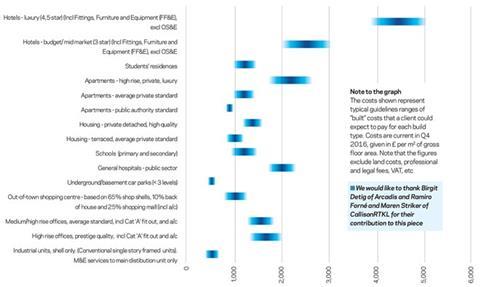

Ciara Walker, Birgit Detig and Ramiro Forné of Arcadis and CallisonRTKL consider whether Berlin will still be sexy, when it is no longer so poor

01 / Introduction

Berlin has for a long time relied on its image of counterculture, creativity and cheapness to draw innovative start-ups and entrepreneurial people to it, as well as the fact that it is Germany’s cultural centre and seat of government. Now that this tactic has truly paid off, and the beginnings of an economic and real estate boom are visible in the city, the question arises of how Berlin can keep the essential qualities that make it unique while it modernises and gentrifies, consequently becoming more expensive, drawing fewer creatives and start-ups.

A polycentric city known for its diversity of neighbourhoods, Berlin will need to invest in its communities and provide housing across income levels to keep its character while growing into its full potential as a capital city.

02 / Economic and political overview

Economics

From a debtor state recuperating from its Cold War division and reunification, Berlin has finally turned around its economy, growing at 3% in 2016, above the 1.9% average for Germany and consistently outperforming national growth over the past three years.

Berliners have seen unemployment fall from 19% in 2005 to 9.5% in 2016, and much needed growth in real wages. This was accompanied by buoyant urban construction, surging tourism and unprecedented interest in real estate between 2010 and 2015. The city was described in the 1990s as “poor but sexy”, and still needs many years of growing faster than the rest of Germany to catch up.

Berlin is unusual in Germany for having a focus on services over industry. The city is renowned for science and research, with 170,000 students and researchers at four internationally renowned universities, 41 higher education institutions and 67 research centres. Now, with Germany’s Industrie 4.0 policy of investment in the future of industry, Berlin is leveraging these resources to re-industrialise, focusing on high tech and clean tech.

The city’s population is expanding rapidly, with 40,000 added a year as well as the refugees welcomed in 2015 and 2016. This has contributed to economic growth, filling new jobs as they are created, and creating demand for additional goods and services. However, the population growth also presents challenges, requiring additional housing, social infrastructure, infrastructure improvements and even commercial space to accommodate the new jobs being created.

A main challenge for the city is retaining its character while accommodating this additional demand, and the rising prices which will come with booming real estate. Already 600 artist studios have disappeared in the past two years, and initiatives such as the Alliance of Berlin Studio Buildings (conversion of 38,750m2 of former government facility into a housing complex for refugees and creatives) may not be enough to keep Berlin’s counterculture and creative character intact.

Politics

Germany consists of 16 federal states, with income distributed by central government according to the solidarity principle of richer regions compensating poorer. As recently as 2012, Berlin was the biggest recipient, claiming a payment of £2.7bn, due to its East Germany economic legacy and the cost of reunification, but in the last few years it has been paying down its debt with budget surpluses each year. The Berlin Senate has 160 elected members and elects the mayor of Berlin and the eight senators responsible for running the city. The city is further subdivided into 12 boroughs, each governed by a borough council with responsibilities for planning, among other things.

The elections in September 2016 led to a change in local government: the SPD, Die Linke and Die Grünen coalition now jointly govern Berlin. The government is beginning to outline the path forward, and the markets eagerly await the direction taken on important decisions such as whether to allow high rises, or build into Berlin’s green spaces, both unpopular options. They will follow the framework laid out in the Berlin Strategy 2030, which provided an inter-agency framework for long-term sustainable development of the city for the first time since reunification in the 1990s, led by Berlin’s Urban Development Department.

