Ten reasons why the 32-year construction of the Houses of Parliament did not run smoothly

In light of the recent news that the Houses of Parliament could close for a £72m upgrade, we decided to take a look back at what was historically a long and very problematic construction project.

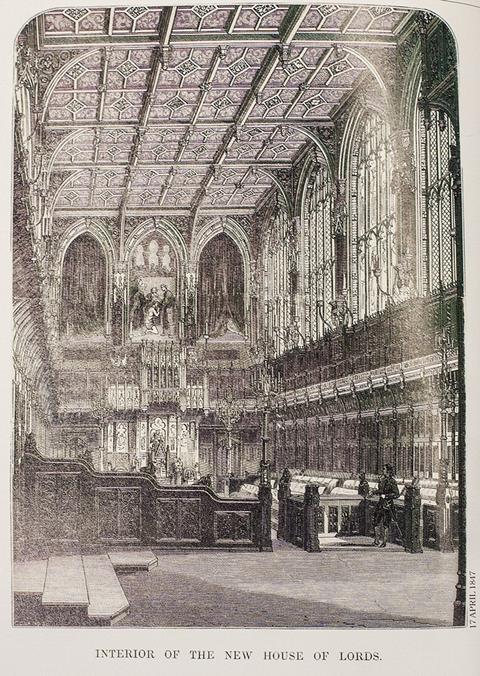

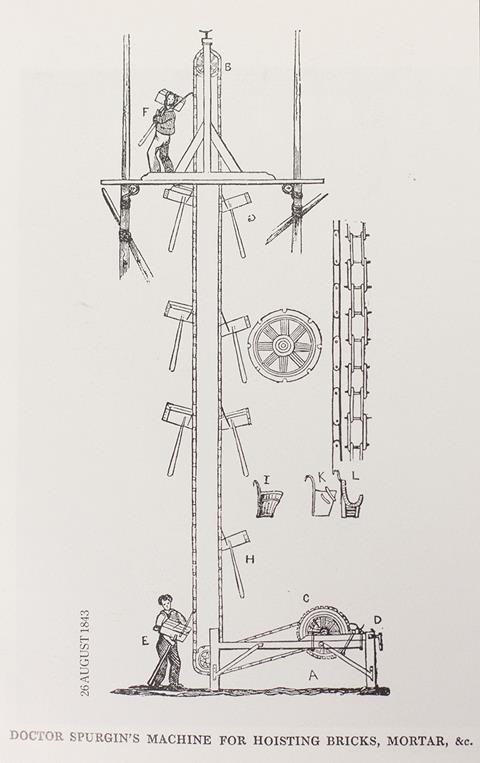

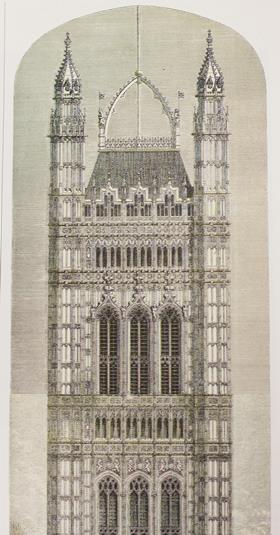

Here’s 10 reasons why building the superstructure ran less than smoothly. We’ve also found an extract from Building magazine in 1850 that captures the feeling about it at the time, and some pictures from our archive of the building taking shape over the ages.

1. A controversial design

The decision was made to rebuild the Houses of Parliament following a fire in the original Palace of Westminster in 1834. A total of 97 architects entered the design competition, with Charles Barry emerging as the winner. However, Barry’s victory was tainted with rumours of deception and favouritism, and he was forced to redesign some elements of the scheme after criticism by a Commons select committee. There were then suggestions that ‘the revised designs contained some hints from the plans of Barry’s competitors”. Furthermore, his design was attacked for not fitting the brief as it was alleged that Perpendicular tracery stopped it being Gothic.

2. Cost overruns

The original estimate for the works was £707,104. However, this omitted to include £44,000 for the embankment works; £70,000 for land acquisition; £3,000 for carriageway; furnishing; fittings; heating; lighting; ventilation and the great clock. After overruns, redesigns and a host of other problems, the final figure ended up at £2.4m.

