The facade of 1-4 Marble Arch was retained because of its sensitive location. But its poor condition left the project team wondering whether it would in fact have been less carbon intensive to knock it down and start again. Thomas Lane reports

To demolish, or not demolish? That is the question currently exercising many within the construction industry. And this is a dilemma perhaps best exemplified by the row over Marks & Spencer’s flagship store on Oxford Street.

Should this disparate collection of buildings be refurbished rather than demolished in order to save carbon? A public inquiry considering this question – the first to do so – closed last month with a decision on the store’s fate expected imminently. Part of the argument hinges on the fact that the loss of the landmark, art deco building could potentially harm the historic character of Oxford Street.

Just 350m away, a building with a facade dating from the same period as M&S has just been completed. The building is all new apart from the 1920s facade, which has been retained for aesthetic reasons and because intuitively this seemed like the less carbon-intensive option. But now the building is finished, the project team are asking themselves whether – in terms of the carbon impacts and with the benefit of hindsight – retaining the facade was actually worth it.

1-4 Marble Arch is across the road from the famous Nash-designed triumphal arch of the same name. Occupying a corner plot, the nine-storey building is typical of the area, with a Classical stone facade incorporating a cornice at high level, sections of bay windows, decorative columns with carved pilasters and an area of brick on the east side.

There was never any doubt that this building had to retain its height, massing, and presentation

Simon Loomes, The Portman Estate

Built as upmarket apartments and turned into offices in the 1970s, the building was compromised by old services and a poor quality structure. “The building had very low floor to ceiling heights, it was peppered with columns, and it wasn’t well built, so maintaining those sorts of frame structures is questionable. And it was really at the end of its useful life,” explains Simon Loomes, the strategic projects director at the Portman Estate.

An all-new building was not seriously considered as an option because of the sensitive location. “There was never any doubt that this building had to retain its height, massing and presentation as a twinned building with the Cumberland Hotel across the entrance of Great Cumberland Place and framing the view of Marble Arch from the south,” says Loomes.

He adds that it was highly unlikely that Westminster council would have allowed demolition of the facade when the refurbishment was being discussed back in 2013 as embodied carbon was rarely considered at that time.

The proposal that initially received planning permission retained 40% of the original structure as Portman Estates and AKTII did not think demolishing the whole thing was necessary. But a thorough assessment convinced them otherwise. Retaining 40% of the structure made the job more complicated and the building would still be left with compromised floor to ceiling heights and structural grid.

>> Click here for more about the Building the Future Commission

“Once we had gone through a rigorous engineering assessment and considered the geometrical aspects, we thought a new structure was the right option for this building,” Rob Partridge, design director at AKTII, explains. The new structure is a steel frame with composite steel and concrete floors and adds an extra storey to the building.

Unfortunately, there was no opportunity to assess the facade in the same way as the building was occupied until shortly before work started. The facade comprises a steel frame embedded in a masonry and brick wall.

Partridge says this form of construction makes inspection difficult because the structure is buried inside the masonry, which necessitates demolishing some of the masonry to get access to the steel frame. This was not an option in an occupied building, and in the case of 1-4 Marble Arch was only possible once demolition had started.

A heavy steel temporary structure was needed to support the facade while the work was being done. The original plan was to use mini-piled foundations for the temporary works but the team had to switch to a mass concrete kentledge foundation system because there were too many obstructions in the ground for mini piles. This change delayed the project.

“We had several months where we couldn’t progress the project in the way we wanted to, which was all down to the facade retention system,” says Michael Jones, the Portman Estate project director. “Until the facade retention system was in place you couldn’t complete the demolition programme.” He reckons this added 14 to 16 weeks to the programme.

Above ground, AKTII discovered that the facade was in poor condition. The steelwork was badly corroded, particularly above grand cornice level. Designed in the make-do-and-mend days after the First World War, every element of the facade was unique.

For example, the cantilevered stone blocks above grand cornice level had to be tied back to the new frame with bespoke brackets and resin-anchored rods as every single block was different.

At level one a deep transfer beam was found hidden behind the masonry. This was blocking the top of the planned, large glazing to new ground-level retail units.

The answer was to install a new, shallower beam to strengthen the top of the existing beam so that the lower half could be cut out. “That was months of work,” says Jade Purdy, structural engineer at AKTII.

