The V&A’s £49.5m subterranean extension had to be built without closing the main museum and without damaging the listed facades of the surrounding buildings. Building reports on how Arup, AL_A and Wates made it without a wobble

The V&A’s £49.5m subterranean extension had to be built without closing the main museum and without damaging the listed facades of the surrounding buildings. Andy Pearson reports on how Arup, AL_A and Wates made it without a wobble

In May the V&A, the world’s largest museum of art and design, opened its first ever event to celebrate the role of engineering in our daily lives. Engineering Season is billed as a celebration of the vital and creative role these “unsung heroes” play in the formation of the built environment. The event includes the first major retrospective of Ove Arup, one of the most influential engineers of the 20th century.

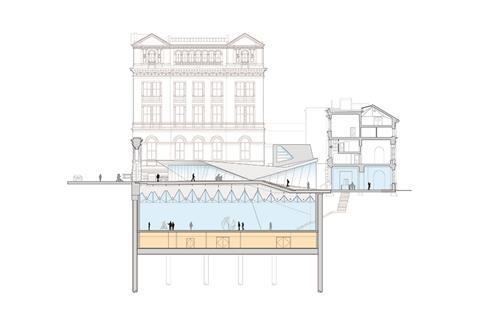

The theme and timing of the event could not be more apposite because in a small courtyard next to the V&A’s Exhibition Road entrance, work is under way to build a £49.5m underground extension to the museum. Squeezed between the Henry Cole Wing, the Aston Webb Building and the Western Range (the building linking the two main buildings) this new subterranean gallery will provide the museum with 1,100m2 of column-free exhibition space. Fittingly, the new gallery has been engineered by Arup, the consultancy founded by Ove in 1946.

Arup is working with AL_A, the architecture practice headed by Amanda Levete, after the team won the international competition to design the extension in 2011. AL_A’s design seeks to maximise space for exhibitions by exploiting every square millimetre of the courtyard. To do this the scheme had to be engineered to enable the 40m long, 30m wide, 15m deep extension to be constructed in the ground, a shovel’s length away from the listed facades of the surrounding museum buildings while, at the same time, enabling the museum to remain open to the public with all of its priceless exhibits still in place.

While the new gallery might be hidden from the street, AL_A’s scheme has turned its street-level roof into an eye-catching new public space complete with the obligatory cafe; both the courtyard and cafe will be covered in thousands of handmade ceramic tiles (see overleaf). When the extension opens in 2017, visitors will be able to pass through the courtyard from where they will step down to the new entrance lobby which is being hewn from the ground floor of the Western Range building 1.5m below road level.

On site now, construction of the gallery box and its steel truss roof is finished. Beneath the roof, the cavernous exhibition space is filled with a forest of scaffolding that supports a temporary work platform from where operatives are installing services inside the gallery’s triangular roof trusses before hiding them behind a plasterboard finish. At the same time, on top of the roof, contractor Wates is pushing ahead with construction of the courtyard and its cafe. The current focus is on construction of the cafe’s undulating roof, which rises and falls as it doglegs around the south-east corner of the Henry Cole Wing.

It has taken Wates almost two-and-a-half years of careful excavation and construction to reach this stage in the project. Having previously worked on Wates’ revamp of London’s Somerset House project, director Neil Lock says he relished the task of building the new gallery: “When this job came along, I took it because I wanted a project that would be a challenge from start to finish.” He says he’s not been disappointed.

Screen test

The project started with the painstaking removal and storage of the grade I-listed Aston Webb Screen, which separates the site (formerly known as Boilerhouse Yard), from Exhibition Road. This pillared stone wall was erected in 1909 to hide the clutter of Boilerhouse Yard from the street. On completion of the works the screen’s pillars will be reinstated, minus the sections of wall spanning between them to open up the new courtyard to the road. The pillars will be used to support new aluminium gates which will incorporate a bespoke design by AL_A to memorialise the Second World War shrapnel scars gouged into the surface of the original stone screen.

With the screen gone, Wates’ first task was demolition of the V&A’s old boilerhouse (the museum now gets its heat from the Natural History Museum’s district heating system) and the 1970s temporary buildings cluttering the yard. This task was more difficult than it might at first appear because the foundations of many of the yard buildings were joined to those of the main museum buildings. “The plant room foundations were tight against the Aston Webb building so that when you banged them, the vibrations went up through the Aston Webb building to where the artefacts are on display,” says Lock. Wates’ solution was to cut a 1m wide slot out of the foundation to isolate it from the museum before breaking it up for removal from site. If dangerously high vibration levels were detected, an alarm would trigger on the vibration monitoring system, halting demolition until a less intrusive solution could be found.

Construction of the subterranean gallery and its accompanying basement commenced with the installation of a secant piled wall. This watertight retaining wall follows the perimeter of the new gallery. It is formed from over 400 intersecting, 900mm diameter piles bored to a depth of 25m.

Boring piles into the ground less than 1m from the museum’s listed buildings meant that their facades, which includes one of the UK’s only examples of sgraffito decoration, had to be protected against oil and concrete spills from the piling operation. “We couldn’t fix protective sheeting to the buildings because that would have damaged the facade so instead we had to double-wrap all the pipes on the piling rig in case one of the hoses split,” says Lock. “Luckily none did.”

The secant piling even extends beneath the Western Range building where it encloses a new stair and entrance to the gallery. “The entrance added to the structural challenge; it meant starting the basement dig inside the existing building and then digging out, under the wall and into the new gallery,” explains Lock. Height constraints inside the building meant the large diameter piles had to be bored using a Martello piling rig - a dwarf version of the rigs used outside.

