Scotland’s architectural pedigree goes back well before the 1707 Act of Union, and whatever the result of the referendum, its architects will continue to transform the built environment well beyond the bonnie braes of their homeland

In exactly three weeks’ time Scotland could be an independent country and a 307-year-old political pact that has turned out to be one of history’s most successful constitutional unions could be over. On one level, you could argue that the result of the imminent Scottish independence referendum will have absolutely no bearing on architecture. After all, Scottish and English architects worked together in both ends of the British Isles well before the 1707 Act of Union, a situation that the (notional) electrification of Hadrian’s Wall is unlikely to change.

But if you consider the prospect of an independent Scotland through the historical lens of what British architecture has accomplished in the three centuries since the union, then Scottish independence has the potential to be a seismic architectural event.

Demographics dictate that England has been responsible for the bulk of British architectural output and achievement since the creation of the United Kingdom, but it is impossible to overstate the huge contribution that Scottish architects and construction inventions have made to our shared architectural heritage. From Georgian architecture to the Industrial Revolution, Scotland has been at the centre of many of the historic milestones that have shaped not just our own built environment but that of buildings, towns and cities across the world.

The referendum therefore provides an opportunity to untangle the sinews of success and discern what exactly Scotland has ever done for architecture. So in advance of next month’s vote, what follows is a guide to five great architectural personages or achievements that have emanated from the c confines of this sceptred isle.

Political architecture

Ever since Nero allegedly set Rome on fire in order to further demonise the minority Christians on whom the conflagration was widely blamed, architecture and politics have always made uneasy bedfellows. We do not need to delve into antiquity to find further evidence of this tension: many of the failed council estates and tower blocks of the sixties and seventies are blamed on a misguided socio-political agenda that some claim deliberately sought to physically and ideologically compartmentalise the poor.

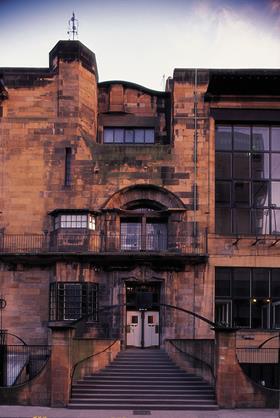

So it is understandable why recent British governments have treated architecture with extreme caution. Not so in devolved Scotland. Remarkably, in 2013 the Scottish government produced an architecture policy, a first in Britain (the Scottish Crime Campus, pictured, which was designed by BMJ Architects and Ryder Architecture was presented as one of the first built products of this new architecture policy). Despite the Farrell Review of architecture and the built environment, the UK government is a long way from offering an equivalent.

Admittedly the detail of Scotland’s policy is not entirely different to the idealistic proclamations once issued by Cabe. But the crucial difference is that Scotland has clearly identified an enforceable policy position with regard to architecture, whereas Cabe provided well-meaning but ultimately disposable advice.

Is political architectural interference (or assistance) a good thing anyway? Cabe made as many enemies as it did friends. According to Sandy Robinson, principal architect at the Scottish government: “We’re not here to tell architects what or how to design, but to maintain a framework that ensures that people and places are at the heart of architecture.”

Will it work? Like the prospect of Scottish independence, only time will tell.