Every time I said we need to open up another hole everyone said we would have been better off taking it down and starting again

Jade Purdy, AKTII

There was also a column in the way of the windows. The load on this column had to be transferred to the temporary works while the column was removed, and a stronger beam installed above to span the new opening. With this new beam in place, the loads could be transferred back onto the facade via a series of jacks.

The number of interventions prompted the team to start questioning the decision to keep the old facade. “Every time I said we needed to open up another hole, everyone said we would have been better off taking it down and starting again,” Purdy says. “It would have been more straightforward.”

It would be easy to dismiss this as the grumbles of a frustrated project team, but AKTII is an engineer with a strong reputation for reusing structures where possible to save carbon. It pioneered the addition of extra floors to 1960s buildings to add value and save carbon with Southbank Tower in 2016, and took this to even greater heights more recently with Hylo in the City.

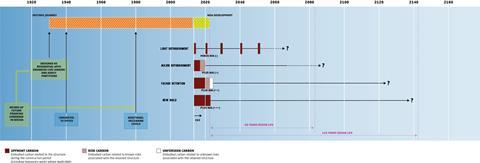

There is an assumption that retention is always better than replacement, but Partridge and Purdy are convinced that retaining this facade has been more carbon intensive than building it from the ground up. They say they have yet to crunch the numbers but are confident in their assessment of the carbon costs.

“This is based on our inherent knowledge in terms of the amount of time, effort and material that went into making this work,” Partridge says.

For starters, the mass concrete foundations needed to support the temporary works came with a heavy carbon penalty. These were broken out and taken away after the temporary works had been removed, further adding to the carbon debt.

And the multiple interventions needed to restore the facade and strengthening of elements so other parts of the facade could be removed to meet the brief for the building came with a carbon cost too. Digging out the basement and constructing the new frame is more involved – and carbon intensive - when there is a delicate facade hindering access to the site.

Partridge points out that the additional time needed to design the revised foundations for the temporary works, the facade strengthening elements and the prolonged time on site come with a carbon cost too.

And after all that time, effort and carbon the building still has a 100-year-old facade with all the compromises that entails. Partridge says it is likely that the old facade will need more maintenance, which comes with an embodied carbon impact.

“If you start with a material on the outside of the building that is already 100 years old, you are probably going to spend more money maintaining that over the next 100 years than if it was brand new,” he says.

Loomes and Jones say the old facade could have been demolished and a facsimile built using Portland stone and stock bricks as these materials and the skills needed to assemble these are readily available. They would have panelised the facade to make it easier to erect on a very constrained site.

“Once you have cleaned up and repaired the facade, the difference between that and a brand new facade is fairly minimal,” says Loomes. A new facade, in addition to offering an embodied carbon advantage, would also offer better operational performance and would last longer too.

The next step is to establish the actual carbon impacts of facade retention to inform future decision making. Partridge and Purdy would like to work out the carbon cost of retaining the facade at 1-4 Marble Arch.

Partridge adds that data will be needed from other facade retention schemes to build up an accurate picture of the carbon impacts and asks that sustainability consultants working on other schemes start collecting this data.

He reckons the bespoke nature of so many elements on the facade at 1-4 Marble Arch, which made the job so challenging, are more likely to be typical than exceptional. “We have worked on lots of buildings from the twenties and the thirties and you get far more variability in the interwar years than you do in the sixties and the seventies,” he says.

Partridge reckons this was down to material shortages combined with a less formal design process where contractors made do with what was available compared to the 1960s and later.

Project team

Client Portman Estate

Architect AHMM

Structural engineer AKTII

M&E engineer Foreman Roberts

Cost consultant Gardiner & Theobald

Project manager Buro Four

Contractor Galliford Try

Purdy says that engineers must have early access to buildings to assess the condition of a facade so they can establish the extent of remediation works. This can be benchmarked against the facade retention carbon impacts database and an informed decision made.

In some cases, this may include accepting a carbon penalty to retain a facade for its historical or aesthetic significance. Jones says the Portman Estate would look at replacing the facades of buildings in its portfolio. constructed after the first world war when these came up for redevelopment where there were carbon advantages but would continue to retain the facades of its more historically significant, older buildings which date back to the 1760s.

Either way, the Marks & Spencer’s case shows how embodied carbon is becoming a planning issue, which means that project teams will need solid data to make a case for demolition. Only then can we satisfactorily answer the question of whether to demolish and rebuild or to refurbish.

