The demand for high quality healthcare facilities aiming to improve the quality of life of patients with serious illnesses is increasing. As well as meeting the requirements for providing medical care, these buildings must also offer a homely and therapeutic environment. Mark Robinson of Aecom reports

01 / Introduction

The UK population is living longer. The Office for National Statistics confirmed that “from mid-2005 the population of those aged 65 and over has increased by 21% and for those aged 85 and over by 31%”. Almost 20% of the population is now aged 65 and over, placing huge pressure on health and social care services.

Extended life expectancy is known to be associated with:

- Better informed choices through information and education for an improved health and wellbeing lifestyle – proactive health – affecting living conditions, hygiene, variety and balance of nutrition and exercise

- Availability of public high-end treatment services, continuing to increase with the likes of Guy’s new Cancer Centre and Christie’s and University College London Hospital’s upcoming proton beam therapy facilities

- Medical and technological healthcare improvements.

The period people live with long-term illness, including more complex illnesses, has increased and this trend is expected to continue.

Greater life expectancy across a generation of patients who expect high standards of care and choice will further drive the improvement of healthcare building design standards.

The NHS is focusing on healthcare closer to home, endeavouring to reduce demand on hospital services.

Facilities in which palliative services are delivered will need to adapt to cover both increased demand and a widening range of patient needs.

02 / Purpose

Palliative care covers health and social services for patients, and their families, of all ages and over the period of serious illness, an illness which is incurable, recurring, life-limiting or life-threatening. This form of care, to treat and manage patients’ pain, offers those who are suffering an opportunity to improve their quality of life. It is seen as a holistic approach since the care covers social services, such as psychological, physical and complementary therapy and spiritual support. Any palliative care provided within the last 12 months of life is generally regarded as “end-of-life care”. Palliative care, defined by many organisations, includes:

- Relief from discomfort and distress

- Rehabilitation

- Acknowledging dying is part of the process of living

- Maintaining life, not overly prolonging it

- Holistic approach to patient care

- For patients to live an active a life as possible

- Acknowledging a patient’s family or carer as part of the care offering

- Ultimately enhancing the quality of life.

The range of health professionals delivering palliative services is wide, including GPs, community nurses, occupational therapists, counsellors, physiotherapists and specialist consultants. Therefore these services take place in numerous building types, including community health centres, hospitals, care homes, hospices and homes of residence.

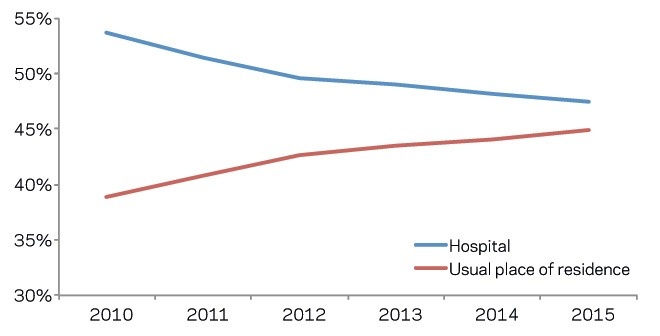

The Office for National Statistics released “Place of Death Trend Statistics” for England up to 1Q 2016. The data illustrates an upward trend with the choice of end-of-life care being the “usual place of residence”. This aligns with data collected from an earlier report in 2008 that confirmed the preference was to die at home. At the current time, those that die in a hospital are close to 50% with “up to 74% of people preferring to die at home”.

Percentage of deaths: Place of occurrence

More recently, Hospice UK has released research confirming that “less than a fifth of hospice care for adults was delivered within inpatient units”. The “majority of clinical care for adults is delivered in different community-based settings including: people’s homes, day hospice and hospice outpatient services”.

With increasing expectations for a community-based care setting for end-of-life care, alongside the known pressures on hospital services with the increased population, palliative services must be appropriately prepared and supported to deliver the quality of care required. This means not being solely focused on inpatient services and ensuring no separation of the NHS and hospice charity sector.

