As the thrills of Rio slowly subside, attention turns to the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games, where a virtue is being made of necessity by re-using some of the venues built for the 1964 games. Ike Ijeh takes us on a tour of the new and the not so new

This weekend sees the closing ceremony of the Rio 2016 Paralympic Games and afterwards the pendulum of interest will inevitably swing to the Tokyo 2020 games in four years’ time. In one of the shortest shortlists for decades, only three final candidate cities were presented for the 2020 games with Tokyo comfortably beating Istanbul and Madrid in the 2013 vote.

This will be the second time Tokyo has hosted the Summer Olympics – the last time was in 1964. The 1964 games were historic for a number of reasons. They were the first to be telecast live internationally, they were the first ever held in Asia and they also marked the much-delayed resumption of Tokyo’s winning candidature for the 1940 games, cancelled because of World War II.

The 2020 games will also enable the Japanese capital to join London, Paris, Athens and Los Angeles as part of an elite clutch of cities that have hosted the games more than once. This is significant in terms of the construction strategy being adopted in Japan for 2020 – the Tokyo games will be the first in modern times to make such extensive use of existing venues built for a previous Olympic Games.

The re-use of Olympic venues is a virtually unprecedented event and forms a rare example of a positive, long-term legacy for Olympic venues and infrastructure. Moreover, it has also framed an organisational approach for 2020 that will see extensive use of existing venues and a relatively small number of new build projects.

Just 11 of the 37 Tokyo venues will be new build permanent buildings – the others will be either temporary or existing buildings. The venues will be spread across two main sites, the Heritage Zone and the Tokyo Bay Zone. As the name suggests, the former will follow in the footsteps of London and Rio and make extensive use of Tokyo landmarks – the road cycle race, for instance, will weave through the grounds of the city’s ancient Imperial Palace. The Heritage Zone will also include the new Olympic Stadium.

The Tokyo Bay Zone will include showpiece venues like the new aquatics centre and many of these will be located on panoramic waterside locations on the central section of Tokyo’s sprawling bay. The Olympic village, which according to current plans will be powered entirely by hydrogen, will straddle the boundary of both zones. This is part of a sustainability agenda which has seen 28 venues located within just five miles of the Olympic village in order to minimise the games’ environmental transport footprint. The Tokyo committee has also been impressed by sustainability strategies adopted at Rio such as the plans to recycle temporary venues as schools and has resolved to implement similar strategies in 2020 where possible.

Tokyo is already an advanced and well connected world city with excellent public transport links and sophisticated technological infrastructure, but as with the hosting of any Olympic Games there will still be substantial organisational challenges along the way. With a population of 13.5 million, Tokyo is the second biggest city after Beijing in which an Olympic Games has ever been held and this will naturally invite logistical complexities on a massive scale.

Additionally Tokyo suffers extreme heat and humidity in August when the games will take place. In 1964, Tokyo was allowed to reschedule the games to October in order to avoid the heat but this option has not been made possible for 2020. And the games have already been the subject of a savage cost-cutting exercise by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government which has seen a number of proposals moved or scrapped, including Zaha Hadid’s infamous designs for the Olympic Stadium.

So in anticipation of Tokyo 2020, below is a rundown of some of the key venues in which the games will be held.

NEW VENUES

Olympic Stadium

Opening and closing ceremonies, athletics, football

Tokyo’s 2020 Olympic Stadium has attracted international attention as a result of Zaha Hadid’s competition-winning design being controversially dropped last year on the grounds of cost. Moreover, at the time of her death the practice was still involved in a bitter dispute with the Tokyo organising committee which was refusing to pay fees until the architect relinquished copyright. The replacement design by Japanese architect Kengo Kuma is an altogether more traditional affair. Constructed from steel and, unusually, timber, it has been inspired by traditional Japanese temples. But even this has attracted controversy with Hadid accusing Kuma of plagiarising elements of her design (allegations refuted by Kuma) and some unimpressed locals nicknaming it “the hamburger”.

Gymnastics Centre

Gymnastics

Originally planned as a temporary venue to be dismantled after the Olympic Games, the Olympic gymnastics centre will now be retained until 2030 and converted into a convention and exhibition centre after Tokyo 2020. The change was the result of the same “legacy maximisation” exercise that famously trimmed the prospects for Hadid’s Olympic Stadium. Like the replacement Olympic Stadium, it will also be a contemporary reinterpretation of traditional Japanese design and constructed primarily from wood. The venue, designed by architect Nikken Sekkei, will be built on a 100,000m² Tokyo Bay site and will have capacity for 12,000 spectators. Construction is due to start later this autumn with completion expected by 2019.

Olympic Village

Accommodation

In one of the most ambitious Olympic construction projects ever undertaken, it is proposed that the Tokyo 2020 athletes village will be run entirely on hydrogen power. If realised, it will form the largest hydrogen powered urban experiment in the world. Fuel cells installed at hydrogen filling stations being constructed around the village’s Harumi Pier site will generate electricity and heat by capturing the energy caused by the reaction between hydrogen and oxygen in the air. As well as powering buildings, the hydrogen will also be used to run local buses. The village will house 17,000 athletes and will comprise 22 buildings ranging from 14 to 22 storeys plus two 50-storey residential towers. As with previous Olympics, after the games the complex will be converted into housing with a new school and commercial developments intending to sustain a legacy population of 10,000.

Aquatics Centre

Swimming, diving, synchronised swimming

Plans for this venue have not been finalised but, as with previous Olympic Games, it looks set to be one of the showpiece venues of the entire event. With a capacity of 20,000, it will also be the largest Olympic aquatic centre of recent years with 2,000 more seats than Rio 2016 and 2,500 more than London 2012. Also, in keeping with the two previous games, it will share aquatic events with a separate venue hosting water polo. The proposals are at a preliminary stage but the visualisations, by architect practice Yamashita Sekkei, show a trapezium-shaped ribbed structure raised on a podium with a similar poise to Denys Lasdun’s 1963 University of Liverpool Sports Centre.

