This year marks the peak of the retail cycle. With the economy slowing, can future schemes deliver quality and innovation? Simon Rawlinson and Richard Taylor of Davis Langdon investigate

01 / introduction

In 2008, nearly 5 million ft2 of space in large retail developments will open in the UK, in projects ranging from mixed-use schemes in Bristol and Liverpool to enclosed malls such as London’s White City. These openings mark the high point of the retail development cycle.

However, as the impact of the credit crunch has widened, prospects for rental growth and increasing capital values have declined. As a result, the next generation of centres could be developed to very different value criteria, involving the review of many aspects of investment including public realm, logistics, sustainability and links to public transport.

The revival of retail development has also coincided with the work of the Urban Task Group and Cabe, which have championed the cause of mixed-use urban regeneration. Although the overall aim of retail development remains focused on generating pedestrian flow and providing the right retail mix to create critical mass – the wider development challenge has become significantly more complex, involving the reintroduction of town-centre housing, the creation of a vibrant, mixed-use economy and the enhancement of the sense of place and connectivity within the town centre.

One consequence has been the emergence of alternative models of retail development, characterised on the one hand by enclosed malls, and on the other by the development of more traditional streetscapes with a mix of covered and open space.

Although enclosed malls have many advantages with regard to the creation of a high-quality retail environment, they can be difficult to integrate into an existing town centre. By contrast, the absence of weather protection found in open schemes is seen as a disadvantage by some development partners.

02 / town centre retail

The current retail development cycle has been focused on town centres, largely as a result of planning guidance that has pushed development in that direction.

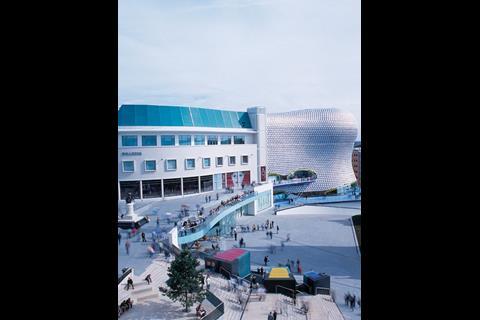

The first landmark urban scheme was the redevelopment of Birmingham’s Bullring, completed in 2003. The fact that it has taken more than 10 years for other projects to be built shows how complex and time consuming land assembly, design and construction issues can be. In-town retail schemes take many of the positive aspects of out-of-town development – large unit size, convenience, development quality and some degree of shelter, and combine the variety and interest of a town centre location with the wider benefits of a mixed development. For all the headaches associated with estate management, residential investment and so on, town centre schemes benefit the wider public and offer investors a diversified source of income. In the long run, these locations are expected to be the sustainable development option as far as environmental, economic and social dimensions are concerned.

Large-scale in-town developments offer a huge masterplanning and urban design opportunity and it is not surprising that designers have responded positively to the challenge of reviving the vigour of town centres. The commitment of developers in taking forward these complex schemes has also been huge, particularly as it has involved moving into unfamiliar areas of development such as residential, hotels and leisure facilities, together with a more extensive site assembly and consultation processes. In shifting their focus in-town, developers and investors have recognised that town centres have the scale and “competitive identity” to draw high footfalls based on their large catchment areas. They can also support a varied retail and leisure offer, which is necessary to motivate consumers to visit more often and to stay for longer. This, in turn, gives shops the potential to extend their trading hours. Furthermore, with good public transport links, town centres are well placed to benefit from the effect that the increased cost of fuel is having on car travel.

The key differences of town-centre schemes compared with a traditional out-of-town mall are as follows:

- Planning can be based on city blocks rather than the arrangement of retail units along an arcade. The same retail design principles of clear sight lines, the use of anchors to direct footfall and the maximisation of retail frontage remain, but other urban design approaches can be adopted to achieve them. These include the use of established street networks or an emphasis on sight lines, vistas or existing historic features

- Greater attention is focused on designing schemes that relate to their surroundings. For example, the need to ensure the “permeability” of both malls and open schemes means that the existing street layout is respected, and accessibility and footfall are enhanced by pedestrian through-traffic

- Architectural design can be more varied, particularly in open-street schemes, where individual buildings will be designed to relate to or contrast with one another and to the spaces between them. For example, 25 practices have been employed in the design of of Grosvenor’s Liverpool One. Alternatively, mall-based schemes such as those in Birmingham and Leicester have iconic anchor store designs to create an identity.

- Extended trading hours, particularly for open-street schemes, which cannot be locked up at night. Longer opening hours benefit the night-time economy, but developers have to consider how spaces might be used, and what security, cleaning and maintenance regimes need to be put in place to ensure the continuing attraction of the centre.

- Parking, logistics and servicing – space constraints mean that urban schemes usually need multistorey or basement parking and will also rely on basement servicing to most units. Underground servicing represents a significant investment but in open schemes keeps vehicles off pedestrian streets and also supports scheme-wide services distribution related to combined heat and power plants and IT backbones. As developments’ values have fallen, underground servicing is seen as an area for rationalisation in value engineering studies, a possible alternative being the through-mall servicing commonly used in the Middle East.

