The astonishing tale of the Shropshire contractor and the stone worth somewhere between £11m and £100 has just taken another twist … Emily Wright talks to the man who has just bought it for £8,100

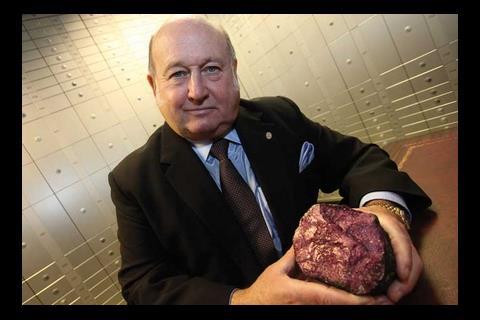

Just when you thought the story of the Wrekin ruby couldn’t get any weirder, the plot behind construction’s very own suspense thriller has taken another strange turn. After Ernst & Young found that Wrekin’s “ruby” could in fact be a lump of rock possibly worth £100 (see the story so far, right), it decided to auction it to Wrekin’s creditors. One of them, Tim Watts, a Midlands entrepreneur (pictured right), bought the stone for £8,100. And he is delighted with his purchase, because he reckons it’s worth £2m.

If Watts is right he will use the money first to plug a £120,000 hole left on one of his subsidiaries’ balance sheets – Network Construction Services in Telford was owed £120,000 by Wrekin when the firm went bust in March last year – and the rest will be donated to charity. The real plot twist, though, is how he will go about discovering just how much his recent purchase is worth: it is to be ceremoniously “cracked open like an Easter egg” at a special dinner for his board members.

The dinner menu

When Wrekin went under, it owed more than £20m to about 1,000 creditors, as well as another £20m to its pension fund. Along with the other creditors, Watts looked down the administrator’s list of assets. “There were all sorts of things on it, but I didn’t want a JCB. Where on earth would I have put one of those? But I saw the gem and recognised it would have notoriety value and could help plug the hole left by Wrekin. I thought it would be worth at least £10,000 so an £8,000 bid seemed about right. Even if we made £2,000 it would be worth it. I added an extra £100 in case anyone else had the same idea.”

Watts is the head of Pertemps, a £500m-turnover recruitment business, so he is in a pretty good position to take a punt on the stone. And punt it is: other than a shrewd idea of how much attention the ruby would win him, he didn’t know much else about it or its history – least of all the fact that it had been valued at £100. “I didn’t know that,” he says. “Although I think that is just facetious. I don’t believe that.”

Two weeks ago, he received a fax from Ernst & Young saying that out of 60 bids, his had been accepted. Before he knew it, the ruby was his and he “sent his chauffeur” to collect a black holdall from Ernst & Young’s Birmingham offices, and deliver it to the Birmingham Deposit Centre. Once safely transferred, Watts decided the time had come to take a look at construction’s equivalent of the Maltese Falcon.

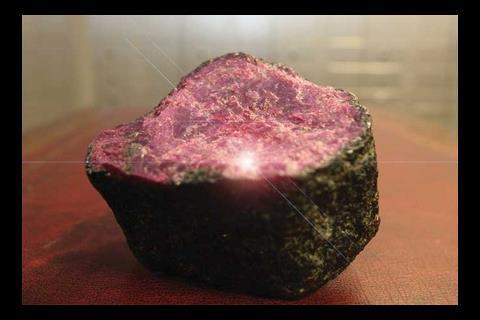

“I am not an emotional man,” he says. “But I must admit, when I first saw it I was wowed. It is the size of a football. I got a jeweller friend of mine to look at it and he instantly spotted around 20, beautiful deep red rubies on the surface. Now, they are going to be worth a considerable amount of money,” he says in a tone of voice that suggests he is making a statement of fact. Indeed, he says that, based on his friend’s valuation, the ruby could be worth anything between £300,000 (which is what the ruby was valued at in 2007) and £2m.

But he concedes the only way to know for sure will be to bring in an expert: “We have identified that we are in need of a gentleman from a mining company in South Africa to come and join us at a dinner event to take it apart. We will have a little meal for the board of directors, with a bottle of 1948 ruby port which we still have in the cellar, and he will sit and chip away all night and we will watch the rubies fall out like pomegranate seeds.”

And his confidence is unwavering. When questioned on whether the stone will prove to be as valuable as he believes, Watts shoots back: “I am sorry, but did you not hear me earlier? Twenty beautiful dark red diamond rubies on the surface, I said. We’re looking at £100,000 at least and anything extra on top of that will go to a Birmingham charity. If a heart-shaped ruby happens to fall out then I will give that to my wife. “But the main priority is to plug that gap in Network Construction Services’ balance sheet.”

If Watts is right, and the tale of the Gem of Tanzania takes another extraordinary turn, it will be some compensation for the damage that the Wrekin affair has done to his business and the people who run them, but bad feelings will inevitably remain.

Sandy Palmer, managing director of Network Construction Services, describes his experiences of dealing with Wrekin in the months leading up to its collapse as a nightmare. “In the January before Wrekin went into administration we had already removed all of our staff and labourers from their jobs,” he says. “But we had been working for them for about 12-18 months up until that point and then began to find it harder and harder to get paid for work.”

Palmer says he and his director of operations were twice forced to make personal visits to Wrekin’s head office to demand payment. Palmer says: “He just kept saying ‘these are difficult times’ and we would say ‘yes, we know they are difficult for everyone – and this is our money, not yours.’ Each time he eventually wrote us a cheque: one was for about £70,000, the other for around £140,000 and they cleared, but they were six months overdue.”

When the firm went into administration, Network Construction Solutions was owed £120,000 and Palmer says he will continue to feel let down whatever the ruby is worth: “How would you feel if I owed you £120,000 and then sloped off? We supported that company, I was always there to help when Wrekin needed staff through the night to finish jobs they were behind on and a gem is no substitute for that.”

And Palmer is not convinced the ruby will be the answer to the company’s financial gap. “There will be some added value but not very much I wouldn’t have thought. I sit on the creditors’ committee and Ernst & Young have made it quite clear that it is very unlikely there will be any money to pay back anyone.”

The story so far …

When Wrekin Construction, a mid-sized Shropshire builder, went into administration in March last year, it made national news. The firm said it still had £1.5m of its RBS overdraft, but it had been frozen by winding up petitions, and the bank was unwilling to lend any more to assuage creditors. So here was another example of the banks crushing a perfectly good business; 600 jobs were likely to be lost.

Then an accountant examining Wrekin’s books noticed that its principal asset was something called The Gem of Tanzania – a 2kg ruby with a value of £11m. Without that, the company was in a much worse position than it appeared. But £11m would mean it was worth £8.4m more than any ruby in history. And where had it come from anyway?

In 2007 Wrekin was struggling for survival after an expansion plan went wrong. David Unwin, a local entrepreneur who owned a property company called Tamar, bought it, and used the Gem to return it to solvency. The problem was that the Gem was valued at £300,000 on Tamar’s sheet and £11m on Wrekin’s. Then it was revealed by the BBC’s Inside Out West Midlands programme that Unwin had received a 12-month suspended sentence in 2002 after selling £1.2m worth of construction plant that was not his. The programme also uncovered that fact that 30 other firms run by Unwin had gone into administration or liquidation.

So what was the “ruby” worth? Ernst & Young, Wrekin’s administrator, asked an expert, who told it the gem was in fact a lump of metamorphic rock called anyolite which may have a market value of about £100 …

No comments yet