Ike Ijeh considers an architect who managed to be both a humanist and a modernist

Oscar Niemeyer was the last of the generation of great Modernist architects who helped shape the world in which we live in today. The majority of his work may have been located in his native Brazil but the pristine, sculptural simplicity which became Niemeyer’s trademark helped define the Modern Movement for millions across the world. Like his contemporaries Mies van der Rohe and his idol Le Corbusier, Niemeyer’s architecture sought to overturn the unruly congested sprawl of the nineteenth century by creating a brave new world sanitised by efficient urbanism and rational design. But unlike Corbusier Niemeyer was a humanist, embellishing his buildings with a sensuous dynamism and fluidity of form that made them instantly comprehensible and humane in spite of their scale or significance.

Niemeyer’s most enduring legacy will be Brasilia, the new capital he co-designed in the 1950s and 60s and in whose virtuoso constellation of iconic structures we find the core ingredients of his architecture. Sepulchral settings, gleaming white surfaces, dynamic structure and sculpted geometric forms combine to create a theatrically choreographed urban tableau of awesome expressive power. Brasilia’s buildings also celebrate the chief instrument of Nieyemer’s artistry: the curve. Here we see planes and surfaces contorted into a sinuous terrain of flowing arcs and swollen nodules, each one not only humanising his buildings but also gracefully resonant of the natural, organic landscapes that Niemeyer constantly sought to evoke throughout his career.

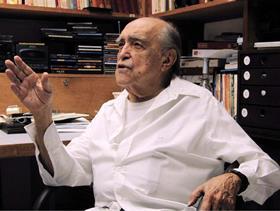

A significant part of Niemeyer’s legendary status was the fact that he lived and worked to such an advanced age. Wren lived to the age of 90 and Frank Lloyd Wright managed the grand old age of 91 but few architects ever managed to survive to within one week of their 105th birthday. Moreover he continued designing well into his nineties, completing one his greatest buildings, Rio’s Niterói Contemporary Art Museum, a spectacular white saucer sprouting mushroom-like from a reflecting pool cast precariously against a rocky gorge, at the age of 89.

Niemeyer’s inordinately long career is a symptom of his repeatedly attested true love, not architecture but life. It is this humanist grounding that enables Niemeyer’s work to effortlessly straddle the void between monumentality and intimacy, a notoriously difficult gap for most architects, even great ones, to breach. And for all the sculptural vigour and dramatic composition for which his work is rightly celebrated, it his fundamental interpretation of architecture through the lens of the human experience that will enable his legacy to endure throughout the many generations to come.

No comments yet