Scott Brownrigg’s Neil MacOmish dreams of ways we can watch live sports in venues once again

News has just broken regarding the change in lockdown restrictions in England, limiting social and leisure contact to bubbles of six people, either inside or outside. The statement says that is not applicable to ‘organised sports’, but is unclear on whether this is for spectators or participants. Many questions remain.

These changes may, on the face of it reverse recent aspirations on trying to return crowds to stadiums. Here lies one of the problems for designers and managers of stadiums now or in the future: understanding that while the current pandemic, being the most serious in 100 years, is very unlikely to be the last. How does architecture and the built environment respond so quickly to such rapid change?

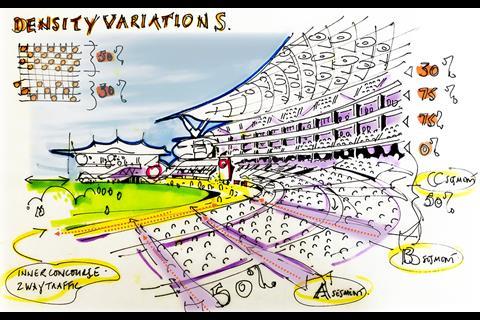

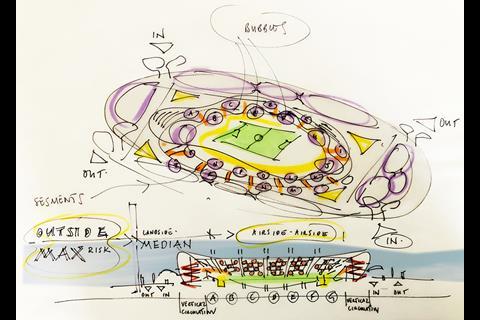

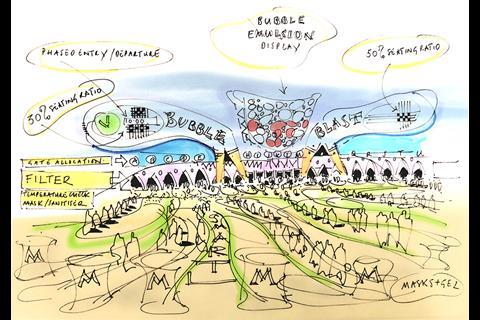

We can look at all the current pragmatic responses to facilitate spectators back in our sports arenas: masks, staggered arrival and departure times, maintaining social distance and a raft of technological developments that may or may not be implementable. Each has subsequential consequences. Keeping 2m of distance, on average, reduces the total capacity by about 73%. Even changing this to 1m still reduces the total capacity by about 57%.

The economic consequences to sports clubs and venues are obvious and, while public health and safety must be the major consideration, there are further considerations on the benefits of mental wellbeing of social contact and shared events, let alone the £24bn-40bn contribution the sports industry makes to the UK economy.

I yearn to watch live sport again. I even yearn to see audiences back in filled stadiums in real life and on TV. I was satisfied for a little while with the piped crowd noises on TV, but no matter how clever the connected sound might be (algorithms and pixels from the gaming industry), the irony and balance of noise from Home and Away supporters is not equal and not really reflected. Two of my colleagues hate the piped ‘fake’ crowd noise currently being aired, but they are a Crystal Palace supporter (whose fans are known for being exceptionally vocal) and Norwich (whose fans are not – famously called-out by their chair, part owner and TV chef, Delia Smith at half time “where are you? Let’s be ‘aving you”), which suggests that this is a quintessential part of the theatre. So ideas of further augmented reality – projecting fans onto blank screens, green seat technology, simply doesn’t create the same theatre as watching people bite their nails with 10 minutes left to play, collective tears on relegation, screams of joy and embraces in winning at the last minute or with the last ball.

Even watching the recent game that allowed a partial audience into the Amex stadium, just looked, sounded and felt like that no one really bothered to turn up

There are two participants in the overall theatre – those on the field of play and those watching. The augmented reality thing might work as you exit the Haunted Mansion in Disney World (two ghosts sit beside you on your seat as you leave), but it does not cut it as part of the authenticity of sport. When the Indian Premier League first started, Test Match audiences in India dropped in numbers significantly – “who cares” was the response, “we have the TV money”. Unfortunately, the TV companies cared. Televising games with no crowds was not good TV, so the authorities had to act. Even watching the recent game that allowed a partial audience into the Amex stadium (accepting this was just a test), just looked, sounded and felt like that no one really bothered to turn up. Clubs have tried photos of fans insitu, flags and inappropriate mannequins just to allude to the impression of spectators in seats. All of the above is evidence I would suggest, that this matters.

Returning to some of the potential pragmatics that may just help most, in terms of any necessary adjustments to current stadia are, primarily, technology driven.

