In an industry notoriously cautious of innovation, it’s quite something to meet a brickwork contractor who’s not only inventive but also prepared to see his inventions through

Liam Clear is no ordinary specialist contractor. He’s got more in common with Willy Wonka, the eccentric chocolate magnate in the children’s story Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, than with your average down-to-earth subbie. In Roald Dahl’s story, Wonka zips around his factory showing a group of children all sorts of weird and wonderful confectionary, while Clear darts around his industrial unit next to Wembley Stadium showing off his weird and wonderful inventions made from concrete and steel.

Clear heads Pyramid Builders, a brickwork specialist that is bucking the downturn. He employs 170 people, compared with 150 three years ago at the height of the boom, but even this isn’t enough. “I am turning work down and have been for the last three months,” he beams. “Everyone keeps going on about the recession, but this is the busiest year I’ve had in 25 years of trading.”

The reason Clear is doing so well is because, like Wonka, he is an inventor who is prepared to take risks to see his ideas through into commercially viable products. Clear reckons Pyramid Builders will turn over £7.5m this year. Wembley Innovations, the Wonkerish part of the business, will turn over £1m on the back of something called the Wi Beam - an innovation that eliminates the need for lintels over windows and the steel columns needed to give walls extra stability.

Clear has also developed a platform access system called Safestand which he hires out to contractors. This part of the business will turn over £2m.Clear reckons about half of Pyramid Builders’ turnover is down to installing Wembley Innovations’ products, which means these ideas make up nearly two-thirds of total business turnover. He won’t talk precise figures, but says profits are ploughed back into product development and, overall, 40-50% of the profits come from his ideas.

Getting to this point has been difficult and expensive. There are development and patent fees, then contractors want guarantees in case of problems, and public indemnity cover. Getting a new product on site is horrendously difficult,” Clear says. “It has to be cheaper than my competitors; I have to do the design then provide the warranties and public indemnity insurance. You can see how much it works against me.”

Now, though, the Wi Beam has gained widespread acceptance, including being used on the aquatics centre and six of the blocks of the Olympic village, plus the new campus for the University of the Arts London at King’s Cross, which will house Central St Martins College of Art and Design.

Having got this far with the Wi Beam and sister product the Wi Column, Clear now has major blockwork manufacturers biting his hand off to produce and market the system under their own name. The reason is simple, he says. There is only 0.5p profit on a standard concrete block, but 7p for the special blocks needed for the Wi Beam system. The interested companies, Hanson and Tarmac, have even prepared glossy launch brochures in the hope they will get the exclusive deal to sell the product.

But Clear isn’t rushing to sign up because he doesn’t feel either manufacturer has made life easy for him. Until now he has had Hanson, Tarmac and small blockwork maker Plasmor manufacturing the blocks, structural support system maker Halfen making the steel components, with Pyramid Builders itself installing the system. Clear paid for the moulds used by the three different manufacturers as this meant he retained control over the system. He shelled out £100,000 for the moulds used by Hanson, but the firm has now said it is closing all its plants in south-east England, so his investment is sitting idle.

Clear says negotiations with Tarmac over the rights to the system have been painful as it insisted on lawyers being present at meetings, which has added up to a £50,000 legal bill. He says Plasmor is very good but hasn’t decided whether it wants to be in the running to market the system. He adds that Halfen isn’t being pro-active either. As a result he wants to involve a non-UK-based manufacturer that could make all the components before deciding who to go with.

The Safestand access business is doing well but suffers from a different set of problems. Clear darts over to another area in his unit where the system is set out in several neat rows. He points out that only one of them is the genuine article; the rest are copies. “They couldn’t even be bothered to change the colours,” he says in disgust of the most recent pretender. He spent £150,000 fighting off this particular would-be competitor, which understandably rankles. “The onus is on us to prove they copied our product which means we have to bear all the costs,” he says.

