Five years on, Osborne’s axe has most definitely not been blunted

The last time George Osborne delivered a Comprehensive Spending Review, back in October 2010, the construction sector was under no illusion about the scale of the cuts to funding for the built environment that it would bring.

The government’s scrapping of more than 700 Building Schools for the Future projects and £230m of housing work before the chancellor had even stepped up to the platform had set the tone for what the post-election shift to an era of austerity would mean in practice. So when Osborne used his spending review to announce a 19% cut in departmental budgets over four years, together with the scrapping of a host of major schemes - the Severn Estuary tidal barrage, titan prisons and healthcare projects among them - the industry was left battered, but in no sense surprised.

Five years on, Osborne’s axe has most definitely not been blunted – and nor has his sense of purpose in using cuts to balance the UK’s books. But this time around, the industry as a whole seems much less exercised over exactly what Osborne’s speech will contain. And that may lead to some shocks when he delivers it in a fortnight’s time.

Even funding for some projects in the infrastructure sector – effectively the golden child of the government’s built environment policy – is looking under threat

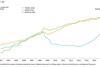

Given that the industry has, over the past five years, had to adjust to a much more constrained public spending environment, the lack of particular anxiety over what Osborne has in store for the next five is in many ways understandable - particularly as he has made it clear he will prioritise capital over current spending. But although the Conservative government is keen to present the policies it will set out as a continuation of its austerity drive, it is perhaps easy to overlook the fact that the spending review is not just more of the same lower departmental budgets. Rather it should be seen for what it is: another round of cuts that will reduce the cash available to several key construction spending departments significantly below even the austerity of the past five years. To inform the review, Osborne has asked most departments to model cuts of 25% and 40% over the coming four-and-a-half years. Both of these scenarios, in percentage terms, are a greater drop than those that helped scar the sector so deeply five years ago.

Of course, 2010 was then and this is now, and today the industry does at least have a recovering private sector construction market behind it to counter further drops. But with output statistics faltering over recent months, the prospect of further cuts to pipelines of government work has the potential to create another headache for construction firms just when confidence in growth is beginning to wobble.

Even funding for some projects in the infrastructure sector – effectively the golden child of the government’s built environment policy – is looking under threat. And even in areas like schools, which the government has promised will be protected from the coming reductions, there is still little likelihood of significant new programmes of work coming forward to meet the level of demand.

This is frustrating for a construction sector that, particularly given the ripples of concern over recovery, might well welcome the opportunity to spread some of its risk across long-term public sector programmes. But it is, of course, of even deeper concern for those within the departments themselves, who are tasked with trying to relieve pressure on the country’s already heavily burdened services - whether schools, housing or infrastructure - at a time of burgeoning demand and decreasing resource.

Against this backdrop, those running public sector construction programmes - including in the cities set to be granted greater devolved powers by the government - will presumably be particularly receptive to suggestions from industry over how to achieve efficiencies of scale, or new forms of public private partnership.

In that sense, the spending review could still open up chink of light for construction, where advice or prototype schemes could eventually build into a reasonable pipeline of work. But for an industry that still badly needs to be strengthened and buoyed, that’s pretty poor cheer.

Sarah Richardson, editor

![2753-KINGSLEYCLARKE-3377 (1)[11] copy](https://d3sux4fmh2nu8u.cloudfront.net/Pictures/100x67/1/1/2/2000112_2753kingsleyclarke3377111copy_616752_crop.jpeg)

No comments yet