If London is to host an Olympics without white elephants or black holes, the procurement routes must be chosen with great care. These are the contenders

The idea of an Olympic legacy was pivotal to London’s successful bid for the 2012 games. Large parts of London are to be regenerated, sports and other facilities are to be created and investment in infrastructure is to stride ahead. Yet while we ponder the vast sums to be ploughed into creating that legacy, the question is, how can the money best be spent?

The government, which is by far the biggest source of construction spending, has invested substantial resources in procurement. It wants to get value for money, and to be seen to be getting it, partly by streamlining the way it procures. The Treasury has provided guidance on the suitability of the PFI as a procurement model for projects, taking into account value for money and the proportionality of transaction costs.

The Office of Government Commerce has also produced Achieving Excellence in Construction, a best-practice guide for government departments on procuring public works. When talking about procurement strategies, it is quite clear that the OGC is shying away from traditional procurement and construction management (and variants such as management contracting) in favour of other forms – particularly design and build.

Some say this approach is too restrictive; others that it is good government. Yet as taxpayers, we all wish to see our money well spent. For the Olympics we certainly want to avoid the sort of controversy that occurred on large British schemes such as the Scottish parliament and the Millennium Dome, or the reported mayhem in Athens during the run-up to last year’s games. No white elephants and no black holes.

Of course, there is an enormous amount of engineering work, such as infrastructure, remediation and river engineering, to be procured in the lead-up to the Olympics and this work rarely lends itself to design and build. Here, traditional procurement is in its element. Ground conditions, pollution and contamination are not factors that any contractor can easily price for, and few in the current market will be prepared to take a gamble by doing so.

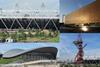

Contrast this with building work, where there are more opportunities to transfer design and construction risk sensibly to contractors. Notable examples include the 80,000 seat Olympic stadium, the aquatic centre, the velodrome and the Hackney centre, not to mention the Olympic village. In taking a holistic approach, there is merit in seeking a balance of risk across the works to be procured.

You might think that when it comes to matters that involve so much national pride, everyone should be pulling together. But this is where it might get interesting. Certain players in the industry will already be whispering in powerbrokers’ ears about how best to deliver the 2012 games. In doing so, some will be talking up the merits of construction management.

Construction management, so the mantra goes, will allow for works to progress while design is developed and subsequent works let. If managed properly, costs can be controlled – indeed, there are savings to be made – and works procured more quickly.

But under this form of procurement, construction managers do not have responsibility for design or workmanship, nor do they have to procure the works on time or for a given price. And if things go wrong with construction management, it can be disastrous. Trade contractors bring multiple claims for prolongation and disruption, preliminaries escalate, and the construction manager charges additional fees as the project stutters along. The case of Great Eastern Hotel vs John Laing this year did provide a yardstick for construction managers’ responsibilities, but there are risks nonetheless.

Some may reel off a list of successful construction management projects as long as John Prescott’s prodigious reach but construction management for the Olympics should only be used when it is clearly the best way forward. It would require the brief to be clear and unwavering and to have a chain of command that is streamlined, knowledgeable and autonomous. Any client that doesn’t know enough about construction management – or worse, thinks it knows more than it does – is asking for trouble.

Postscript

Matthew Jones is a construction lawyer at Travers Smith, matthew.jones@traverssmith.com

No comments yet