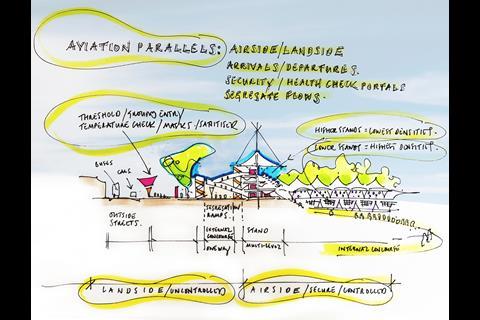

Temperature taking at the turnstiles, app technology, misting and UV(C) light in vomitories and on concourses are all-desirable if not essential. The fundamental tension that remains however is the one between moving large numbers and volumes of people yet maintaining safe distances.

Projecting such considerations forward to what new stadiuns might look like is equally difficult.

I thought of a stadium as a honeycomb in section – a series of individual cells, separate but linked – like a giant stack of Tokyo pod hotels. The issue with this is that the human contact is still detached. The experience might only be partially shared. When Aldo Rossi talked about our “collective memory”, he developed the notion of ‘shaping’: the combination of architectural form/space/place with event. He argued that for the environment to be meaningful, such interventions would build upon and share the collective memory, the layers of the city. It could be argued that to potentially satisfy the human condition, to complete the experience and ensure that we continue to bring on the next generation of fans, participants and a healthy nation, that these considerations are equally important.

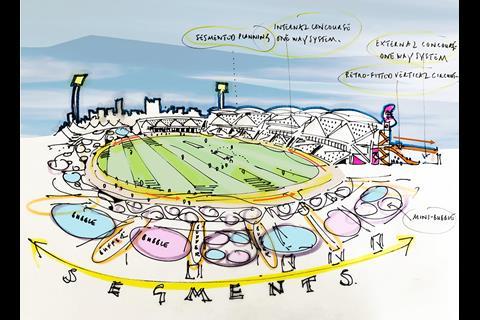

Perhaps then a better answer than a honeycomb might be the shared cells that can be seen in the interior of the Senate building in Star Wars (for those less familiar with the mega movie franchise, imagine hundreds of staggered opera boxes stacked above each other wrapping around a central stage or pitch). These fit American architect Robert Venturi’s criteria of ‘both/and’ rather than ‘either/or, - they are both individual but open and part of a greater collective.

It may be better to think about the complete theatre of experience – from the minute you leave your front door to the moment you arrive home

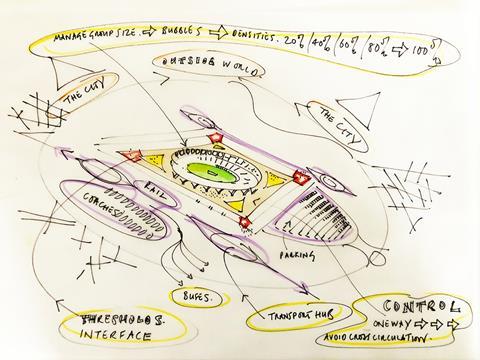

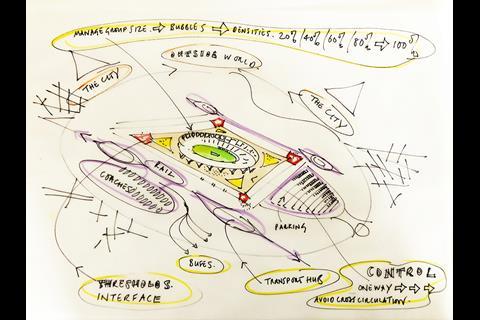

It may just be that the stadium alone cannot solve the conundrum of accommodating large numbers of people, but with a degree of necessary individual segregation. The frequency of interface may be just too difficult. It may be better to think about the complete theatre of experience – from the minute you leave your front door to the moment you arrive home. In referring to the crude diagram within the Safety at Sports Ground Act (the Green Guide), that looks at the zones of operation, perhaps each of these require specific and strategic intervention?

This might also be an opportunity for clubs to re-engage or augment their relationships with local communities – the processional walk to the ground rather than the same old stereotypical bowl in a sea of car parking on the edge of town, sustainable transport planning and programmes that extend the notion of the community hub.

I heard someone interviewed on TV who was attending the races at Doncaster (on the last day before the latest restrictions) say “I feel safer because it is organised”, implying that the experience had been ‘designed’. Not all of these issues are exclusive to stadiums; they have relevance to a number of public and civic buildings, spaces and places.

And strategic intervention in all parts of our built environment and fabric is something that architects and designers are really good at…

Neil MacOmish, board director, Scott Brownrigg

(Sketches by Alistair Brierley and Samuel Utting, courtesy of Scott Brownrigg)

No comments yet