Table 1: City indicators

| City-region indicators (2016) | Berlin | Greater London |

|---|---|---|

| Arcadis Sustainable Cities Index 2016 | 25th | 5th |

| GVA (£) | 89.7bn (2014) | 378.4bn (2015) |

| GVA per head (£) | 26,778 (2013) | 43,629 (2015) |

| Year-on-year economic growth (%) (2015) | 2.20% | 3.20% |

| Unemployment rate (%) (2016) | 9.20% | 6.10% |

| Population (2016) | 3.8m | 8.7m |

| Population growth rate (annual %) (2016) | 1.30% | 5.70% |

| Population density (people per km2, 2016) | 4,049 | 5,518 |

| Overnight stays (2014) | 28.7m | 28.8m |

| CO2 emissions (2011) | 19.8m tonnes | NA |

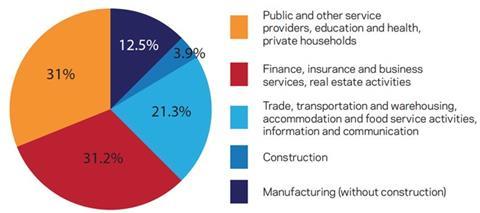

Diagram 1: Gross value added in Berlin 2014

03 / Innovation

The Berlin Strategy mentioned in section 2 acknowledges and highlights the importance of innovation and technology to the Berlin economy. It has identified five innovation clusters to be developed:

- Energy management

- Healthcare industry

- IT, communication, media and creative industries

- Optics

- Transport, mobility and logistics.

Every third company in Berlin is active in one of these clusters, together generating over £87.6bn in revenue, almost 40% of the capital’s turnover. The city is recognised as one of the prime locations for science in Germany, and is among the top three innovation areas in the EU. Some 3% of the workforce work in R&D, and 4.2% of GDP is spent on it, more than any other German state. The Berlin Strategy aims to strengthen this position with investment in facilitating innovation, through improved networks of learning institutions and research centres, development of multiple innovation hubs, safeguarding and developing industrial and commercial space and promoting start-ups with improved access to services, contacts, capital and space. Science parks such as Adlershof and Buch alongside the research-intensive universities are the cornerstones of the Senate’s ambition to turn Berlin into an innovative state with significant knowledge-intensive industries and jobs.

The start-up and technology ecosystem in Berlin has played a big part in driving the transformation of Berlin’s economy, with a start-up said to be founded in Berlin every 20 hours and an ecosystem of more than 2,000 start-ups and 60,000 employees. Tech royalty such as Twitter, SoundCloud and Uber have set up shop in “The Factory” (a 16,000m2 campus hosting start-ups in a former brewery), and this type of repurposed, multifunctional space is increasingly being adopted in the city. Berlin competed with London for the title of top start-up city in Europe over the past three years, and an essential advantage for Berlin is the low cost of living and creative vibe of its many, diverse neighbourhoods. Combined spending on housing and transport in the city was 20% lower than other parts of Germany in 2015.

In addition to this, Berlin also offers cheap space in abundance, through the provision of plenty of co-working spaces to facilitate collaboration and incubate ideas (more than 120 across the city). Berlin is also looking to benefit from Brexit, feeding the start-up boom and enticing the best and brightest away from London.

However, Berlin may not remain so “cheap and sexy” for start-ups for long, with increasing interest and limited supply of housing and office space at risk of creating a property market bubble. When prices get too high for the innovative start-ups feeding the city’s growth, they may look east to the growing start-up cultures of Budapest and Prague.

Some measures to combat this are already being put in place, such as plans to set up public-private space exchange, facilitating the interim use of available spaces and premises in public possession by private enterprise.

04 / Infrastructure

Berlin’s post-war population has still not reached the 4 million people living there before the Second World War. The city now has 3.8 million people and is growing rapidly, however the infrastructure, built to last for a bigger city, still has significant capacity in terms of road networks and tracks. The public infrastructure provision is high quality, with a network that spans the entire city, and a combined regional and suburban train, underground, tram and bus network covering some 1,900km and over 3,100 stops serving more than 1.4 billion passenger journeys in 2013.

Modernisations and upgrades, as well as the development of underground transport are on the agenda, but take a back seat to accommodating new residents and ensuring access to the necessary social infrastructure. The Green party in the coalition is likely to push for investment in cycling and investments are planned in the Berlin Strategy for simpler multimodality, concerning both walking and cycling.

Though public transportation in Berlin is quite well provided for, there are still some challenges around private transportation including additional parking and alleviation of some congestion points. It is also worth noting that maintaining and investing in suburban transport infrastructure is essential to Berlin, with more than 154,000 commuting into the city and 67,000 Berliners commuting out every day.