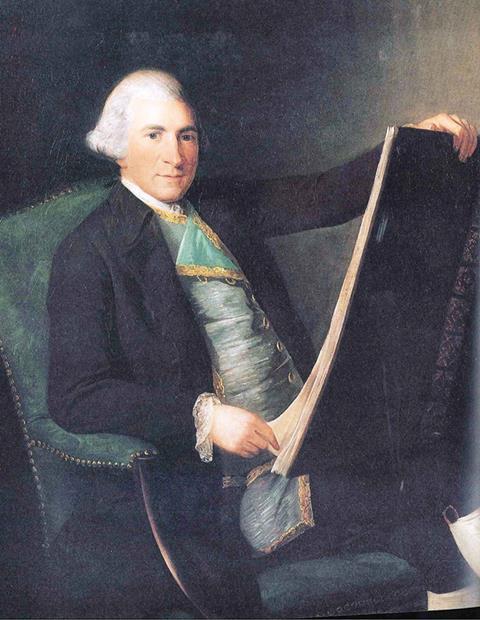

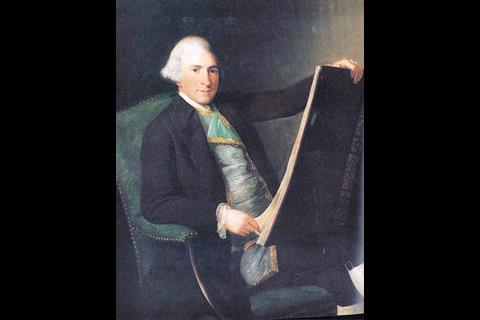

Robert Adam

Robert Adam was one of the giants of 18th-century British architecture and his influence was felt not just across the UK but from as far afield as Russia and North America. He was influential in establishing the neo-classical revival that replaced Palladianism and dominated British architecture from the mid-18th century until well into the Victorian era. Adam is also one of the few British architects to have received the cultural accolade of having a style named after him.

A key player in the Scottish Enlightenment, Adam, like scores of his countrymen before and after him, headed south to London to make his fame and fortune. There his practice produced some of the defining buildings of his age and his obsession with the totality of design, right down to curtains and furniture, ensured that his brand of precise and delicately detailed classicism also became one of the earliest recognisable styles of interior design in its own right. In England, where most of Adam’s work was commissioned, he designed scores of country houses (including Hampstead’s Kenwood House, pictured) and was responsible for several speculative residential and town planning ventures in London, including Portland Place and Fitzroy Square. Arguably the most significant of these, the 1775 Adelphi on the Strand, has been largely demolished but it set a significant precedent for the fledgling role of the architect/developer.

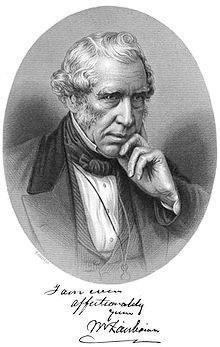

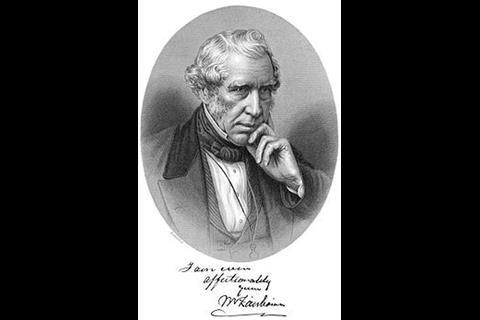

Tubular steel

Next time you mourn another England football defeat under Wembley’s famous arch or stare up at the roof of the new King’s Cross concourse, bear in mind that you have a pioneering Scottish engineer to thank. Sir William Fairburn is part of long line of 19th century engineers responsible for industrial breakthroughs that still shape modern Britain today. John Rennie built London Bridge (the “New” one sold to the Americans in 1968, not the motorway flyover of today) while Thomas Telford helped establish the national canal networks that became the industrial arteries of Victorian Britain. No such Anglo-Caledonian civic rapprochement for Fairburn but his invention was arguably even more significant.

Fairburn was a bridge and ship designer and discovered that by treating both as essentially metal tubes, it was possible to create a lightweight structure that retained incredible strength and stiffness.

Fairburn primarily worked with wrought iron but his innovations heavily informed the development of cold-formed steel where steel sheets are rolled or pressed to form construction components such as beams, columns or joists. The technology proved particularly popular in the US in the late 19th century but has since gone on to be adopted as a common construction procedure across the world.

James I

While James I ruled as James VI of Scotland before the unification of the English and Scottish crowns in 1603, his Welsh, English and French ancestry suggests that nationality is only ever a measure of how far back in time you care to look, a fact that all nationalists, including the SNP, find uncomfortable. Nonetheless, regardless of his genealogy, the urbane, philosopher son of Mary Queen of Scots (half-French) changed the course of British cultural and architectural history forever.

