The Voorlinden museum in Holland wanted naturally lit gallery spaces full of light. But how to do that while protecting the superlative art collection on display? Arup came up with a highly imaginative solution. Ike Ijeh reports

Inevitably when thinking of Dutch museums, the mind is drawn to the great collections of Amsterdam housed in famous institutions such as the Rijksmuseum or Van Gogh. But a new museum in the quiet, little-known town of Wassenaar in the western Netherlands could yet give the old masters a run for their money.

Earlier this autumn the new Museum Voorlinden was opened by the equally new Dutch king in order to house the superlative private art collection of Dutch industrialist and celebrated art collector Joop van Caldenborgh. The building was designed by Dutch practice Kraaijvanger Architects in conjunction with Arup’s Holland office.

While the museum is fully open to the public and has the former Rijksmuseum head as its director, unlike Amsterdam’s national museums this one is privately owned. This, however, is not the only way in which this museum is different from more conventional institutions.

For one thing its setting is distinctly rural. Nestling in lush, richly landscaped gardens on the edge of the town, reaching Voorlinden requires at least a half an hour walk from the nearest public transport and is discreetly sheltered away from street view.

Additionally, architecturally, the building is a much more minimalist and sedate version of what one might expect of a larger, national museum. The single-storey block is soberly clad in glass and stone, and is expressed as a pavilion-like hybrid between early classical and early modernist forms and geometries. The minimalism continues inside with its 20 galleries subdivided by six parallel structural walls and arranged into a sequence of spartan, assertively functional spaces.

But it does not take long to realise where the primary source of architectural interest lies in the building: its extraordinary roof. This is first visible externally, in the broad canopy that extends out over the colonnade in which the building is wrapped.

But it is internally where the roof makes its biggest impact. Each gallery appears awash with natural light from the roof above. But the light is transfused through a perforated membrane stretched over the ceiling which bathes each space in a balmy almost ethereal glow.

The experience is the result of a highly innovative roof construction system the like of which has not previously been applied to any gallery to date. It includes an extraordinary technical composition of three layers, 115,000 angled-cut tubes, 2,800 indirect LED modules, 2,500 glass panels and a gaping 2m roof top void.

“The roof was primarily a result of the client’s eventual desire to have naturally lit gallery spaces full of daylight,” recalls Arup lighting designer and engineer Solmaz Esmailzadeh. “Obviously natural light is used in art galleries and museums but the challenge is how it can be controlled and modulated in order to best preserve the exhibits. This was particularly important because as well as the client’s private collection, the museum was designed to house items on loan from other museums too.

“So in order to develop the design, we went through many options and even created two 1:20 prototypes and a further 1:1 mock-up which we tested in both sunny and cloudy conditions. The final design is the optimisation of this high level of technical scrutiny and analysis.”

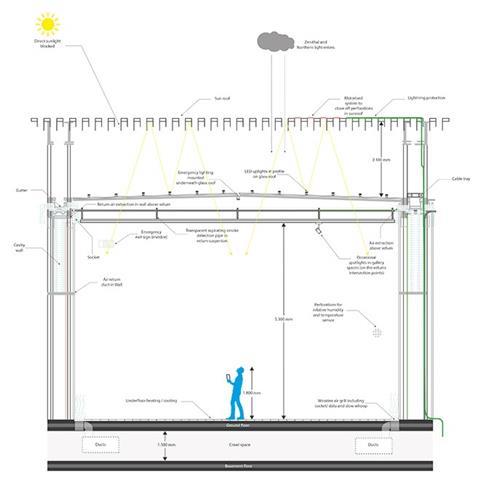

As built, the roof is divided into three levels, each one of which performs a vital function in terms of both transmitting and diffusing sunlight. In order for these effects to be realised, all the plant and services that might conventionally have been placed on the roof are located in a specially constructed basement.

The middle level of the roof structure is the glass roof, set to a very slight slope. This is supported by aluminium profiles that rest directly on the museum’s steel superstructure and it provides the main thermal separation between interior and exterior.

The glass roof has been vigorously designed to optimise daylight, insulation and colour and incorporates 65mm triple-glazed, low ion glass and has a high colour rendering index of 95%. The colour rendering index is significant because it measures the degree to which an artificial light source can mimic the colour characteristics of a genuine light source such as sunlight. It is therefore important in ensuring that when artificial light is deployed, it matches natural conditions as closely as possible.

Approximately 475mm below the glass roof sits a velum gauze ceiling. This is directly visible from the gallery spaces below. The velum gauze is stretched over the entirety of the interior and consists of two layers. The lowest provides a translucent veil that prevents viewing the roof construction above. The upper layer comprises a micro perforated acoustic sheet. Together, this velum membrane not only meets aesthetic and acoustic requirements but also provides ventilation that prevents condensation on the glass roof above. Visually, it is also chiefly responsible for the even, filtered glow evident in the gallery spaces.

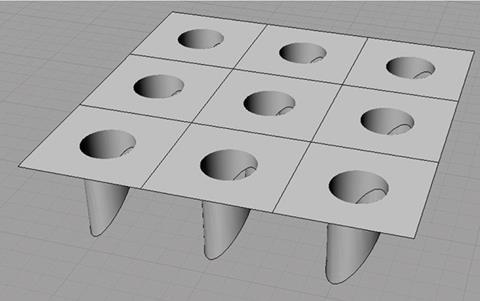

The final, uppermost layer of the roof is arguably the most significant. Esmailzadeh refers to this as the sun roof and it is the final external layer placed a hefty 2m above the glass roof. This panelled roof comprises 2,500 individual glass panels and 24% of its surface area is perforated by 115,000 glass cylinders which vary in height according to the orientation of the building and its relation to the pervading sun path. Accordingly, the lowest cylinders face north and the highest south.

The cylinders are all 125mm diameter and are cut with a 45° angle at their base. The purpose of this construction is to provide a giant universal canopy over the entire building that admits natural light but avoids direct sunlight being transmitted directly onto the glass roof below. Both the tube composition and the 45° degree cut provide the means to diffuse and divert daylight respectively. The generosity of the 2m void is primarily for maintenance reasons, although it in itself provides an additional spatial filter to further minimise the impact of direct sunlight.

The roof’s final ingredients are outside. While the velum, glass and cylinders are effective at admitting and controlling light in most daylight conditions, a temperate northern European climate means that there will often be instances when natural light is insufficient for the gallery spaces below.

To counteract this, 2,800 waterproof LED modules have been placed above the glass roof. When required, they perform an ingenious function. By facing upwards towards the sunroof, they can reflect light back down into the gallery spaces rather than directly into them and the light can still be diffused by the velum in the same way that natural light is. It is the use of LEDs that makes the glass roof’s colour-rendering index so important as this determines the plausibility of artificially simulated light.

While the discreet placement of the LED modules offers these clear technical advantages, they were initially introduced at the insistence of the client who was adamant that no light fixture should be visible throughout the entire museum. Their concealment above the glass measure also offers two further practical advantages. First, it makes the LEDs easier to access and thereby maintain. And secondly, it reduces the potential for overheating in the gallery spaces which results in a lower mechanical cooling capacity.

As with much of the most ingenious technical design solutions, virtually none of the artistry evident in this remarkable roof is visible to the public who peruse the galleries. But while the apparatus itself is not visible, what is is the extraordinary quality of light experienced below. It comes as a result of landmark roofing solution that imaginatively responds to the perennial environmental challenge of how to admit but regulate natural daylight.

Project Team

Architect Kraaijvanger Architects

Client Caldic Collection BV

Main contractor and project manager Cordeel Netherlands

Structural, services and lighting engineer Arup

No comments yet