A close relationship between the NHS and hospices delivering end-of-life care will benefit all. Expansion of joined-up provision, through education and training centres and an increased drive for further integrated outreach services within the community health setting will benefit all (a “hub and spoke” model).

A good example is at St Christopher’s Hospice, which is seeking to build a world-class centre of learning in London for healthcare professionals working in palliative care, designed to accommodate “more classes to train many more groups of students, and provide vital new facilities such as a skills lab for practical, hands-on learning, and improved e-learning facilities”. It is a building necessary to “ensure the availability and quality of end-of-life care continues to improve in the UK and around the world.

03 / Funding

From 2015 to 2016, hospices provided patients and their families with end of life service care to approximately 200,000 people, which equates to just over 30% of all UK deaths. Approximately a third of hospice funding is provided by the NHS. This is mostly in the form of a block grant from local commissioners, but is likely to move towards a tariff (per patient or care session) based system. Over the last few years NHS funding for hospices has largely remained static or even been reduced for many hospices.

Hospices are charities and typically provide all their care free of charge, needing to raise the bulk of their funding from the local community. Funding is often via charity shops, local fundraising, lotteries and charitable grant funding, which tends to be restricted to specific projects.

Hospices need to have a diverse portfolio of fundraising programmes encompassing events, businesses, legacies, direct marketing appeals, collections and fundraising from families of patients, local people and groups (such as schools and churches). The main way hospices have been able to grow income has been via applying for specific grants either from the government or charitable trusts and foundations, mostly for capital builds or refurbishment.

Hospices have used these capital grant funds as opportunities to improve patient facilities – ensuring inpatient centres are up to modern standards or by developing modern outpatient facilities. These meet the trends of the new generation of patients – those who prefer to be cared for and to live in their own homes for as long as possible. However, capital grants do not provide revenue funding to cover costs of care – mainly nursing care. This means that hospices need to work even harder to generate unrestricted income to pay for salaries of clinical and care staff, which is by far the main cost for most hospices.

04 / Design principles

Whatever the end market sector, the majority of new or refurbished buildings will seek to provide a space which is considered safe, effective and efficient. The planning of public health buildings is unique and complex for a number of reasons and goes beyond this to include:

- Facilities for treatment of disease but also the prevention of disease

- A space which is not just uplifting but which promotes wellbeing and aids healing

- A space, which is, in many cases, filled with numerous services over a number of floors but must feel of human scale

- Flexibility, adaptability and foresight to reflect the fast-paced technological era without over provision or redundancy

- A building that meets patient and family demands where service expectation is increasing

- To deliver all the above under a restricted capital and life-cycle setting.

Evidence-based design (EBD), which is proven scientific research over a number of decades, supports architects, designers and clinicians as first principles in shaping healthcare buildings.

With end-of-life care there is known to be a heightened awareness from patient, families and carers of the building’s environment. With the focus of palliative care to comfort rather than cure, emphasis on the creation of a therapeutic space is critical.

Accommodation schedules typically include:

- Front of house Reception, cafe, visitor toilets

- Treatment Consultancy rooms, rehabilitation areas, inpatient accommodation (wards / bedrooms) education space, meeting rooms, patient social space, family and carer social spaces, mortuary, bereavement space and multi-faith rooms

- Back of house Kitchen, administration offices, meeting rooms, plant room.

Outside space

The importance of natural light cannot be overestimated. Ward and bedroom space must ensure window views to the outside from a minimum bed height level or preferable to the floor. Widening bed / ward circulation space and adding access doors allow an ease for external bed access. Multiple-storey, larger balconies suitable for beds should at least be considered along with associated structural requirements.

Specification

Although a homely setting, the material and configuration of accommodation is still required to meet the standards of the associated commissioning body, such as the Care Quality Commission. Integration of EBD into the building (daylight, natural ventilation, views to the outside, way finding, quietness, social support, distraction, freedom of movement, art and music) will de-stress the experience of being in a clinical environment.

Control

Accommodation areas should provide for patient and family control over the environment. Accordingly, the ability to control temperature, lighting, curtains, entertainment systems, internet access, nurse call and video calling service should be within reach at all times and with ease of use.

