Ten years after Richard Seifert’s death, Ike Ijeh asks how some of his most well-known works have shaped the architecture of modern Britain - and how controversial they really were

Although few outside the construction profession have heard of him, Richard Seifert changed London more than any architect since Christopher Wren. Even wily John Nash, who essentially forged the character of the West End as we recognise it today, failed to make a significant impact on the one area Seifert dominated: London’s skyline. If you live or work any higher than the 5th floor in the capital and look out of the window, there is every chance a Seifert building will glare right back at you.

Over the past three decades Foster and Rogers have pepper-potted the city with their numerous commissions. But their spawn fails to come even close to the astonishing 600-odd buildings Seifert inflicted on the capital and the scores more he built across the country.

It wasn’t just quantity Seifert was renowned for; he was essentially the man who brought the commercial tower block into the British architectural lexicon. Building primarily in the sixties and seventies, there is barely a city centre in the land that was spared his unmistakable brand of height and hubris. His uncompromising style, which veered from production-line modernism to bombastic brutalism, became naturally aligned to the tall building and he is rightfully credited as the man who introduced the high-rise aesthetic into the UK city centre. These are achievements for which he was worshipped by developers but reviled by conservationists and his is a career inevitably dogged by frequent bouts of bitter controversy, particularly in London.

As an architect businessman, Seifert cut a figure that is barely recognisable today. His manifest commissions and tactical prowess at outmanoeuvring planning law brought him commercial popularity and enormous wealth. He travelled in a chauffeur-driven Rolls-Royce, was allegedly one of the first to use a carphone and was said to be the UK’s first architect millionaire. Bespectacled, sharp-suited and shrouded in smoke emanating from his ever-present pipe, he was the epitome of the establishment gentleman.

But beneath the suave veneer lay a will of iron. His service in the army during the Second World War earned him the title of colonel, a sobriquet he insisted on maintaining throughout his career and one that reflected his impregnable self-righteousness. When submitting plans for Centre Point in 1962, he bluntly informed Westminster council that “we shall be glad to discuss any amendments but it is important that the bulk of the building should not be reduced”. Unthinkable today.

To commemorate last month’s 10th anniversary of Seifert’s death, we have picked a selection of some of his most famous works and gauged what impact they have had on the modern world today. Although Seifert’s reputation has grown since his death, history is always likely to judge him as a commercial architect who favoured quantity over quality. He was certainly no visionary and was too divisive a figure ever to command the respect or consensus nostalgia demands. This is reflected by the fact that within barely 25 years of their completion, an exceptionally high proportion of his buildings have already been demolished. (See “20 other buildings you never knew Seifert designed”, overleaf).

Nonetheless he did leave a prodigious body of work and, for good or ill, he helped craft the physical aspect of modern urban Britain. And for architects at least, his extraordinary commercial success enables the profession to take rare pride in a bygone age when the architect was king.

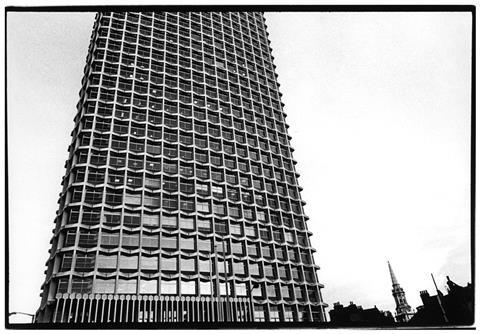

Centre Point, London

1963 - 1966

DESCRIPTION: Arguably Seifert’s most famous building, Centre Point was built as a 117m, 34-storey speculative office block for property developer Harry Hyams. Its unrelenting “beehive” grid of glass and concrete is one of Seifert’s most powerful experiments in brutalism.

CONTROVERSY: Huge. First there was the fact that permission was granted at all on a skyline then unsullied by tall buildings. Then there was its incorporation of one of London’s most illogical traffic junctions at its base, which astonishingly omitted pavements from a number of locations. Its brutalist style was also seen as an insensitive incursion on the historic terraces of Bloomsbury and Fitzrovia nearby. But by far Centre Point’s greatest sin was to remain empty over nine years after its completion. By so doing it became a symbol of commercial greed and the alleged ruination of London’s urban townscape and public realm for private interests.

