ideas form part of a future government’s review of capital projects after the election. Otherwise, it appears likely that public health estate construction will continue to fail to meet the clear demand to update the NHS’s dilapidated buildings.

New Hospital Programme explained

The programme consists of up to 48 schemes delivered in five separate waves, or “cohorts”. Eight of the schemes were already in progress prior to Boris Johnson’s 40-hospital promise, and therefore are not formally counted as contributing to the commitment.

With the last eight (unnamed) schemes not due to complete until after 2030, the National Audit Office estimates that the government will – at best – build only 32 hospital projects by 2030, with even that target at risk. The Treasury has committed £3.7bn to the programme up to 2024/25, with a further £18.5bn of “indicative” funding available to 2030 subject to programme business case approval. The Department of Health and Social Care had asked for up to £20-30bn.

Cohort 1 Eight projects, of which only one, the Dyson Cancer Centre in Bath, counts towards the NHP. Three have already opened and the Dyson Centre is due to open this month.

Cohort 2 Ten schemes, which includes one that does not count toward the NHP. Construction yet to start on any at the time of the NAO report.

Cohort 3 Eight schemes, mostly or entirely for construction from 2025-26 onwards.

Cohort 4 Fourteen further schemes for construction from 2025-26 onwards

Cohort 5 Eight further schemes not yet selected, which the NHP would construct in the late 2020s

Election focus

As thoughts turn towards the next general election, the UK is facing some serious problems.

Low growth, flatlining productivity, question marks over net zero funding and capability, skills shortages and a worsening housing crisis all amount to a daunting in-tray for the next government.

This year’s general election therefore has very high stakes for the built environment and the economy as a whole. For this reason, Building has launched its most in-depth election coverage yet, helping the industry to understand the issues in play and helping to amplify construction’s voice so that the government hears it loud and clear.

Building is investigating the funding gaps facing the next government’s public sector building programmes, looking at the policy options available to the political parties.

In the coming months our Building Talks podcast will focus on perhaps the hottest political topic: the housing crisis. The podcast will feature interviews with top industry names who side-step soundbites in favour of in-depth discussions.

As the main parties ramp up their policy announcements, we will keep you up to date with their latest pledges on our website through our “policy tracker”.

No comments yet