If you have an idea, give it to your guys on site and see what they do with it. it never comes back the same and is usually better

Liam Clear, Pyramid builders

These rival systems use bandstands, a simple type of adjustable trestle on which scaffolding planks are placed. Safestand is a more finely engineered system that cost £1.5m to develop. The telescopic elements which allow it to be easily adjusted feature very fine tolerances which contribute to its stability. Clear had to get square hollow steel sections specially rolled to achieve what he wanted. The reason so many people are trying to copy Safestand is because many main contractors, including Bam and Kier, will only allow approved scaffolders or Safestand to be used on their sites.

As getting products to market is such hard work, why does Clear bother? Another corner of the industrial unit offers some answers. Here, several sections of metre-high blockwork wall topped with coping stones are being sprayed with fine jets of water. It’s the cracks in the mortar joints between the coping stones that bother Clear. “Why buy a nice, natural stone coping and put a horrible joint in the middle? The joints inevitably crack and water gets in every time,” he says. “I want things to be perfect.”

His first stab at a solution was a standard coping stone with a special jointing detail which drains the water away from the centre of the wall. The coping stones are dry jointed which looks neater and there is nothing to crack. But this wasn’t good enough for Clear, so he developed a coping stone with a curved top which acts like a gutter. Water is funnelled along a parapet and into a drain like a gutter. The advantage of this is that water can’t pour off the edge of the coping stones and wet the outside of the wall, and the water can be harvested too.

But the main thing that motivates Clear is that he wants to be known as the legacy man. “Money doesn’t really interest me,” he says. “I want to make a difference and leave something behind, something that makes the industry better and safer.” Clear says he doesn’t want to expand his firm to take advantage of all that work he is turning down. “I don’t want to be the biggest but I do want to be the best,” he says.

What advice does he offer specialists who want to come up with a recession-beating innovation? “If you have an idea, give it to your guys on site and see what they do with it,” he says. “There’s a lot of talented people out on site whose creativity is buried. See what they do to your idea, it never comes back the same and is usually better.”

One corner of the Wembley unit is cordoned off because of something “a bit sensitive” in there. What will this extraordinary specialist contractor and his team come up with next?

What is the Wi Beam?

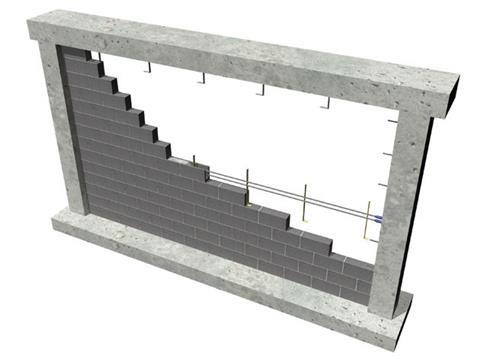

The Wi Beam (pictured above and left) arose out of Liam Clear’s dislike of the windpost, a vertical steel column inserted into long runs of blockwork to give walls greater lateral stability.

“You’ve got to manoeuvre a 500kg windpost into position then put up scaffolding to fix it at the top,” he says.

“You then have to put in ties to link the windpost to the blockwork and cut the blocks to fit around the windpost. The gap between the blocks and the post need filling, then you need to fit fireproof board over this, then with the differential movement you get cracks.”

The Wi Beam gets rid of all the above, which adds up to a 15% time saving.

It also eliminates risky heavy lifting, including the need for weighty lintels over openings. It is basically a reinforced concrete beam running the length of the wall at regular intervals to give it the necessary stability.

Specially made U-shaped blocks are placed onto the course below. Special brackets link the Wi Beam to this course and also help locate and provide the correct spacing for two lengths of rebar running horizontally through the special blocks.

The rebar is secured to dedicated brackets at the ends of the walls and concrete poured into the U-shaped block locking the block and rebar together.

The spacing of the beams varies according to the loads on the wall; openings are catered for by running the beam in place of the lintels.

Clear has come up with two other innovations. The first is a conventional block with slots in the top and base which means it bonds better with the mortar above and below.

Until recently the beam was attached to conventional steel or concrete posts at the ends of the wall, but Clear has developed a vertical version of the Wi Beam which does the same job. He has even produced a specially coloured mastic invisibly to seal the joint between the column and the rest of the wall.

No comments yet