CONTROVERSY RATING: 5/5

LEGACY: Architect Ernö Goldfinger dismissed it as “London’s pop-art skyscraper”. Centrepoint’s 1995 grade II listing aroused shock and satisfaction in roughly equal measure. Certainly one of its more damaging legacies was the precedent it set for insensitive high-rise development. And yet, despite becoming a symbol of sixties’ concrete brutalism, it has somehow managed to avoid much of the antipathy other exponents of the style popularly attract. Rumours abound that the entire block may be on the verge of being converted into flats, a move that is likely significantly to boost its allure.

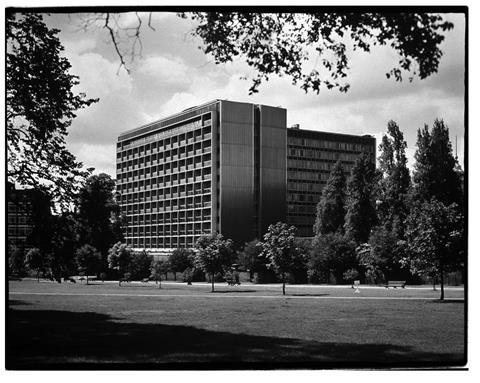

Royal Garden Hotel, London

1965

DESCRIPTION: Dismal luxury five-star 11-storey hotel on the edge of Hyde Park. One of a trio of hotels Seifert designed around the park.

CONTROVERSY: This is one of Seifert’s worst London buildings. He allegedly aroused the ire of Princess Margaret whose garden in next door Kensington Palace this behemoth overlooked. The building shows some of the most truculent elements of Seifert’s architecture: poor materials, weak massing, clumsy proportions, inappropriate scale and a complete lack of contextual sensitivity. Rammed against Hyde Park and looming menacingly over Kensington Palace and the grand Victorian villas behind it, the hotel has the effect of a bloated concrete book-end brutally slapped onto the entrance of a garden oasis. It would appear that the owners share something of this view: the entire building was re-clad in an anodyne if marginally less offensive aluminium straightjacket in 1997. This, however, fails to obscure the only realistic solution available for the Royal Garden ever since the day it opened: demolition.

CONTROVERSY RATING: 3/5

LEGACY: Minimal, other than it quickly became acceptable to clog up the perimeter of Hyde Park with insidious slabs of concrete (see Knightsbridge Barracks, London Hilton Park Lane, Royal Lancaster Hotel, Marble Arch Tower). It was, however, a huge commercial success, and proved Seifert’s aptitude in non-office sectors. It also led to his being commissioned to design a 2,000-bed hotel on nearby Gloucester Road, the largest in the world at the time. Mercifully, plans were shelved.

NatWest Tower / Tower 42, London

1971 - 1980

DESCRIPTION: The 47-storey, 183m NatWest Tower, Seifert’s last big project, was the UK’s tallest building until the completion of Canary Wharf Tower in 1991. Its staggered roofline, dynamic profile and soaring vertical ribs make it one of Seifert’s more dramatic compositions and a welcome shift from the bland rectilinear office slabs normally erected in the City.

CONTROVERSY: The NatWest Tower wasn’t the City’s first high-rise but it was its tallest and predictably provoked a storm of protest. Typically, Seifert enraged conservationists by calling for the demolition of the adjacent 1865 Gibson Hall as part of his scheme. The Hall was eventually retained in the final design. Even when finally complete, the tower’s problems continued. Its cantilevered construction required an enormous core, leading to a gross/net floor ratio of breathtaking inefficiency. Incredibly, the tower offers roughly the same amount of floorspace as the 25-storey 99 Bishopsgate next door. This rendered it incapable of accommodating the large trading floors required in the City before the 1986 Big Bang. Its famously constricted ceiling heights as well as the similarity of its floor-plan to the NatWest logo (always denied by Seifert) also attracted derision.

CONTROVERSY RATING: 4/5

LEGACY: Ironically, the 1993 IRA bomb that wrecked the tower’s curtain wall also helped improve its fortunes. NatWest moved out and was replaced by an array of new commercial tenants, chief among them the public bar that opened at the top, now one of the City’s most popular haunts. Admirably, Tower 42 as it was renamed, is now one of the few in the London that offers public access to its summit. It also introduced the super-tall US-style commercial skyscraper into the UK and without it it is highly unlikely the City would have built the Gherkin or Heron Tower. Although now a modern City symbol, its impact on London’s skyline widened the chasm between the City’s historic fabric and its tall buildings, a gap that later developments and the sustained lack of co-ordinated high-rise planning policy have left us no closer to bridging.