Privacy and dignity

The design needs to strike the right balance between nursing observation of patients and the patient’s own privacy. Furthermore, consideration must be given to allow patient families and carers to have their own space outside of the patient’s bedroom or ward, whether this is for contemplation or a need for private consultation.

Layout

The building should be designed with the patient’s, the patient’s family and the carer’s journey in mind. Appropriate health planning will ensure the best location of rooms such as mortuary viewing areas – allowing adjacent spaces for engagement and privacy. Design should ensure family and carer support continues to be available – accommodation such as bereavement space, multi-faith rooms, consultation rooms, gardens, and so on – without returning through wards or bedrooms.

Distraction

Palliative patients, and family, will experience a range of emotions associated with their illness: at times shock, stress, insecurity, frustration, anxiety, discomfort, fear and depression. The design response can support the reduction of these feelings. Art – whether integrated within the build, loaned or directly commissioned – can support a wider design strategy.

05 / Form

Various structural solutions are available for new or extended palliative buildings. These are decided through consideration of the site constraints, size, futureproofing and health planning layout. Where the space is available and the development is small in scale with reasonably good site conditions, load bearing masonry walls and strip footings will provide a cost-efficient solution with short construction lead-in times.

However, this solution may complicate any future internal adaptation and alterations in comparison with a framed and pad foundation option. A timber frame, or lightweight steel modular construction, increases flexibility and provides lightweight solutions, which are quick to erect. A structural steel frame offers optimum spans and a reasonably unrestricted form.

Given the importance of outside space, many facilities are single-storey providing a level surface for external access. However, this should not stop alternative solutions to provide the schedule of accommodation over multiple floors on restricted sites.

Royal Trinity Hospice in London undertook an extension and redevelopment of its grade II-listed building to provide modern inpatient facilities over two floors with the use of balconies and a stepped landscape garden.

06 / Services

The building services in an in-patient palliative care environment will reflect those typically found in a general healthcare facility. However, a key difference is the overarching principle that the building should have a homely rather than a clinical feel, which will affect the services design and aesthetic in a number of areas.

In reflecting a less institutionalised setting, sanitary ware should be equipped with traditional fittings and flush handles to encourage recognition. Accessibility, ease of use and wheelchair / bed height fittings must apply to all patient-controlled service points, power, lighting and the like. Any facility that provides care over more than one level will require a passenger and bed / evacuation lift.

The in-patient nature of the building will require extensive disposal and hot and cold water distribution to serve bathrooms and communal areas, together with kitchens, activity and treatment areas.

Wherever possible, the design intent should be a naturally ventilated building. This may take the form of openable windows / vents or ducted cross ventilation depending on the depth of floor plate. This negates the requirement for the multiple mechanical systems that may otherwise be necessary due to the differing functional requirements of the building. To heat the building, traditional LTHW (low temperature hot water) underfloor / radiator heating may be provided with mechanical background ventilation incorporating heat recovery for use during the winter. For localised areas of high heat gain that require cooling, individual refrigerant-based systems are likely to be appropriate. Dedicated mechanical extract ventilation is often required to serve kitchens, WCs / bathrooms and dirty utility areas.

Another key design factor is for the building to be situated and configured to maximise natural daylight. Electrical lighting in both communal and accommodation areas should reflect a domestic setting incorporating pendants and downlights as appropriate rather than commercial type fittings. A combination of colour hues and lux levels as appropriate for the functional areas will assist comfort levels. Operational considerations such as the impact of corridor sensor lighting on adjacent bedrooms are key.

Fire detection and alarm systems need to acknowledge patient requirements and limitations by incorporating silent / phased levels of alarm.

Medical gases and vacuum systems are provided via a central distribution system to accommodation and treatment areas with delivery via wall outlets or bed head trunking.

An overriding building management system allows monitoring and control of mechanical and electrical systems to ensure the level of environmental control is managed appropriately.