3. Delays

Barry estimated that the palace would take six or seven years to complete. It turned out being closer to 32.

4. Materials

After a tour of the country to find the most suitable stone, Barry selected Bolsover, which the job was priced on. But the supply dried up and only the river wall and some lower parts of the superstructure were built using it. It was substituted for Anston stone, which was decaying within a decade.

5. Heating & ventilating

Dr David Reid was appointed in 1840 to oversee the heating and ventilation system of the new Houses of Parliament and he was immediately at odds with architect Barry. His proposals for drawing in fresh air to the buildings meant a radical review of the design, which added £20,000 for a 300ft Centre Tower and an extra £20,680 for fireproofing. Another £12,230 was estimated as the cost for adding fresh-air ducts and chimney flues, plus £12,000 for Reid’s apparatus.

6. Feuds

Initial disagreement over ventilation was the start of a 12-year war between Reid and Barry. Barry argued that Reid had proposed eight different ways for ventilating the palace but was “always unwilling to commit himself to anything on paper”. An arbitrator was appointed and in 1846 it was decided that Barry should take over the heating and ventilation. However, Reid was later reappointed and there was a protracted struggle over the design and how best to ventilate the scheme between the two of them. Barry eventually took Reid to the Court of Common Pleas and claimed damages after Reid accused him of forging a document to the Commissioners of Woods.

7. Acoustics

Heating and ventilation wasn’t the only thing causing Barry a headache. The Commons had got the idea that the acoustics would be the same throughout the chamber. This lead Barry to propose a central wood-panelled ceiling six feet lower than the original with the outer sections sloping towards the windows. This blocked out part of the windows so that the sills had to be cut down by about one foot to let in more light. The cost of these alterations added £9,400 to the bill.

8. Sewerage

Consulting engineer Henry Austin found further fault with Barry’s plans by reckoning that the smell of sewage would find its way into the place. Nonsense said Barry. But Reid pitched in and stressed that he had gone to great pains to design a ventilation system that relied on drawing in fresh air and this would be ruined by the proximity of the sewer system. The sewer was moved.

9. Workforce

Progress on the project was halted in 1841 when the masons went on strike over a problem with contractor Grissell and Peto’s foreman. They stayed away for 20 months and only resumed work in 1843. Then in 1845 there was a complaint in The Spectator that craftsmen recommended by the Royal Commissioners on the Fine Arts were not being employed. It stated: “Certain it is that the most skilful and experienced practical workmen among the carvers and painters thus recommended have not been engaged.”

10. Publicity

The trials and tribulations of the project did not go unnoticed by the public. The scheme even got a mention in a play, Frankenstein, at the Adelphi Theatre:

Long in getting through with

Like certain Houses Barry has to do with.

In 1850, a question was asked in the House of Lords about when the new building would be ready for occupation. The members dissolved into mocking laughter, a reponse that prompted Building magazine – in those days The Builder – to go and see for itself.

Building ran this report in February 1850:

“We walked from one end of the enormous building to the other a few days ago, and were grieved by the air of desolation which everywhere prevailed.

Few workmen were to be seen except in one or two quarters; and these moved with that listlessness which follows want of energy in the direction. To a very large portion of the building nothing whatever has been done for four years - there it stands in carcass just as it did four years ago! The first contract, commenced ten years since, and which was to have been completed in three years, is positively not yet wound up.

“Our readers who understand these things will laugh when we tell them that the whole number of joiners now employed on the building is thirty - four flies to eat up an elephant. They perhaps may get through the job if they live long enough, but it will be a weary while first.

“Members who produced the ‘tittering’ and ‘much laughter’ on Monday night and shrugged their shoulders to express their belief that under the present direction they never would get into their new quarters, surely cannot know the realy facts of the case. They cannot be aware that the fault is their own, and solely their own.

“Looked at every way, the results of the course which has been pursued are seen to be bad, and we would very seriously urge on the attention of Government, the importance of doing different in future and proceeding vigorously with this great work: employment is wanted, loss is caused by delay -nothing can be gained by it; enormous rents are being paid which might be saved, and the dignity of the country is in a degree compromised.”

No comments yet