In addition to the perimeter piles 13 tension piles, measuring 1,200mm in diameter and 50m long, were driven into the ground in the centre of the courtyard. Because there is no structure above, the new gallery is effectively a concrete tank buried in the ground. The tension piles are designed to effectively nail the box down to ensure it resists ground heave. “A lot of this is very theoretical so we’re working with the University of Cambridge to monitor the installation,” says Carolina Bartram, associate director at Arup.

With the secant piled walls in place, excavation of the gallery box could commence. Up to 40 truck loads of earth were removed from site each day.

Settlement of the surrounding buildings was monitored carefully. Once the ground level had been lowered by 8m an extensive propping system was installed to support retaining walls and to stop the surrounding buildings settling into the newly formed hole. “Arup did a detailed analysis of expected settlement of the buildings while we were piling and excavating,” says Lock. He says that one of the buildings initially settled a lot quicker than predicted but that the rate of movement slowed as the works progressed.

As the ground level was lowered the tops of the tension piles were chopped back accordingly. Once the depth of the excavation had reached approximately 11m below street level, the 300mm thick gallery floor slab was cast to provide a low level restraint to the secant-pile retaining wall.

The gallery slab was cast with what Lock describes as two “mole-holes” to enable the top-down construction of the gallery basement. Excavators were placed in the openings from where they burrowed down beneath the slab and out from the openings to carve out the extension’s 4.5m deep basement. Once the void had been excavated, the basement raft slab was cast so that it was attached to the tension piles.

By the end of 2015, the bulk of the excavation work had been completed, by which time over 22,000m3 of soil had been removed from the site and installation of the roof commenced.

According to Alice Dietsch, a director at AL_A, the roof structure was designed to “resolve the 1.8m level change between Exhibition Road and the entrance, and the folded appearance of the soffit expresses the form of the engineering underneath”. The roof is formed from a series of 13 triangular trusses, known on site as “the Toblerone trusses”.

The trusses are orientated to point downwards towards the gallery floor so that from below the ceiling will appear as a series of peaks and troughs; their flat top surface supports the metal decking and poured concrete screed of the courtyard floor.

The 3m wide, 3m deep trusses measure up to 20m in length. In addition to supporting the roof and courtyard above, the trusses’ other main role is to prop the secant retaining walls at high level. As such, they span north-south between a series of fin-walls, which abut the secant piled wall adjacent to the Aston Webb building, to a giant 40m long primary truss that bisects the gallery roof in an east-west direction. The half of the roof between the primary truss and the Henry Cole wing, beneath the courtyard cafe, is supported on large I-section beams.

Ten of the 13 trusses were brought in as complete pre-assembled units on back of truck and craned into place. “It’s a tight site to get the structure into so we had to work it through with Wates,” says Arup’s Bartram.

The entrance lobby

Alongside construction of the gallery box, the other major engineering feat is the creation of new entrance lobby on the ground floor of the Western Range. To open up the 1865 building, four new openings have had to be punched through the building’s 800mm thick brick supporting walls. To construct these openings Wates used a series of steel beams, termed needles, which it threaded trough holes cored in the brickwork above the future opening. The needles are then supported at each end on temporary steelwork so that they carry the weight of the building above. With the structure supported, the openings can then be broken out so that a series of new steel beams can be slotted into place spanning the opening to carry the weight of the structure above.

The entrance to the basement, which leads from the new lobby and passes beneath the facade of the Western Range building, was constructed in similar manner. Here temporary steelwork supported the facade while sections of the pad foundations were carefully cut from the structure dragged clear of the building and broken up. A new 1.1m deep steel beam supported on steel columns was fitted to support this opening.

Having tackled so many construction challenges, it is, perhaps, no surprise that the project is behind programme. “There is a lot of unknown work with listed buildings,” says Lock. He’s coy about a precise opening date, although he can confirm it will be in 2017.

Glazing Over

The courtyard and the roof of its accompanying cafe will be clad almost entirely in 14,500 geometric porcelain tiles. The type of material is important. For tile aficionado AL_A is keen to point out this will be the first porcelain-tiled courtyard in the world.

AL_A says the choice of porcelain “responds specifically to the fabric of the museum’s Aston Webb-designed building and its collections, which include numerous striking examples of 19th century decorative ceramics”.

These are no ordinary tiles. They are bespoke to this project. They have been designed by AL_A in collaboration with Dutch ceramic manufacturer Koninklijke Tichelaar Makkum as part of a project supported by the V&A. Each handcrafted tile takes five days to make from pouring to glazing.

According to AL_A director Alice Dietsch, porcelain has never before been used for this type of high footfall application so the tiles “had to be tested for both slip and impact resistance”.

The final tile design is rhombus-shaped with a blueish-white hue in 13 different geometric patterns.

AL_A’s unique porcelain-tiled courtyard will open up the museum to allow visitors views of previously hidden facades, including those of the Aston Webb building and the intricate Italianate sgraffito decoration of the Henry Cole building.

Project Team

Client Victoria & Albert Museum

Main contractor Wates

Architect AL_A

Engineer Arup

Quantity surveyor Aecom

Lighting designer DHA Designs

Historic building adviser Giles Quarme & Associates

Planning consultant DP9

Project manager Lendlease

Porcelain courtyard and cafe roof tiles Royal Tichelaar Makkum

No comments yet