Councils are exploring ways to stop companies involved in blacklisting from winning work with them

Major contractors previously involved in blacklisting could be hit where it hurts by being barred from public sector work, a committee of MPs last week suggested.

The move from the Scottish Affairs Committee, which has been investigating blacklisting since last June and has so far trained its fire on the likes of Balfour Beatty, Skanska and Sir Robert McAlpine, was designed to ratchet up the pressure on major contractors proved to have engaged in the practice.

However, what is less known is that plans to withhold public sector work from these firms are far more advanced than one might imagine.

Where it’s legal to do so, we won’t work with the companies involved with blacklisting

Liverpool councillor Nick Small

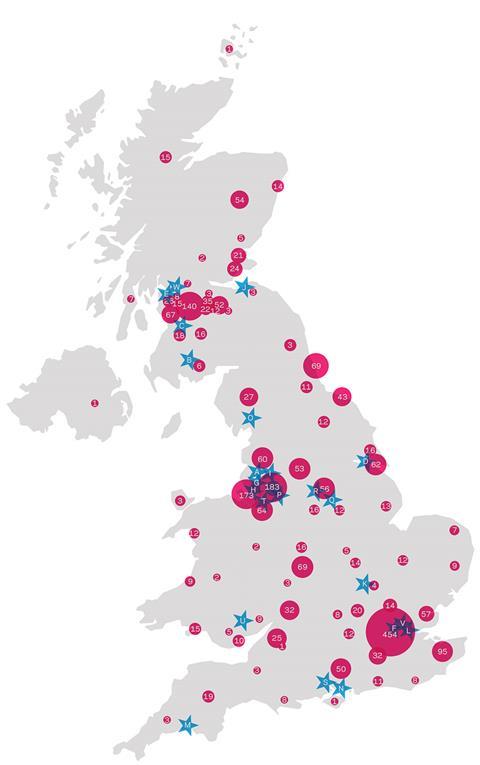

An investigation by Building has revealed that almost two dozen local authorities in the UK have already passed motions supporting a campaign by the GMB union requesting that they do not “award any more public work to the companies that operated the blacklist till they compensate those they damaged”.

The list of local authorities is by no means exhaustive, with the overall number set to grow in the coming weeks as other councils hold votes. It currently includes three London boroughs, five Scottish councils, and some very large players such as Liverpool council, which controls around £1bn of planned or current construction projects.

But why are local authorities trying to implement such a procurement policy and do they have the powers to do so?

Moreover, considering the £40bn pipeline of government-funded construction and infrastructure projects, what will the impact of such a radical measure be for the firms targeted?

Local councillors who spoke to Building were unapologetic about their stance, complaining that central government has dragged its feet despite indications that blacklisting is continuing.

Councillor Nick Small, Liverpool council’s cabinet member for employment, enterprise and skills, who also has a seat on the city mayor’s cabinet, says the authority was keen to highlight what it views as a “historic injustice”.

He says: “Liverpool has a very high number of construction workers who have been affected by this from the seventies and eighties onwards. Some have suffered financially and we want the government to do more about this.

“Some sort of system of compensation needs to be set up and we’ve said where it’s legal to do so, we won’t work with the companies involved with blacklisting.”

Small believes this stance is already having some impact, with contractors writing to the council to detail how they have reformed their practices.

Crucially, it appears councils are legally within their rights as clients to take this action, although that is not to say they could not be challenged.

Lawyer Rupert Choat, head of construction disputes at CMS Cameron McKenna, points to the Public Contracts Regulations 2006 which state that a contracting authority can treat a contractor as ineligible for work if they have “committed an act of grave misconduct in the course of his business or profession”.

“By definition this regulation is designed to get at things which happened in the past and it clearly gives authorities the discretion to act when a contractor has been guilty of ‘grave misconduct’,” Choat explains. “If any of the local authorities act on [these motions], it has the opportunity and threat of setting a bit of a precedent.”

Councils could potentially bring in a formal policy effectively “blacklisting” particular contractors. Alternatively, they could question them about their record on blacklisting through the pre-qualification questionnaire and score them accordingly.

However, Choat cautions that both types of action are not without risks for the public sector client. Contractors could challenge councils that the practice of blacklisting does not constitute “grave misconduct” or that it was carried out by rogue employees.

For the 44 firms originally found to have paid The Consulting Association to access its blacklist database, the prospect of councils stealing a march on central government to punish them may be of serious concern.

Kevin Cammack, an analyst at Cenkos Securities, who follows the contractor most targeted by the GMB - Carillion - says all the firms involved face the prospect of having to weigh up the financial costs of paying compensation with the costs of losing out on valuable public work.

“Nobody wants to be regarded as off the tender list of significant local authorities around the country,” he says. “If there are a significant number of big local authorities doing this, there is no doubt in my mind that these companies will seek to find a resolution to this - even if it costs them money.”

A spokesperson for the UK Contractors Group describes the councils’ actions as “inappropriate”, adding: “These issues are historic and blacklisting has no place in today’s industry.”

The CBI Construction Council, meanwhile, insists it is “down to the courts” to establish whether and how blacklisting occurred, saying the practice is “illegal and totally unacceptable”.

And one contractor involved, Carillion, suggests that dialogue rather than punitive measures should be pursued.

“We recognise that the industry faces a challenge to rebuild trust with some of our key partners, but we believe that the answer lies in constructive dialogue rather than more legislation or regulation,” a Carillion spokesperson says.

For firms already facing the ire of MPs and the prospect of being caught up in compensation claims lodged in the High Court, the moves by local government are just another example of the pressure mounting as the blacklisting saga continues to gather steam.

BLACKLISTING – THE NATIONAL PICTURE

A Bolton

B Dumfries and Galloway

C East Ayshire

D Hull

E Inverclyde

F Islington

G Knowsley

H Liverpool

I Manchester (Green Deal only)

J Midlothian

K Milton Keynes

L Newham

M Plymouth

N Portsmouth

O Preston

P Rochdale

Q Rother

R Sheffield

S Southampton

T St Helens

U Torfaen

V Tower Hamlets

W West Dunbartonshire

No comments yet