The £1.7bn Westfield London, Europe’s biggest in-town shopping centre, finally opened last week. But is it the shining example of urban regeneration that its developer claims? Martin Spring fought through the crowds to find out

When Tory environment secretary John Gummer instigated a widely supported ban on new out-of-town shopping centres in 1993, he intended to prompt the regeneration of Britain’s high streets. Nobody predicted that out-of-town shopping centres would, instead, turn the tables and invade our city centres.

This is exactly what has happened in Shepherd’s Bush, west London, where Australian developer Westfield has just opened a gargantuan £1.7bn shopping centre that contains 280 shops and 47 restaurants, bars and food stands, far more than you find in most town centres. These are spread over a floor area of 150,000m2, which makes Westfield London Europe’s largest in-town shopping centre. In the UK it is eclipsed in size only by the MetroCentre outside Gateshead and Bluewater in north Kent.

Westfield London is billed as a glittering example of urban regeneration, but is it really? Well, the 17ha site was brownfield land formerly occupied by defunct industrial buildings. And yes, the development has entailed investing some £170m in urban

infrastructure, including one new and one remodelled tube station, an overground railway station, two bus stations and 570 cycle parking spaces. And where the development meets the nearest residential area along its western flank, its perimeter wall does not overwhelm the row of Victorian terrace houses opposite.

The £1.7bn centre contains 280 shops and 47 restaurants, bars and food stands – far more than most town centres

But along the southern flank a free-standing blank wall blocks off all views in or out. Alongside runs an alleyway onto which spill several restaurants, cafes and bars, but these are likewise cut off from the local area. By being so insular and inward-looking, the complex shows its true colours as an out-of-town centre.

As for the complex itself, the 300-plus retail units have been consolidated into one enormous L-shape. Nearly all shops open on to wide double-decker internal malls, with a four-storey atrium at the centre. The sheer scale is disorientating. A few minutes’ shopping are enough to make anyone lose their bearings, and the signs at every corner are obstinately unhelpful.

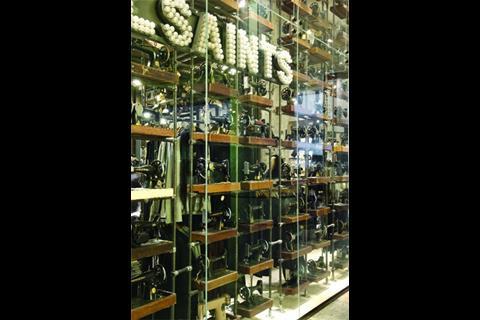

Unlike Bluewater, designed by Eric Kuhne, there’s no overall architectural theme that shines through. This may be because the original consultant Benoy, which gained planning permission, was eventually replaced by Westfield’s in-house design team. Instead, the malls are wide and lofty enough to let individual shop fronts blaze forth in a frenzy of competing lights, colours, gimmicks and logos. A retail zoo alright, but when animated by throngs of punters weaving in and out, an exhilarating one.

In one or two places, the complex does manage to rise into passable architectural set pieces. In the open-plan food court lining the central atrium, several compact restaurants flow into each other, with bar counters lining open kitchens and sparkle added by an array of recessed spotlights. Another high point of the complex is the so-called Village, which brings together 34 exclusive brands such as Louis Vuitton, Prada and Joseph. Suitably sumptuous and glitzy, this is a sinuous arrangement of clear-glazed shop fronts. Its dramatic centrepiece is a curving champagne bar overlooked by a sweeping glass staircase.

Unlike Eric Kuhne’s Bluewater, there’s no overall architectural theme that shines through

Westfield London may have opened at a time when consumers are tightening their purse strings, but the fact that 160,000 punters flocked to the opening last Thursday appears to indicate it is a blazing success. “Wonderful, really beautiful and very modern”, “I’m really excited”, “Quite overwhelming” and “It’s amazing: I can’t believe it’s right on my doorstep in Shepherd’s Bush” were among shoppers’ comments.

One of these punters also mentioned the £4m pledged for a much-needed facelift to the local park.

Another indication of the scheme’s impact will be the number of existing local retailers that are put out of business and replaced by charity and second-hand shops. But that will take longer to register.

No comments yet