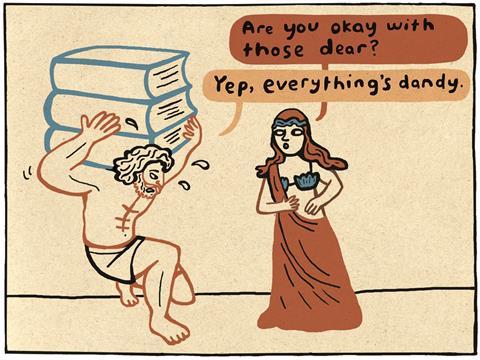

New tomes on construction law and Scottish arbitration are well worth picking up - if your back can take it

If I said “wow” once, I said it three times. Construction Law, by Julian Bailey, (Informa Law, £425) is a massively welcome, jaw-dropping endeavour of 2,000 pages over three volumes. The foreword by Court of Appeal judge Sir Rupert Jackson is worth repeating: “This is no ordinary or pedestrian book on ‘building contract law’. It is a tour de force.” He predicts it will quickly become a standard work of reference for busy practitioners. Later, I will pick a fight with the publisher.

The everyday experiences of building buildings in Perth or Melbourne is almost identical to the highs and lows in Shepherd’s Bush or Aberystwyth

Bailey is a construction lawyer at CMS Cameron McKenna in London. Previously he practised in Sydney. His experience in both Australia and England has added enormously to this book and elevated it to a very special level. The big advantage here is that the everyday experiences of building buildings in Perth or Melbourne is almost identical to the highs and lows in Shepherd’s Bush or Aberystwyth. And the enthusiasm to go legal in both is almost identical. More than that, the respect that the two legal systems command is a gold mine for the canny practitioner who might, just might, spot an angle developed 11,000 miles away about a building dispute that gives him an edge.

The three volumes are focused on principles rather than cases, the foreword says. At which I blinked. Astonishingly there are 7,000 cases in the table of cases. On top of that is a table of statutes, then statutory instruments.

Ah, then we get to those principles, and to a pulling-up by the author. He says there is no such thing as construction law. Well, perhaps nowadays there is a glimmer of a category. Neatly, he says the world of construction and engineering law has become developed; with relief he adds, “and more complicated”. He points to the elaborate contract documents

(I call them idiotic), containing dozens of intricate clauses and a maze of provisions. I began to like his fractionally irreverent style.

His main focus is law of contract, the tort of negligence, especially in the professional arena, analysis of legislation and principles of equity. Let’s see how deep the book goes on those few principles. The sections are familiar. “Contract Formation” is a mini textbook (50 pages). “Contract Terms” is a magnificent 100-page analysis. The part about implied terms is so clear and neat. “Procurement” nearly draws a criticism from me about the paucity of analysis of letters of intent. But the author’s footnote takes me to a whole pile of learned writings by others.

I cannot carry three very heavy volumes around with me. Please put them on a CD … a searchable gizmo for my laptop. I want Bailey on my knee

Bailey’s research is overwhelming in its scope. “Contract Administration” includes at least a nod in the direction of the project manager’s role under NEC, and then the sections go on to payment, control of variations, the site, breach and termination. And there is so much more … negligence, time control, damages. Bailey goes on and on.

But - and this is my fight with Informa Law - I cannot carry three very heavy volumes around with me. Please put them on a CD … a searchable gizmo for my laptop. I want Bailey on my knee … Informa Law, across my knee.

My second book is Scottish Arbitration Handbook by David R Parratt and Peter Foreman (Avizandum, £95). It is timely. It begins: “The Arbitration (Scotland) Act 2010 has dragged arbitration law in Scotland into the modern era.” At last, I added.

Candidly, the authors admit that if Scotland has the creditworthy ambition of making itself an international arbitration centre, the arbitrators will have to show that the act actually works. What they are driving at is that it’s no good having this excellent machinery if the practitioners get in the way of those who have the will and enthusiasm to operate this new machine. Sparks fly when practitioners are heaved out of their familiar rigmarole for something new.

The new bit is the relationship between the practitioners and the courts. Gone is case stated, gone too (hooray) is the risk of intervention of judicial review. In essence the book explains how the new act has been modelled on the English Arbitration Act 1996 and how to operate those rules, explained by two active arbitrators. This act gives the tools to the arbitrator to provide much greater economical and private arbitration to commerce in Scotland. Let Scotland show us how to make it a success.

Tony Bingham is a barrister and arbitrator at 3 Paper Buildings, Temple

No comments yet