07 / Sustainability

New build hospices can be assessed under the sustainability assessment method BREEAM. BREEAM primarily evaluates a development against environmental performance benchmarks though it does have a section on health and wellbeing which covers issues such as daylight levels, overheating, air quality and acoustics, which are all typically beneficial for users of hospice care.

BREEAM is split into nine categories, each of which is divided into a differing number of issues. A set number of credits can be achieved for meeting the given standards. Each credit achieved contributes to the overall score, which links to an overall rating (for instance, a score of 70% achieves an “Excellent” rating).

BREEAM offers the flexibility to choose which credits to target to achieve the desired rating, though this is notably lessened where higher ratings are aimed for.

However, this means that tenants should not assume that just because a building has a BREEAM rating it has achieved a specific standard which they desire (for example, daylight levels).

Therefore, where hospice care providers are looking to lease a building with a BREEAM rating it is beneficial to request a breakdown of the credits achieved to ensure that the building offers an optimal environment in which to provide the type of care required.

For developer-occupiers of hospice care buildings it is essential that a qualified BREEAM assessor is appointed early in the design stage to aid the identification of those standards that can make a significant improvement to the quality of care provided. Issues such as natural daylight and ventilation, overheating etc need to be addressed from the outset and if overlooked will often be difficult and costly to retrofit into fixed designs.

It is also advised that, rather than setting an arbitrary target BREEAM rating, a more holistic approach is taken to identify and target the individual credits that offer the most significant benefits within the context of the hospice care proposed and any project constraints.

BREEAM covers a wide range of sustainable issues and therefore attaining higher ratings on projects with limited resources can result in having to achieve many low-cost, low-benefit credits in place of a single high-cost but high-benefit credit.

08 / Lifecycle

With ongoing pressures on budgets, operational costs continue to be scrutinised across all healthcare facilities. Operators therefore continue to make difficult decisions on where to expend their available budgets.

In respect of considering lifecycle expenditure, the decision of where to target expenditure is predominately focused around ensuring the ability to continue delivering core medical services and then patient care. In the palliative care sector these same drivers exist, but there is typically a heavier focus on the patient experience.

This difference in focus means that more organisations operating in the palliative care sector are now considering the benefit of increased lifecycle expenditure in areas which may have historically been considered more cosmetic, rather than the traditional bricks and mortar and M&E services of the buildings. Consequently the environment in which the patient is being treated is now designed to be less “sterile” with more of a social / home ambiance.

Rising utility costs also mean the need to consider more energy-efficient systems, such as different types of lighting systems and different approaches to heat and power for the facilities, including combined heat and power systems and photovoltaics. This is leading to a number of organisations undertaking whole life cost analysis of systems and products to make business cases for “spend to save” initiatives, which offset the initial capital costs through reduced operational costs.

09 / Cost model: palliative care

The cost model is for a three storey extension to an existing palliative care unit, creating inpatient and office accommodation with associated ancillary support services; both internal and external finishes to a good quality.

The building contains 1,444m2 gross floor area and is located in Greater London. Costs included are based upon 4Q 2016 and include for Group 1 and fitting of Group 2, but exclude external works, professional fees, surveys, VAT. The rates may need to be adjusted to account for specification, site conditions, procurement route and programme.

| Cost | £/m2 | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substructure | 267,450 | 185.21 | 8.4 |

| Allowance for site clearance, excavation into gradient site & disposal, 1 item @ £80,000 | |||

| Excavate and dispose of slab and foundations, 1 item @ £30,000 | |||

| 450mm wide x 500mm deep strip foundation with 140mm load bearing blockwork to DPC, 25m3 @ £250 | |||

| 650mm wide x 500mm deep strip foundation with 140mm load bearing blockwork inner skin and 103mm facing brickwork to DPC, 40m3 @ £250 | |||

| 175mm thick reinforced concrete ground bearing slab with two layers of A142 mesh, 630m2 @ £100 | |||

| Concrete lift pit and walls; excavate and disposal, 1 item @ £8,000 | |||

| 500mm thick reinforced slab to underside of PCC retaining wall, 87m2 @ £200 | |||