Sea Forest Waterway

Canoe-Kayak (sprint), rowing

The prime waterside venue was very nearly scrapped in anticipation of rising costs. The site is currently an industrial area and fears over the costs of the demolition and relocation of existing factories almost pressed the organising committee to move the venue to an alternative site almost 300 miles away or scrap it entirely. Its retention will ensure rowing events take place within the impressive backdrop of the landmark Tokyo Bay Bridge. The plans involve the construction of a new rowing and canoeing facility located beside one the existing water channels that bisect one of Tokyo Bay’s several islands.

Ariake Arena

Indoor volleyball

At present Ariake is a relatively undeveloped peninsula to the north-west of Tokyo Bay. It is home to the Ariake Tennis Park which hosts the Japan Open and will host tennis events during the 2020 games. The centrepiece of the park is a 10,000 capacity arena known as the Ariake Coliseum (1985) but this will soon be joined by another showpiece venue for 2020 volleyball heats, the Ariake Arena designed by Kume Sekkei. Capitalising on its prime quayside location the new pavilion-like structure will be crowned with a convex roof resembling the inverted crest of a wave. After the games it will converted into a public gym.

EXISTING VENUES

Yoyogi National Stadium

Handball

The Yoyogi National Stadium is one of a number of venues that were constructed for the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games that will be in use for the 2020 games. Designed by renowned Pritzker Prize-winning Japanese modernist architect Kenzo Tange between 1961 and 1964, the 13,000 capacity venue hosted swimming and diving events at the 1964 games. In a relatively rare Olympic legacy accolade, since then it has been in constant use for a variety of sporting, musical and entertainment events and remains one of Tokyo’s foremost performance venues. Its most distinctive architectural feature is its billowing parabolic roof, an aspect that greatly influenced German architect-engineer Otto Frei when he came to design the famous tensile canopy roof for the Munich 1972 Olympic Stadium.

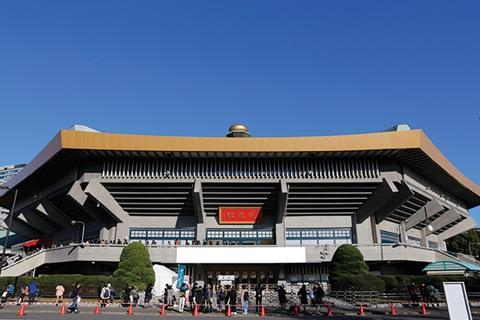

Nippon Budokan

Judo

Not only was the Nippon Budokan built for the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games to host judo events but it will also host judo events at the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games thus marking what must be a virtually unprecedented example of Olympic cost effectiveness and value efficiency. Immortalised in successive Live at the Budokan albums recorded by artists such as Bob Dylan and Ozzy Osbourne, its name translates as “martial arts hall” in English. As the albums suggest, it too has become an important staple in Tokyo’s entertainment and sporting scene in the 52 years since the 1964 games and is intensely proud of the fact that the Beatles were the first of hundreds of bands to perform there. Architect Mamoru Yamada’s imposing octagonal structure forms a curiously brutalist version of a Japanese temple.

Sapporo Dome

Football

The Sapporo Dome was designed by architect Hiroshi Hara and opened in 2001. The 41,000 capacity multi-purpose indoor sporting arena is one of only a handful of sporting venues across the world that incorporates unique retractable pitch technology where one pitch to completely slides above another. This enables the venue to be converted for use between football and baseball games. Sapporo has already hosted significant international sporting fixtures and was the venue for the England vs Argentina match in the 2002 FIFA World Cup for which it was built. With its pebble-like form and shimmering metallic skin, it is one of the most architecturally futuristic of all 2020 venues.

Tatsumi International Swimming Centre

Water polo

Tatsumi will share swimming events with the new aquatics centre by hosting water polo. Enjoying a prominent waterside spot to the north of Tokyo Bay, the venue was built in 1993 and hosts 3,600 spectators. Its distinctive design involves a number of curved white cylindrical barrels extending telescopically from each end of a central arch to cleverly form a scalloped semi-circle in plan, section and elevation. The venue houses two Olympic sized swimming pools for public and elite use and also hosts Japanese swimming championships.

Tokyo Big Sight

International press & broadcast centre

The venue formerly known as the Tokyo International Exhibition Centre is the largest convention and exhibition centre in Japan and was initially intended to host wrestling, taekwondo and fencing events for the 2020 games. However, reduced public funds forced these events to be relocated to a smaller conference centre to enable Big Sight to be deployed as the main media centre, thus avoiding the construction of a new one. Located beside the Ariake district adjacent to the planned Ariake Arena, the vast 1.1 million ft² complex was constructed in 1993. Its most distinctive architectural feature is a hulking titanium-clad tower comprising four inverted pyramids which contain conference rooms and a 1,100-seat reception hall all hoisted high above a quartet of soaring steel and glass plinths.

Izu Velodrome

Track cycling

Ambitious plans to build a new Olympic velodrome in the Ariake district were shelved as a cost-cutting measure late last year leaving this unprepossessing steel drum as the venue for track cycling events. Tokyo 2020 will therefore mark the first time since Athens 2004 when a new velodrome has not been constructed for an Olympic Games. Designed in 2001 by Gensler and Olympic velodrome veterans Schürmann Architects, the velodrome is the first in Japan to meet International Cycling Union standards by having a wooden track that is at least 250m long. The venue will be extensively renovated for the 2020 Olympics and its capacity will be increased from 1,800 to 4,300 seats.

No comments yet