The success of London's glossy Olympic bid presentation hinged on the city's ability to provide a legacy beyond 2012. So shouldn't we start doing something about it?

A fully paid up member of the sporting aristocracy has recently joined our management team. Sir Steve Redgrave has gained more consecutive Olympic Gold medals than anybody else in history and on more than one occasion I have sat back in astonishment as he has contributed to our development meetings.

However, Sir Steve is worried. He is not worried about the delays to Wembley stadium, nor about the future of Tessa Jowell, nor even about whether we will be ready for 2012. No, he is worried about what happens after 2012 when the Olympic flame is extinguished, the final chords of the closing ceremony have been played and the padlock has been placed on the gates of the Lord Blair Olympic Stadium. The issue of legacy is a bit like the elephant in the corner of a room that nobody wants to talk about. But at some point you have to consider the future after 2012 and use the impetus of the Olympics to drive forward improvements that last beyond a single event.

You may justifiably say our main worry is getting to 2012 with a credible, well funded, solvent Olympic project, not what occurs afterwards. However, with a white paper from the government before Easter promising enhanced funding for those needing to develop skills and a budget for Olympians from Gordon Brown we have only to keep our fingers crossed and our cynicism suspended and we have nothing to fear.

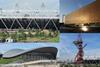

I believe that Sir Steve is better placed than most to voice a knowledgeable view of what the legacy issue is all about. He says a key to his vision of the future is the fact that the built facilities created for the 2012 Olympics are left as a usable legacy for all once the Games are over. In his view, in Athens the stadiums and venues were very impressive but they just weren't usable when the Games were over. Apparently it is not inspirational for an athlete to train in an empty stadium, even if its capacity is 80,000. But it would be a different matter if they were able to train in a 20,000-30,000 capacity venue that was also the home of British athletics, as well as a venue for schools and youth-level athletes. These facilities would more than achieve their original purpose. This is in our plan for 2012 and was accepted by those voting for our proposal last July - legacy was always in the mind of Lord Coe and his acolytes. It is up to us to turn that vision into a workable reality.

In Sir Steve Redgrave’s view, in Athens the stadiums and venues were very impressive but they just aren’t usable now the Games are over

Sir Steve also backs the idea of portable venues, which could be relocated across the UK after the Olympics have ended. Apparently, Paris has more 50 m pools than we have in the whole of the UK. Five training pools will be created in London but once the games are over they will be distributed across the UK ensuring everyone benefits (although, speaking for myself, when I jump off the high board I like to be sure that someone hasn't relocated the pool to Newcastle before I hit the water). And as it costs a lot of money to maintain these sorts of facilities, a 25-year wind-down of funding will be put in place to ensure these facilities remain open and become self-funding.

We are also trying to heighten the whole debate about building for a future that stretches beyond 2012. The 2012 Olympics can act as a catalyst for tackling a whole range of much wider challenges facing Britain and our industry today. There's a lot of enthusiasm from people about the Olympics and we should shape this to not only get the younger generation interested in lots of different sports but to look at related areas such as health, fitness, obesity and diet. The UK can be seen as a centre of excellence for an issue that is Europe-wide. Our Olympic facilities are within hours from Paris, Rome or Madrid. We have a chance with 2012 to develop a broader version of Center Parcs, encouraging visitors from all over Europe to see London and the UK as a place to have a healthy and fulfilling break beyond visiting Buckingham Palace and Madame Tussauds.

The document which laid out our winning bid was thousands of pages long and focused specifically on London - after 2012. The vision of schoolchildren presenting their image of what the Olympics will mean to them was a masterstroke of presentation worthy of a Lloyd Webber stage spectacular. Not only did it melt the resolve of the hard-hearted that saw Paris as the natural home for 2012 but it also staked our claim to be seen as the nation that was looking forward, not dwelling on past glories. At some point in the none too distant future we need to deliver on those dreams and ensure that legacy is not just confined to a long forgotten summary in a dust-filled bid document.

Postscript

Richard Steer is the senior partner at Gleeds

No comments yet