| Allowance for 75mm structural screed to ground floor slab, 630m2 @ £30 | |||

| Installation of new drainage system, including connection and integration within new substructure works, 630m2 @ £30 | |||

| Waterproofing details, 1 item @ £15,000 | |||

| Frame & upper floors | 199,500 | 138.16 | 6.26 |

| Allowance for lower ground floor steelwork, 1 item @ £8,000 | |||

| Upper floors – 150mm precast concrete hollow core floor units (5.00 kN/m2), 500m2 @ £70 | |||

| Allowance for 75mm structural screed, 500m2 @ £30 | |||

| Padstones – allowance for lower ground floor, 1 item @ £1,500 | |||

| Allowance for timber framing to ground floor, first floor and roof, 1 item @ £140,000 | |||

| Roof | 117,700 | 81.51 | 3.7 |

| Roof tiles, including roof coverings, ridges, troughs, hips etc, 370m2 @ £80 | |||

| Double glazed rooflights and frames, including ironmongery, restrictors and vents, 12 No. @ £1,000 | |||

| Rainwater goods, 700m2 @ £20 | |||

| Man safe system, 1 item @ £7,500 | |||

| Parapet wall detail; aluminium capping, 40m @ £160 | |||

| Single ply membrane roof, insulation, vapour barrier etc, 340m2 @ £130 | |||

| Allowance for roof access hatch, 1 item @ £4,000 | |||

| Stairs | 25,000 | 17.31 | 0.78 |

| Main feature staircase incl. balustrades, handrails and half landings, 1 item £25,000 | |||

| External walls, windows and doors | 258,700 | 179.16 | 8.12 |

| Traditional external wall construction of medium quality facing bricks, cavity, inner blockwork skin and insulation, 740m2 @ £180 | |||

| Extra over wall tiles; including battens, 190m2 @ £80 | |||

| Extra over render; assumed two coats at 15mm thick, 180m2 @ £50 | |||

| Aluminium framed glazed system, incl. all ironmongery, 50m2 @ £450 | |||

| Double glazed windows and frames, incl. all ironmongery, lintels, restrictors and vents, 70m2 @ £380 | |||

| Window boards; 25mm primed softwood; one coat underseal and two coats gloss, 40m @ £50 | |||

| Main entrance aluminium double doors incl. all ironmongery; 1 No. @ £10,000 | |||

| Aluminium external doorsets, incl. all ironmongery, double, 4 No. @ £2,400 | |||

| Aluminium external doorsets, incl. all ironmongery, single leaf and a half, 12 No. @ £1,800 | |||

| Aluminium louvre douible plant room door and frame, incl. all ironmongery; fire rated FD60, 3 No. @ £3,000 | |||

| Internal walls, partitions and doors | 387,200 | 268.14 | 12.16 |

| 140mm thick blockwork partitions / metsec stud, 870m2 @ £60 | |||

| Metal stud internal walls; two layers of plasterboard to each side, 960m2 @ £85 | |||

| Internal glazed screens in softwood framing, 60m2 @ £500 | |||

| IPS panelling, one item @ £20,000 | |||

| Allowance for bed head trunking, one item @ £45,000 | |||

| Extra over for pattressing walls, one item @ £3,000 | |||

| Allowance for lintels to door openings, one item @ £5,000 | |||

| Allowance for single leaf timber doors, 40 No. @ £850 | |||

| Allowance for one and a half leaf timber doors, 55 No. @ £1,400 | |||

| Allowance for double leaf timber doors, 9 No. @ £1,800 | |||

| Allowance for single leaf glazed doors, 5 No. @ £1,600 | |||

| Allowance for double leaf glazed doors, 2 No. @ £2,600 | |||

| Extra over for fire protection (FD30), 1 item @ £10,000 | |||

| Wall finishes | 114,400 | 79.22 | 3.59 |

| Plaster to blockwork and skim finish to stud walls, 1,240m2 @ £15 | |||

| Allowance for splashback to wet areas, one item @ £2,000 | |||

| Whiterock to bathrooms, 780m2 @ £65 | |||

| 100mm skirting; one coat of underseal and two coats of high gloss paint, one item £2,000 | |||

