Last week’s report proposed root and branch reforms - now industry and government must come together to bring about real and lasting change

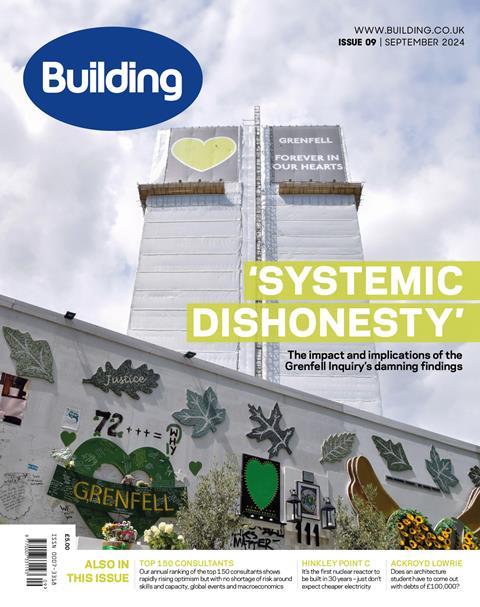

Over the summer the construction industry had been bracing itself for 4 September, the date when the inquiry into the Grenfell tower fire which killed 72 people published its final report. Sir Martin Moore-Bick and his inquiry panel concluded what we already knew: every single one of the deaths – 54 adults and 18 children – was avoidable.

The report pulled no punches. A lethal combination of dishonesty, deregulation and incompetence on the part of industry and government over a matter of years led to combustible cladding being installed on the tower.

There were multiple opportunities to prevent the disaster that unfolded on 14 June 2017. And yet at every turn individuals who could have made a difference made flawed decisions with disastrous consequences or turned a blind eye when the dangers were staring them in the face.

Anyone who had followed the inquiry hearings in the seven years since the fire knew the damning evidence that underpins these conclusions. That did not lessen its impact or make it any less sickening to read. In black and white, and over nearly 1,700 pages, it has laid bare the extent of the failures.

The inquiry’s criticism was levelled at many different parties: the government, Kensington and Chelsea council, the tenant management organisation, the product manufacturers, the certification bodies, the testing house, the architect, the contractor, the subcontractors, the fire engineer, the local building control department, and the London Fire Brigade.

Worse still, the inquiry said the regulatory system supposed to prevent a fatal event such as this was “seriously defective” and the statutory guidance “poorly worded and liable to mislead”.

Successive governments missed opportunities over decades to identify the risk of combustible cladding. And under David Cameron’s premiership, a deregulatory agenda seemingly became more important to civil servants than preserving life.

Progress has been made but the question “is it enough?” must never fade. There is no quick fix or end point to creating a building safety culture

Having outlined failures on such a scale, it is not surprising that the report’s recommendations are also wide-ranging. Its authors – aware that Grenfell is the most catastrophic but by no means an isolated case – clearly believe root and branch change is now needed.

The government is not due to formally respond to the report for six months, but it has taken some steps already, declaring that it will bar companies criticised in the report from public sector contracts. It has also said it will speed up the remediation of the 4,630 residential buildings over 11m still blighted with unsafe cladding.

Keir Starmer’s speech on the day of the report, which he described as “a long-awaited day of truth [that] must now lead to a day of justice”, suggests the prime minister will be sympathetic to many of the proposed reforms.

>> Also read today’s analysis: ‘We will deliver a generational shift’… Why the Grenfell Inquiry report means another building safety shake-up

There will and should be debate about which recommendations are taken forward and how. Some industry voices have broadly supported the headline proposal for a single regulator overseeing the whole of the construction industry – from products, to building control, to contractors and much more. This would be a vastly expanded role to the current Building Safety Regulator, which many we have spoken to feel is already struggling to fulfil its workload with the resources it has.

There is a fear that such a move could hold back the progress being made with the new structures and systems brought in by the Building Safety Act 2022. In other words, we need to watch for unintended consequences before we radically change tack.

A proposed licensing regime for contractors has also raised questions, particularly the suggestion that a company director or senior manager makes a personal undertaking at the gateway 2 stage in a project to ensure the building is safe on completion. The pool of contractors that work on higher risk buildings is already small, this could reduce it still further.

With higher quality and more stringent regulations comes higher costs. That may be no bad thing. Construction firms that care about quality and safety want standards raised, they want more money spent on training, competence and qualifications because this would weed out unscrupulous companies winning jobs on the cheap.

Further change is inevitable. Dame Judith Hackitt herself said last week “we are on a journey and there is still a long way to go”, underlining that real change stems first from regulatory reform and secondly from a cultural shift within an industry.

More on the Grenfell Inquiry Phase 2 report

Product manufacturers come out fighting after Grenfell Inquiry’s damning verdict

What the Phase 2 report said about consultants and contractors

Grenfell Inquiry Phase 2 report: all our coverage in one place

Decades of central government failure led to Grenfell tragedy, says inquiry

Company bosses must lead this culture change and start to repair the damage. Construction’s reputation is in complete tatters. People hear about widespread malpractice, firms sacrificing people’s safety for profit, exploiting loopholes and subcontracting work to dump risk and avoid accountability. They rightly conclude that construction has lost its way, its sense of purpose.

Moreover, construction is not known for having a sense of psychological safety that would make employees unafraid of reporting failures. This too is something that must change. When everyone takes responsibility, no one is able to pass the buck. No one can say they did not feel able to speak up when they witnessed unethical or dangerous behaviour.

In terms of what went wrong on the Grenfell refurbishment project, we now have all of the awful truth. An entire industry has lessons to learn. Progress has been made but the question “is it enough?” must never fade. There is no quick fix or end point to creating a building safety culture, it is a continuous process that takes time and money.

Chloë McCulloch is the editor of Building

1 Readers' comment