Sussex Heights, Brighton

1966 - 1968

DESCRIPTION: This 102m-high block of flats is still the tallest residential building on the south coast. Originally clad in white mosaic tiles, these had degraded so badly by 1995 that they were removed and the entire building was re-coated in a white elastomeric bonding paint. The flats are part of an exhibition hall and car park complex also designed by Seifert.

CONTROVERSY: Once again, Seifert exhibits a total disregard for local scale, proportion and character, here principally comprised of elegant Regency terraces. Even architectural critic Nikolaus Pevsner, instinctively sympathetic towards the modernist cause, called Sussex Heights “the most damaging modern building in the city” and it continues to assert unwarranted domination over Brighton’s townscape, skyline and seafront. To add insult to injury, it also flattened a Greek Revival chapel of 1824.

CONTROVERSY RATING: 4/5

LEGACY: Brighton and the south coast are now dotted with high-rises and they all have Sussex Heights to thank. Seifert’s influence is proven by the fact that, like Sussex Heights, the vast majority of these buildings remain residential rather than commercial. Tall buildings in the area, however, do remain highly contentious and in 2008 planners famously kicked out Frank Gehry’s proposals for a series of asymmetrical 20-storey residential towers on the site of a local sports centre. Remarkably, Sussex Heights itself has fared rather better. It now describes itself as a “luxury” block of flats and despite continued resentment about its urban impact, the residential format it offers - modern flats with balconies and uninterrupted sea views - has become one of the most sought-after property and lifestyle brands in the city.

Euston Station offices

1974 - 1978

DESCRIPTION: The current Euston station replaced Philip Hardwick’s neo-classical masterpiece of 1837. Although the concrete coffin that now masquerades as a station concourse was designed by faceless architect bureaucrats buried deep within the old British Rail, Seifert was involved in the project and is responsible for the miserable range of polished, dark stone-clad offices arranged around its entrance forecourt.

CONTROVERSY: The demolition of the old Euston station in 1962 was the biggest heritage controversy of a generation. It mobilised activists from as far afield as continental Europe and the US and, like the near-simultaneous destruction of New York’s spectacular Pennsylvania station, became an emblematic and defining moment in the bitter battle between modernists and traditionalists that raged throughout the sixties. The abysmal architecture of the new station and its surroundings only made matters worse. While Hardwick’s terminus, with its soaring grecian great hall and monumental doric arch (the world’s largest), was described by the RIBA as “one of the glories of the British railway age”, the Times lamented that its replacement was “the nastiest concrete box in London”. Euston’s destruction ranks as one of our greatest ever acts of architectural vandalism and Seifert’s involvement only cemented his folkloric status as pre-eminent heritage assassin.

CONTROVERSY RATING: 5/5

LEGACY: Enormous. The campaign to save Euston station may well have failed but such was the scale of international revulsion felt at its loss that it pretty much kick-started the modern conservation movement as we know it today. The abject failure of the listing process to save it (the arch was grade-II listed) also led to the tightening of government legislation to protect historic buildings and the foundation of the Victorian Society. One of the more intriguing ironies of London planning history is the proposition that the loss of Euston actually saved St Pancras, which was also earmarked for demolition by a ruthlessly unrepentant British Rail five years later. Today history has come full circle and now - as with so many of Seifert’s buildings - the avenging threat of demolition hangs over the much-reviled terminus. Although plans remain alarmingly vague, Network Rail has promised to demolish and rebuild it as part of a £2bn redevelopment scheme and plans are even under way to restore the Euston arch. Few Seifert buildings would be less missed.

20 Other Buildings You Never Knew Seifert Designed

LONDON: Blackfriars station (demolished) - Drapers Gardens, City (demolished) - Hilton London Metropole hotel, Paddington - Kings Reach Tower, Southbank - London Kensington Forum Holiday Inn hotel - New London Bridge House (demolished) - No 1 Croydon - Princess Grace hospital, Marylebone - Ramada Jarvis hotel, Bayswater - Sheraton Park Plaza hotel, Knightsbridge - Sobell Sports Centre, Holloway - Tolworth Tower, Kingston

ELSEWHERE: Anderston Centre, Glasgow - Alpha Tower, Birmingham - Centre City Tower, Birmingham - Concourse House, Liverpool (demolished) - Elmbank Gardens Tower, Glasgow - Gateway House Piccadilly, Manchester - Metropole hotel, Birmingham - Princess Margaret hospital, Windsor

No comments yet