With tomorrow marking the 75th anniversary of VE Day, the efforts of firms like Higgs and Hill then is being mirrored by construction’s response now to the current crisis, writes Bam chief executive James Wimpenny

The 75th anniversary of VE Day is a bitter-sweet day. Bitter for those whose families lost loved ones. And relief, for the nation, that the great costs of the war eventually resulted in victory. The war we fought then has echoes today in the one we are all fighting against a more complex and elusive enemy. One common and perhaps surprising factor is the role that construction has played.

Today, our industry is building emergency hospital facilities across the UK. Back in 1943 and 1944, Higgs and Hill (H&H), the founders of our UK business, were asked to build three emergency hospitals, at Blockley, Gloucester, with 750 beds, at Foxley in Hertfordshire with 2,000 beds, and another near Hereford. How ironic to find ourselves 75 years later completing a new Nightingale Hospital to help our NHS ‘fight’ covid-19.

Our forebears had an extensive role in the war from the outset. By the time of the Blitz in 1940, H&H had built over 80 air raid shelters in London alone, and 20 static water tanks to assist the London Fire Service.

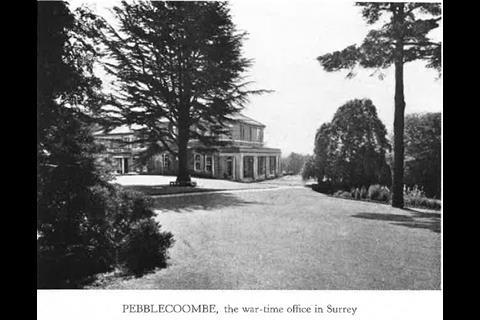

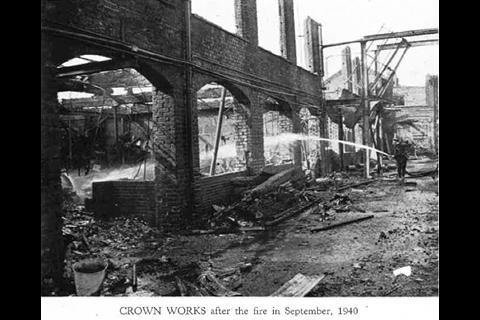

Our own premises, then in Vauxhall, were badly hit in a night time raid during the Blitz. We did not rebuild until 1947.

Removing bomb damage was an important duty for contractors: street clearance and temporary works was highly dangerous. Our teams were fully equipped on 24/7 standby and often arrived ahead of fire and ambulances in rescuing people from bombed homes.

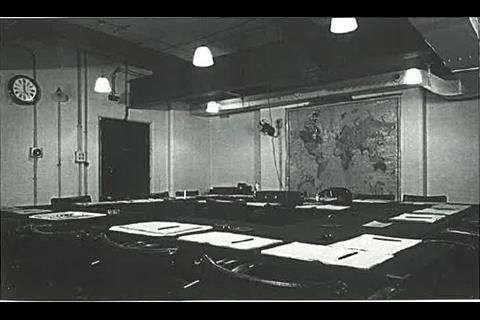

One special air raid shelter we built is widely known. Located on Charles Street it was called the Cabinet War Rooms and is now a much-visited museum attraction.

Another shelter we created protected the Speaker, the Prime Minister and Black Rod. It was soon tested: the House of Commons was bombed. The Speaker and his family – protected by our shelter - escaped uninjured. We reinforced the Commons roof using over 1,000 cubic yards of aggregate, 100 tonnes of cement, 800 sheets of corrugated metal and 300 gallons of aquaseal.

As a result of that event, we were commissioned to convert the ballroom of the Park Lane Hotel (which we’d built in 1927) into a new meeting chamber for the Commons. More “top secret” works followed. We built a flat in Curzon Street for use by the Royal Family and converted the basement of the American Embassy in Grosvenor Square. General de Gaulle led the Free French Forces from premises built specially by us in Carlton House Terrace.

Our biggest air defence scheme was the Citadel in Horseferry Road, accommodating government departments. A heavily reinforced, three-storey concrete structure with walls almost 10ft thick and a roof 11’3” in the centre. We sunk an artesian well 600ft deep, with diesel generators and built a sewage ejection plant. The independent telephone exchange was big enough itself to house a small town.

Working out of London on munitions factories (such as the massive Thorp Arch scheme in Leeds) and parts factories in the Midlands to supply the Halifax, Stirling and Lancaster aircraft, meant working closely with the government to get hold of the labour and materials which were closely controlled. Even drinking water could travel 20 miles to arrive.

No wonder we feel a certain pathos working alongside the Army today and in having Captain Tom Moore open our new hospital in Harrogate for Nightingale Yorkshire and the Humber.

We extended a lot of airbases across the UK (one huge one in Crimond, Aberdeenshire) and helped increase production of aircraft as well as providing munitions and parts. In 1941 the US joined the war and we worked into the night to create a control centre for them in an annexe to Selfridges. The Americans estimated three weeks to complete: we delivered in eight days.

Our largest scheme, Thorp Arch Royal Ordnance Factory close to Leeds, contained over 3,000 buildings, 25 miles of railway track, and took 6,000 men at peak to build, plus 3,000 more through subcontractors. The buildings could accommodate 18,000 workers who created 12,000 pound bombs.

When I began working for Higgs and Hill in 1987, on our ultimate journey to become Bam, we still had members of staff who had begun their careers working on Thorp Arch.

Perhaps the most striking job however was for the invasion of Normandy in June 1944. Along with other contractors, we prefabricated huge concrete floating harbours to enable the landings. They were known as Mulberry Harbours. We cast 100 large reinforced concrete anchors weighing 10 tonnes each to keep them in place during the Channel crossing.

We – the construction industry collectively – did our bit, as they say. Bam (as H&H) even raised enough charitable donations to fund a complete Spitfire aircraft, which joined the 349 squadron in 1943.

There are so many more schemes I cannot mention in such a brief piece but one I must is a premises we converted in Audley Street, London, which hosted the first ever meeting of the United Nations. That foreshadowed many years of peace to follow.

I hope, once again, that the collective effort and pain that our nation is enduring today, will also result in eventual victory. I am proud that the construction industry – then and now – has such an important role to play.

James Wimpenny is chief executive of Bam UK

Tell us about the projects that make you proud to help

Building has launched its Proud to Help campaign to highlight all the work construction is doing to support the country’s public services, critical works and supply chains, as well as setting it back on the road to recovery. Contact us at newsdesk@building.co.uk with the subject line ‘Proud to help’ or via LinkedIn or Twitter with your #ProudtoHelp stories

No comments yet