Some forms of renewable energy are unpredictable and not available at the right time - better implementation could reduce carbon emissions and save money

New renewable energy installations are often purported to be able to generate enough power for ‘X,XXX homes’. These figures are often impressively high but overlook the point that while these technologies may generate the required energy for those homes in total they will generate it unpredictably and you cannot have it when you want it. On a calm December evening for example wind turbines and solar panels won’t generate anything - just when most homes are reaching peak demand.

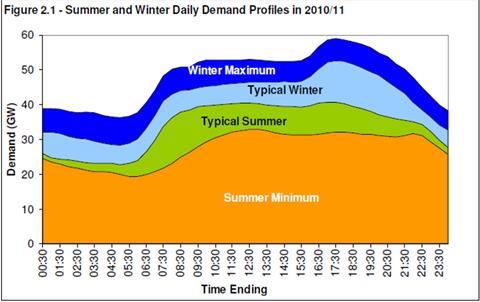

The way the National Grid works with a variety of different power sources – nuclear, gas, coal, renewables, pumped storage and international inter-connectors – means that broadly speaking the carbon intensity of our power (how much carbon dioxide is emitted per unit of power produced) increases the greater the demand (see graph below). When spikes of renewable energy are produced unpredictably, it is often lower carbon gas power generation that has to reduce production to accommodate it because carbon intensive sources are less easily ‘turned off’ at the drop of a hat.

Therefore if renewable power can be produced at times of peak demand, when we need it most, and exactly when it will be produced can be accurately predicted, it is far better.

At present the incentives in place, Renewable Obligation Certificates and feed-in tariffs, pay the producer the same amount per unit of power produced regardless of when or how predictably it is produced. So my first thought is, would it be better to reward power generation that is predictably produced at peak demand? Therefore actually providing more capacity, reducing the requirement for reserve demand and increasing carbon savings?

Just as a kWh generated at the right time can be more or less valuable, a kWh not used can be as well. A policy explored in a report by the UKGBC is the “Energy Efficiency Feed-n Tariff” or EEFiT. This looks at the potential to reward people for reducing their energy consumption, beyond the reduction in their energy bills. Surely if it is right that we pay someone 14.9 p to produce a kWh from a PV system it would be better to pay someone not to use that kWh in the first place, particularly at peak times. This is difficult to measure accurately. How do you know that they haven’t just been away with work, rather than turning off every appliance diligently?

Technology in the form of smart meters may incentivise reducing power consumption at peak times simply because the power will cost more then. Although complicated variable pricing for domestic consumers would be politically difficult, it has been trialled in other countries. Perhaps the commercial sector could take the lead here. We have had ‘Economy 7 electricity’ for a long time and contracts where industrial power users have contracts that agree they can be disconnected at times of peak demand but now there are opportunities to do this much more effectively.

It could be argued that we have already over-complicated the incentives and policies around power generation and consumption and the last thing we need is another layer of policy. However if implemented efficiently, recognising that not all kWhs are the same could reduce carbon emissions and save the state, business and individual’s money.

Barny Evans is

No comments yet