03 / Cost drivers for town-centre retail

Although many town-centre schemes do not have an air-conditioned mall, in-town retail is typically a more complex and costly development proposition.

Key cost drivers include:

- Brownfield sites

In addition to land assembly, demolition and decontamination costs, town-centre schemes may be required to retain and refurbish existing buildings.

Other issues associated with previously used sites include services diversions

- Design quality

Working within town centres sets a context and quality benchmark. As a result, potential savings on a mall, including a roof and air-conditioning, are likely to be offset in part by the additional costs associated with multistorey construction, the quality of facades and public realm. For open schemes developed to match an existing street pattern, wall to floor ratios may be higher. Other design cost drivers relate to planning and the preference for a consistent palette of materials across mixed-use buildings, which may require the use of higher grade materials for some uses than can strictly be supported by their development values

- Town centre construction

The logistics of working in tight town-centre sites without affecting existing traders inevitably makes programming and sequencing of operations more complex. Programmes are typically longer, driven by phasing and can also be affected by noise limits, restrictions on deliveries and so on

- Mixed use

Mixed-use development has been a key feature of most in-town schemes – bringing together retail, leisure and residential.

As part of a mixed-use solution, developers are commonly expected to provide community facilities such as libraries as part of their section 106 contributions. In the commercial elements, multistorey construction adds to cost and there can be compatibility and flexibility issues between retail and residential related to structural grids, the impact of ground-floor access on retail frontage and the arrangement of services distribution relating to both uses. Mixed-use buildings may also be difficult to adapt or redevelop in the future. owing to different lease structures.

- Development density

Common facilities such as parking, transport interchanges and goods yards have to be developed to greater density in town-centre schemes where land is more valuable and where the site footprint is more restricted. Underground servicing and car parking are less efficient from a space-use perspective than above-ground, are more expensive and will extend the construction programme.

- Public realm

Investment in a high quality public realm is a key part of the long-term success of an in-town scheme, creating distinct urban spaces and enhancing the quality of a visitor’s experience. All shopping destinations have upped their game with regards to the quality of finishes and furniture, fixtures and equipment. In particular, products used in open malls need to be more robust to withstand the elements and general wear and tear in a 24-hour environment.

04 / shopping centres and the value challenge

The UK has about 530 million ft2 of retail – 150 million of which is located in shopping centres. There is further potential for growth, as the UK has only half the retail space per capita that the US does. Department stores in particular have confirmed plans to roll out large store formats to a wider range of locations, but currently many retail schemes are being re-evaluated while they await funding and an improvement in prospects to ensure their viability.

Retail led the UK economy out of the nineties recession, partly on the basis of retail parks and large regional shopping centres developed with consents granted before planning policy shifted in favour of town centres. The rise of retail-led regeneration coincided with a period of rental growth, “yield compression” and increased demand for in-town residential which resulted in an increase in development values.

This justified the additional complexity, time and cost of in-town schemes. Although capital values remain at low levels, schemes are being thoroughly reviewed to ensure that they deliver best value. When retail development resumes in town centres, in 18 months at the earliest, developers’ commitment to investment in the urban renaissance will undoubtedly remain. However, the challenges may be even greater than before – sustainability requirements are becoming more demanding, regeneration challenges may be even tougher and residential schemes are unlikely to secure the values achieved during the buy-to-let boom. As a result, the resources to drive regeneration are likely to be somewhat constrained.

05 / the changing face of retail

Retailers are in a constant state of reinvention, and are continually changing their formats and ranges to increase their market share or to respond to changing customer expectations. Retailers can change their offer at a far faster rate than they can the buildings they occupy, so flexibility in unit design and leasing arrangements are important to ensure that successful retailers are not held back. An emerging trend in the UK, following common practice in Europe and the Gulf, is the anchoring of large schemes by food retailers, which have very different specification requirements.

Research by the British Council for Shopping Centres has identified four drivers affecting the motivations of consumers:

- The search for new convenience Requiring different retail offers to meet different needs, better integration with transport and parking and greater connectivity with the wider town centre

- The search for difference Placing greater emphasis on the breadth of the retail offer and the distinctiveness of the shopping experience

- The search for new responsibility Customers respond warmly to sustainability initiatives

- The search for wellbeing Retailers have to respond to a wider lifestyle agenda.

These factors have led to a change in retail practice and consequently on shopping centre design. These include:

- Fragmentation of the customer base

Retailers’ careful targeting of specific groups such as impulse buyers or the newly empowered “silver shopper” creates a challenge for developers who aim to create retail environments that are complementary to the values of their target shoppers. Parents with young families value security and convenience and younger shoppers enjoy the buzz of a dynamic, high fashion environment. In-town development based on city blocks and retained street patterns allows more opportunities to create “retail quarters” than a typical shopping centre arranged along a linear mall, and enables the clustering of complementary shops. Distinctions between quarters can be reflected in the scale of the blocks and streets, the retail mix and leisure offer, and also in street furniture and signage;