Commissioner view: Clara Bagenal George on the need for accurate carbon data

There is a lot of debate around retrofit versus demolish and many factors need to be considered, including cultural and historical significance, design quality and of course cost. But for me it all boils down to energy and carbon – retrofit should be the starting point for projects as it is likely to be the most sustainable option.

What we then need more of is accurate, consistent methodologies and data to understand the whole-life carbon impact of a development. This will help guide conversations and allow us to deliver evidence-based decisions early on in the design.

Better collaboration across the industry is important to getting the right information and tools in place to prove what is the most carbon-effective option. LETI, working with CIBSE, has created a methodology for measuring the embodied carbon impact of MEP products, which can make up a substantial part of a refurbishment or retrofit project’s embodied carbon. We have got to share this knowledge across the sector.

It is vital that assessments take a whole-life carbon approach so considering both embodied and operational carbon for retrofit and rebuild options, otherwise you are only getting half the picture. Something I think we also need to increasingly ask ourselves is whether a building design allows for flexibility and different uses later down the line.

People’s behaviours and what we want from our built environment are changing all the time, so what works for today’s market won’t necessarily be right in 20 or 30 years. Regulation on things like energy efficiency is evolving too. There is a risk that, in a decade or two, a building will have to be retrofitted again or demolished without that long-term perspective, negating any carbon savings that might have been made during a previous refurbishment.

It is about engineers and architects giving advice based on technically robust analysis so that we can be confident that we are making the best choice from a sustainability perspective over a building’s lifetime.

Clara Bagenal George is an associate at Introba and a Building the Future commissioner

Commissioner view: Simon Wyatt on why retention should always be the priority

This is a very complex issue that is being spun in both ways at the moment, with some people being very positive about retention and others who are heavily in favour of new-build. The priority should always be about carbon avoidance now, not in the future. Whole-life carbon is important, but a lot of the benefits occur in the future, whereas the climate emergency is now – so we should be focused on what we are doing here and now.

There might be instances where the embodied carbon of a retained facade is similar to new-build, but it is important to consider the relationship between the facade and structure. The sub and superstructure are generally 50% of the embodied carbon of a building but what we have seen are some developers saying that, because the facade cannot be retained, they need to demolish the whole thing. The priority should always be to retain the structure.

I have some doubts about the claim [that demolishing the facade at Marble Arch Place is better in terms of upfront carbon than demolition.] There will be instances where that is true, but those will be rare because the facade needs to be knocked down and the materials disposed of then replaced. If you retain those materials onsite, then you are saving on materials and demolition, so you would struggle to get the embodied carbon argument to stack up.

And even if the embodied carbon numbers between retention and new-build are close, we need to think about material efficiency and the circular economy. As we drive carbon down over the next decade, then material efficiency is going to become as equally as important, if not more so.

The default position should always be retain where possible.

Simon Wyatt is the sustainability partner at Cundall and a Building the Future commissioner

Building the Future Commission

The Building the Future Commission is a year-long project, launched to mark Building’s 180th anniversary, to assess potential solutions and radical new ways of thinking to improve the built environment.

The major project’s work will be guided by a panel of 19 major figures who have signed up to help guide the commission’s work culminatuing culminate in a report published at the end of the year.

The final line-up of commissioners includes figures from the world of contracting, housing development, architecture, policy-making, skills, design, place-making, infrastructure, consultancy and legal.

The commissioners include Lord Kerslake, former head of the civil service, Katy Dowding, executive vice president at Skanska, Richard Steer, chair of Gleeds, Lara Oyedele, president of the Chartered Institute of Housing, Mark Wild, former boss of Crossrail and chief executive of SGN and Simon Tolson, senior partner at Fenwick Elliott. See the full list here.

The project is looking at proposals for change in eight areas:

- Skills and education

- Energy and net zero

- Housing and planning

- Infrastructure

- Building safety

- Project delivery and digital

- Workplace culture and leadership

- Creating communities

>> Editor’s view: And now for something completely positive - our Building the Future Commission

>> Click here for more about the project and the commissioners

Building the Future will also undertake a countrywide tour of roundtable discussions with experts around the regions as part of a consultation programme in partnership with the regional arms of industry body Constructing Excellence. It will also set up a young person’s advisory panel.

We will also be setting up an ideas hub and we want to hear your views.

>> Email buildingfuturecommission@building.co.uk to get in touch

No comments yet