In 1616 he commissioned architect Inigo Jones to design a small palace for his Danish queen beside Henry VIII’s then Tudor Greenwich Palace. The Queen’s House was the first classical building ever built in Britain. It is hard to overstate the impact this elegant pavilion had on British culture. Without it we would not have had Georgian terraces or the Palladian country house. With its whitewashed walls, level roofline and orthogonal profile, the Queen’s House might as well have been an extraterrestrial visitation to a populace more familiar with the florid, mannerist irregularity of the Elizabethan and Jacobean styles. By giving the royal seal of approval to this radical European style, James I helped drag England kicking and screaming into the classical age and ultimately the modern world.

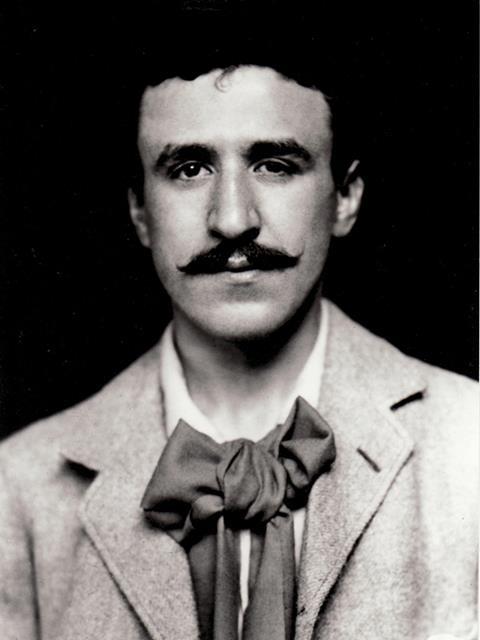

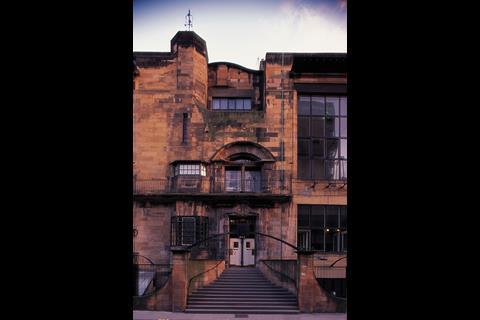

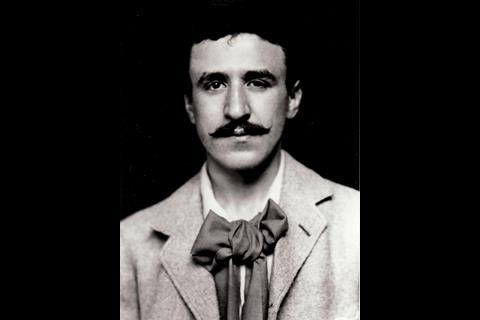

Charles Rennie Mackintosh

Charles Rennie Mackintosh is part of a rich lineage of Scottish architects who have had a significant impact on British architecture. Before Robert Adam there was Colen Campbell who set the tenets for Georgian architecture in his groundbreaking book Vitruvius Britannicus, and the buildings of his great rival James Gibbs, designer of Trafalgar Square’s seminal St Martin-in-the-Field’s church, skilfully handled the potentially fractious transition between the baroque and Palladian eras.

Mackintosh was perhaps Britain’s leading exponent of art nouveau and he was uniquely effective in mixing the innate naturalism of the style with the vernacular sympathies of Lutyens and technical foresight of Frank Lloyd Wright. But as with all great artists, Mackintosh’s style was an incontrovertibly personal and enigmatic one. A resolute modernist, his genius was to infuse the sometimes utilitarian rigour of modernism with eloquently conceived flourishes of artistry and ornamentation. Like Adam, he ingeniously evolved this into a signature interior design style that was deployed not just on buildings but on virtually everything from lamps and handrails to doorknobs and chairs. Much of Mackintosh’s fame came after his death, but his work is now internationally recognised as so valuable an artistic commodity that his style transcends European, British or even Scottish architectural classification.

Which architects or projects would you include in Scotland’s architectural hall of fame? Post your views below

1 Readers' comment