- The drive for size

Parallel to the fragmentation of the customer base, many retailers have sought to extend their product ranges to create the “destination pull” that occurs when a shop has a sufficiently wide and convincing offer to act as a draw in its own right. Many retailers – particularly in the value segment – occupy stores that are two to three times larger than they would have been taken in the nineties. With clear floor-to-floor heights in excess of 5m, this means that buildings focused on retail uses require large footprints, which can be difficult to reconcile with the street layouts that many town-centre schemes seek to reinstate

- Rise of the speciality store

In response to the drive for difference, developers also aim to create a competitive edge through the presence of speciality stores and independent retailers. These complement the mixed-used character of many schemes and need to be actively supported through the provision of appropriately sized and located units and flexible lease structures

- Retail as leisure

Large retail schemes can offer a diversified leisure destination and look set to benefit from the continuing blurring of shopping, leisure and entertainment. Retail destinations are increasingly used as a “third place”, that is, neither home or work, and they provide the setting for an affluent target market with a thirst for leisure and innovation. As a result, the proportion of space given over to leisure uses has increased and its prominence has grown – partly in order to encourage the development of the night-time economy

- The sustainability agenda

A combination of regulation, customer expectation and development partner objectives has been driving developers towards the goal of low-carbon retail development. Town-centre schemes obviously help in this regard and other initiatives have included the adoption of natural ventilation techniques, use of central CHP and initiatives to reduce power loads within retail units.

Although many of these initiatives align with the emerging trends of in-town retail, existing out-of-town schemes are also responding by refurbishing public areas, creating specialist malls and expanding their non-retail offer. Irrespective of location, the customer will be the beneficiary of continuing investment in the experience of the shopping trip.

06 / design management and procurement

In addition to the sheer scale of retail-led regeneration, there are a number of challenges associated with the delivery of large, mixed-use, town-centre schemes that have required innovative responses in the management of their delivery. The major challenges have been:

- Realisation of a diverse urban design solution

The masterplan is the foundation of a successful development, but many schemes involve a wide range of designers in the delivery of individual buildings. Although this approach should generate high quality designs, management is more complex and there is a risk of losing some benefits of design co-ordination and rationalised procurement. Delivering production information via large executive design teams helps to drive this consistency, but may result in some loss of design intent. Investing early in standard scheme-wide specifications and information exchange standards can help to reduce the loss of efficiency associated with the use of multiple teams

- Design management

This is a crucial discipline – not only to make sure that the programme is met, but also that production information is fully co-ordinated and ready for construction. Working with an extended design team also increases the number of interfaces, contracts and programmes which need to be managed by the client

- Logistics

Even though inner-town retail projects can be created in complex sites, they must be delivered under the same pressures as an out-of-town centre. Phasing the work to enable early trading by key retailers may be complex, with later phases being delivered in a trading environment. There has been a greater use of modern methods of construction recently, including prefabricated wall panels and service pods aimed at reducing programme durations, on-site labour and vehicle movement

- Main contractor procurement

The importance of risk management, the certainty of delivery and the involvement of banks in the choice of procurement strategy has resulted in the adoption of approaches that focus responsibility for design management, project delivery and commercial risk on the contractor. Two-stage design and build has been the commonest approach, with executive design team roles novated to the contractor.

The main contractor then has the option to appoint tier-two contractors on a site-wide basis for packages such as groundworks and some aspects of M&E, and to appoint some specialists to deliver elements of single buildings, such as the external wall package. The advantages of the two-stage, single contractor route include programme compression, single-point responsibility, central co-ordination of design and construction and volume purchasing. The downside, particularly in a hot market, is the restricted availability of contractors with experienced teams and limitations on the developer’s ability to exert commercial pressure during the second stage tender.

To secure more competitive bids, future schemes may be let on the basis of a single-stage tender or, for well-resourced and experienced developers, construction management could be used.

07 / cost breakdown

The cost model compares the construction costs of two options for an arcade serving a large town-centre shopping development:

- Enclosed comfort-cooled and ventilated mall

- Open arcade with canopies

The dimensions and overall design concept for the two options is kept constant, so that the costs are directly comparable.

The cost model focuses on the costs of the arcade only. Costs of retail shells, public toilets, the management suite, landlord’s areas and service yards are excluded. No allowance is included for a food court. The costs reflect a high level of specification, appropriate for a prestige, town-centre scheme.

The two-storey mall has a gross floor area of 7,000m2. It forms part of an overall shopping centre development with a gross floor area of 80,000m2, anchored by two large department stores of sized about 20,000m2 each.

Costs are current in October 2008, based on a location in the south-east of England. Costs of external works and services, design fees, statutory fees and VAT are excluded. The level of pricing assumes a two-stage competitive tender, for a design-and-build contract. Costs are based on a single-phase programme.

Adjustments should be made to the costs to account for variations in phasing, specification, site conditions, procurement route, programme and market conditions.

Downloads

Cost model - Retail development (PDF)

Other, Size 0 kb

Postscript

Davis Langdon would like to thank Mike Nisbet of Grosvenor and Chris Du Toit, Anthony Flynn, Marco Ielpi and Cris Bernardo of Davis Langdon’s retail development team for their assistance in the preparation of this article.

No comments yet