In the 1990s, Berlin set out to improve its international access, and create an appropriate gateway for the capital city in the building of a new airport. However, this project has been beset with delays, cost overruns and challenges, and there are now indications that by the time the project is delivered (now delayed again to 2018) passenger demand will already surpass the increased capacity. When the new airport does open, the existing airport, Berlin Tegel, will close and be transformed into the Berlin Urban Tech Republic with a tech campus, residential and commercial areas and a focus on clean and urban tech. The area will also be a testing ground and modelling space for a future-proof sustainable city, building on Berlin’s goals of a high-tech future.

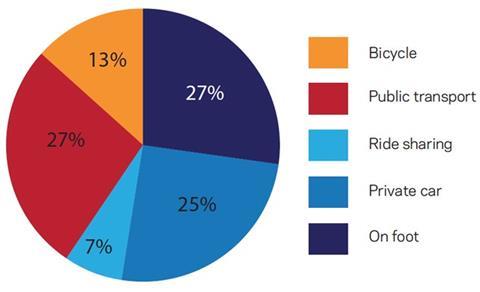

Diagram 2: How Berlin moves

05 / Social infrastructure

Schools in Berlin need investment, both due to a refurbishment backlog, which needs to be addressed, but also to accommodate the growing numbers of students. As such development sites for schools are being safeguarded, and education establishments are being rebuilt to provide accessibility and meet inclusive standards. There have been discussions around using a delivery vehicle, focusing the responsibility for school construction into one entity to speed up the buildings of schools, currently an eight-year process.

Berlin is also investing in its health facilities, both to meet the needs of the expanding population and to cater to the growing medical tourism market. The Senate is focused on developing this market, and will invest £850,000 in the becoming the number one location for medical care in Germany through the “Medizinhaupstadt Berlin” project.

06 / Residential

Berlin’s rapid growth is causing dynamic development in the residential market. Rents and prices are rising and a growing number of large-scale development projects are coming through the construction pipeline. The development scene in Berlin is very diverse, ranging from major projects by public housing corporations and private developers all the way through to privately initiated cooperative projects or prime developments in the centre for more international buyers. Berlin is unusual in Germany in that it is a rental city; 85% of all dwellings are rented flats, and there is a significant social rented sector, which could be left behind in a real estate boom.

The residential market is expanding significantly and asking rents have been growing, shooting up by 4.6% in 2016. Asking rents are rising more rapidly than other major Germany city, steadily converging to their higher price points, though rents remain 7.4% higher in Dusseldorf, 16.2% higher in Hamburg, 37.9% in Frankfurt and 67.8% higher in Munich. A similar pattern is seen in the sales market, with asking prices rising sharply across the market, to a median of £2,796 per m2, 9.6% higher than in 2015.

The Berlin Senate is aiming to almost triple the latest rate of new build completions (7,030 units in 2015) to 20,000 (half London’s target of 42,000) a year, a higher delivery rate than any of the other major German cities, and a feat for the traditionally slower moving Berlin. Construction of housing is already growing, and though there were only seven more projects in 2016 than 2015 (2.9% growth) there was 44% growth in the pipeline of apartments to 32,240 planned units, indicating that developments are growing larger.

Purchasing power is still lower in Berlin than other major cities in Germany, a full 42.5% behind the front-runner Munich. A main objective of the Berlin Strategy is to keep Berlin affordable, with housing for all income levels. As such there is an obligation on developers to include at least 30% affordable housing within any new development and citywide rent controls were introduced in June 2015 based on typical rents.

Further progress in maintaining the affordability of the city has been made through alternative housing models such as cooperatives and the Baugruppen (co-housing) resident-run building groups designed to bypass developers. Together, state-owned housing associations and housing co-operatives manage about a quarter of all Berlin houses (15% state owned, 10% co-operatives).

Table 2: Residential construction demand and activity

| City | Construction activity 2014 | Demand for construction p.a. until 2020 | Demand for construction p.a. until 2030 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Berlin | 8,744 | 19,555 | 15,785 |

