Have you ever been tempted to tweak the books a bit? Don’t. Read this cautionary tale aboout a developer who felt hard done by when his houses slid down the hill

You can’t help feeling a twinge of sympathy. The judge found this chap to be an honest witness, intelligent and astute, an experienced developer. But in law what he did amounted to dishonesty. He had to fork out £154,577 from his own pocket, plus the costs of the trial and costs in the Court of Appeal. On top of all that, his houses on the development had slid down the hill.

I’m telling you this story to get you to mind your Ps and Qs about compiling accounts, or not paying or short paying accounts.

The first owner had suffered no substantial loss, but he wanted half the damages once the developer had won the case. The deal was described as having the developer over a barrel

The building site is in Hythe in Kent. The owner sensibly engaged geotechnical experts who gave the thumbs-up for a number of two-storey houses. The owner sold the site for development. The developer engaged a contractor. Phase 1, up the hill, went well. Phase 2 was interrupted when the houses up the hill started marching down it.

The builder eventually went broke. The folks nearly on top of the hill sued the developer. The developer had no contract with the geotechnical experts so he asked the original owner to assign the geotechnical services contract to him. That’s because he had obtained the soil reports at the outset, relied upon the advice therein and wanted to sue.

The assignment had a price: to divvy up the damages with the first owner. That deal was described in court as having the developer over a barrel. The first owner had suffered no substantial loss, yet he wanted half the damages once the developer won his case. Which he did, though it went to the Court of Appeal to decide if the assignment entitled him to sue the geotechnical folk. Later a secret compromise deal resulted in the geotechnical firm stumping up the cash. The developer put £309,154.98 into his company’s bank account.

By now the developer company was insolvent. Of that £309,154.98, half was to go to that first owner and meanwhile be held in trust. But the developer’s managing director, and sole owner, decided to pay out the whole of the £309k to six creditors, including his bank, his joint venture companies, his lady “life partner” secretary and himself. There was nothing left to go to the first owner.

When the first owner sued the developer in person for “dishonest assistance” in defeating the trust and seeking restitution of the cash, the judge decided none of this was dishonest. The Court of Appeal carried out a careful analysis of what conduct amounts to dishonesty. It reversed the first judge.

Imagine you are tempted to inflate an interim account valuation to more than you are entitled to, or to issue a payment advice or certificate for a sum less than the other chap is entitled to. Imagine you are making a claim for disruption and building a file of time sheets to prove your case. Imagine you are finding defects in the works and making a meal of the costs for correction. Imagine that file of day-work sheets isn’t quite as authentic as might represent the truth. Dishonesty? Personal liability?

It’s interesting that the first instance judge got his understanding of law of dishonesty wrong. He accepted correctly that our man had assisted in the commission of a breach of trust; he had deliberately paid the money in trust to other creditors. He did so, said the judge, because he felt the first owner had taken unfair advantage of him. But the judge said dishonesty, while having an objective test - “conduct which would be regarded as dishonest by any right-thinking person” - also had a subjective element whereby some might think the conduct dishonest and some might not. In which case the defendant is not liable for dishonest assistance.

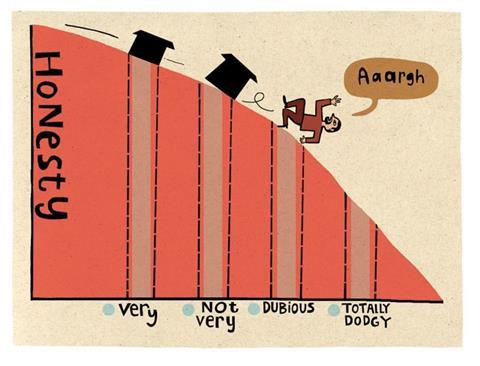

No, no, says the Court of Appeal. Honesty is not an optional scale, with higher or lower values according to the moral standards of each individual. If a person takes another’s property, he will not escape a finding of dishonesty simply because he sees nothing wrong in such behaviour. The subjective task is to look at each element of the transaction, then ask objectively if it transgresses ordinary standards of behaviour. Here the element was a plain intention to defeat the just claim of the creditor and that does not meet the standards of honest behaviour. If I deliberately underpay you, if I inflate my invoice, that is dishonesty and I am liable. Watch out for those day-work sheet records!

Tony Bingham is a barrister and arbitrator at 3 Paper Buildings Temple

No comments yet