| Allowance for sundry items [corner protection, handrails], one item @ £10,000 | |||

| Allowance to paint all walls with two coats of emulsion paint, 3,110m2 @ £10 | |||

| Floor finishes | 63,180 | 43.75 | 1.98 |

| Self levelling screed, 1,380m2 @ £10 | |||

| Heavy duty carpet, incl. underlay etc. 368m2 @ £30 | |||

| Altro vinyl sheet flooring with 100mm high coved skirting, 1,000m2 @ £35 | |||

| E/O wet areas, 110m2 @ £10 | |||

| Epoxy resin floor paint; Watco Dustop or equivalent, 12m2 @ £20 | |||

| Barrier matting - generally, 1 item @ £2,000 | |||

| Ceiling finishes | 89,100 | 61.7 | 2.8 |

| Taped and jointed plasterboard ceiling, 1,380m2 @ £35 | |||

| E/O for access panels to services, one item @ £10,000 | |||

| E/O for moisture resistant, one item @ £2,000 | |||

| E/O for fire protection, one item @ £15,000 | |||

| Decoration to the above one, 380m2 @ £10 | |||

| FF&E | 154,500 | 106.99 | 4.85 |

| Nurse base station, with built-in storage, three No. @ £6,500 | |||

| Shelving; generally, one Item @ £5,000 | |||

| Mirrors; generally, one Item @ £3,000 | |||

| Hand / grab rail; generally, one item @ £20,000 | |||

| Window blinds / curtain, one item @ £5,000 | |||

| Worktops, base units and the like, one Item @ £32,000 | |||

| Ceiling hoist track; one Item @ £50,000 | |||

| Staff lockers, one item @ £5,000 | |||

| Client and statutory signage; generally, one Item @ £5,000 | |||

| Sundry and fitting of Group 2 items, one item @ £10,000 | |||

| Mechanical installations | 405,250 | 280.64 | 12.72 |

| WC, 29 No. @ £650 | |||

| Clinical wash hand basin, 32 No. @ £480 | |||

| Wash hand basins, 29 No. @ £370 | |||

| Stainless steel sink kitchen sink with drainer, three No. @ £420 | |||

| Tea point, three No. @ £350 | |||

| Shower, with thermostatic mixer, 29 No. @ £1,000 | |||

| Sluice, three No. @ £3,000 | |||

| Installation of the above, one item @ £10,000 | |||

| Disposal installations, one item @ £80,000 | |||

| Water installations, one item @ £120,000 | |||

| Heat source, one item @ £30,000 | |||

| Space heating and air conditioning, one item @ £60,000 | |||

| Ventilating systems, one item @ £20,000 | |||

| Electrical installations | 617,100 | 427.35 | 19.38 |

| Electrical mains and sub-mains distributions, one item @ £70,000 | |||

| Lighting, one item @ £120,000 | |||

| Allowance for external lighting, one item @ £35,000 | |||

| Small power, one item @ £45,000 | |||

| Fuel installations / systems, one item @ £5,000 | |||

| Lift and conveyor installations / systems, one item @ £80,000 | |||

| Fire and lightning protection, one item @ £5,000 | |||

| Communication, security and control systems, one item @ £170,000 | |||

| External services, one item @ £10,000 | |||

| Testing and commissioning of building services installations @ 3% | |||

| Builders work in connection @ 5% | |||

| Preliminaries | 485,800 | 336.43 | 15.25 |

| Management costs, site establishment and site supervision. Contractor’s preliminaries, overheads and profit @ 18% | |||

| TOTAL CONSTRUCTION COST | 3,184,880 | 2,205.60 | 100 |

| (m2 rate based on GIFA) | |||

With thanks to Georgina Bishop, Andrew Rowland, Simon McLaughlin, James Wrixon and Sally Bateson from Compton Fundraising Consultants

1 Readers' comment