| Hamburg | 6,974 | 10,424 | 9,064 |

| Munich | 6,661 | 18,408 | 11,488 |

| Frankfurt | 4,415 | 6,217 | 5,887 |

07 / Commercial

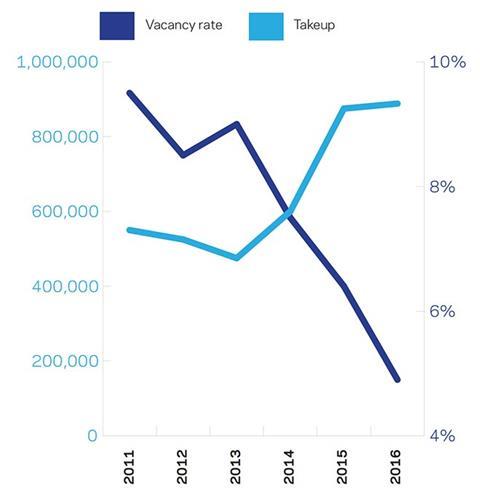

The commercial market has been expanding since 2013, reaching a new record for take-up of 888,300m2 in 2016. Berlin retained its place as the most active German office letting market, with take-up almost 100,000m2 higher than the next best, Munich. However, this high take-up also means available space to let is being squeezed, with the vacancy rate falling by more than 4.5 percentage points in the five years to 2016, to 4.9%.

In fact, vacancy of modern office space in city centre submarkets has fallen to such a low level that prospective tenants are increasingly having to compete for the most attractive space, further driving rental price growth. Prime rents have grown 17% in 2016 to £23.38 per m2 per month, and average rents have reached £13.46 per m2 per month. This was the highest rental price growth in the top five German office markets, and by some estimates prime rent could reach £25.50 per m2 per month by 2018.

Strong demand is also driving strong supply: completions rose 45% in 2016 year on year to 340,000m2 of completed office space. Although new build activity is growing dramatically, it is still not keeping pace with demand and pressure on rents looks set to continue with robust economic growth expected through 2017 and beyond.

Key completions include the new Allianz Deutschland company headquarters, which will add a new landmark building to Adlershof science park in 2019 and feature 60,000m2 of state-of-the-art office space over three buildings.

Table 3: Office space supply

| Year | 10-year average | 2015 | 2016 | 2017* | 2018* | 2019* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Office space supply (‘000 m2) | 150 | 230 | 340 | 275 | 475 | 365 |

Diagram 3: Commercial space in Berlin - CBRE

08 / Hospitality

In Europe, Berlin is ranked third behind London and Paris as a tourist destination. The city has enjoyed a record number of overnight stays over the past few years, and in 2015 set a record of 30 million, up by 7.4%. Berlin’s aim to overtake Paris for overnight stays is within sight.

In keeping with this significant growth in demand, supply of accommodation in the German capital has developed dynamically, with the number of hotel establishments growing 3.3% annually between 2006 and 2015 to 780. Beds grew by even more to 139,997 beds, or 5.3% growth per year, indicating that larger establishments are being built to meet growing demand.

RevPAR (revenue per available room) is also growing, with upscale and luxury hotels making gains of 9.5% and 8.9% respectively in 2015, and the average hotel seeing gains of 7.7%.

The pipeline of hotel development to 2020 is significant, with at least 4,500 rooms being added over more than 12 developments.

Table 4: Pipeline of hotel developments to 2020

| Project | Operator | Location | Stars | Rooms | Opening |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hampton by Hilton Berlin Alexanderplatz | Primestar Hospitality | Otto-Braun-Strasse | 3 | 344 | Spring 2017 |

| Indigo Berlin East Side Gallery | Tristar Hotel GmbH | Mercedes Platz / Mühlenstrasse | 4 | 119 | Autumn 2017 |

| Motel One Alexanderplatz | Motel One | Grunerstrasse | 2 | 708 | Autumn 2017 |

| Steigenberger Airport Hotel | Steigenberger | Willy-Brandt-Platz | 4 | 322 | Autumn 2017 |

| Toyoko Inn | Toyoko Inn | Alexanderplatz | 3 | 500 | 2018 |

| Estrel Hotel Berlin (Expansion) | Private | Sonnenallee | 4 | 814 | Late 2020 |

09 / Conclusion

In many ways, Berlin is at a crossroads in its history, with the weight of the future leaning on the decisions it makes today. Invest in real estate, at the risk of gentrification. Invest in modern architecture and creative design, at the risk of losing the unique identities of the neighbourhoods. And invest in a technological future, at the risk of losing its creative past.

How can Berlin work to embrace the future, while keeping the unique identity gifted to it by its past?

This contrast and balancing act is what makes the city so exciting, and will continue to attract people to Berlin for many years to come for start-ups, tourism, real estate investment and creative discovery.

No comments yet