Portsmouth now has an ingenious modern building that pays fitting tribute to an archaeological treasure

The new Mary Rose Museum in Portsmouth opens tomorrow (Friday 31 May) and neatly straddles two domains that have recently and somewhat surprisingly caught the public mood: ships and archaeology. Last year was the centenary of the sinking of the Titanic, and the commemorative opening of the new Titanic Museum in Belfast. It also saw the much-anticipated reopening of the Cutty Sark after a long period of restoration, as well as the completion of a major new extension to the nearby National Maritime Museum.

Archaeology, too, is enjoying an unlikely spell in the limelight. The recent discovery of Richard III’s skeleton underneath a Leicester car park sparked a flutter of fascination with history and revealed to a bemused nation the surreal ability of the past to interrupt the present. And the discovery last month of a treasure trove of Roman streets and artefacts under the three-acre construction site for the City of London’s new Bloomberg HQ was been described by archaeologists as the greatest ever haul of small Roman items found in the capital, now hailed as the “Pompeii of the North”.

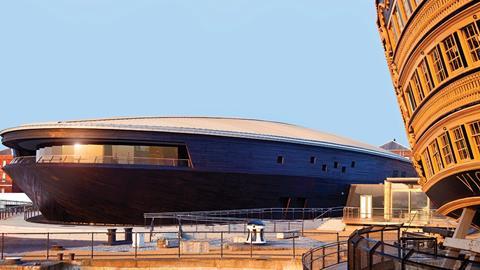

The building containing the ship looks, in fact, like a ship. Its oval form, inclined walls, distinctive prow-like balcony and virtually windowless facade all imbue it with a chirpy nautical air

But one of the greatest archaeological events of the twentieth century was the raising of the Mary Rose in 1982. Henry VIII’s legendary battleship, named after his beloved sister and now housed in a £27m Wilkinson Eyre and Pringle Brandon Perkins+Will-designed museum, was built in 1511 shortly after the king’s coronation.

Together with a smaller sister ship it formed the world’s first permanent naval fleet and thereby laid the foundations for future British imperial expansion and today’s Royal Navy. While harrying the invading French during the Battle of the Solent on 19 July, 1545, the Mary Rose catastrophically keeled over in just 14m of water and sank into Portsmouth harbour, killing virtually all of the 500 crew on board.

Embalmed in her watery grave for well over four hundred years, the ship’s 1982 salvage operation was the largest maritime archaeological excavation ever attempted, and it unveiled one of the world’s richest collections of sixteenth-century treasures. This included an astonishing array of almost 22,000 incredibly well preserved items that give a fascinating insight into Tudor life. Many are on display in the new museum and they range from shoes, pocket watches, medical apparatus and musical instruments to chopping boards, cannonballs, un-burnt firewood and even the skeletons of onboard vermin.

But the 1982 salvage also presented the Mary Rose Trust with a pressing challenge: how can the ship’s excavated hull, as well as the bounty of treasures it contained, be preserved and put on display to the public? The latter concern was temporarily addressed by the old Mary Rose Museum, which opened in 1984, heroically housed in an unprepossessing former boathouse that looked almost as dilapidated as its nautical namesake.

Preserving the ship’s hull, however, proved to be a more complicated matter. The half which had survived was saturated with about 120 tonnes of seawater. Although significant sections of the Mary Rose have beguilingly been left underwater for future generations to raise, a vast 280-ton, 20m x 13m section of the starboard hull, roughly one third of the ship’s total bulk, had been salvaged.

The ship’s carcass was then immediately transferred in nearby No. 3 dry dock at historic Portsmouth Dockyard, home of the Royal Navy. She was placed beside Nelson’s HMS Victory, another iconic battleship from the annals of British history, and has remained there ever since.

The drying process critical to preserving the hull began in 1994. That September, a water-soluble chemical solution called PEG was first sprayed onto the ship to prevent wood shrinkage and incredibly, this operation went on virtually uninterrupted until earlier this month when the sprays were finally turned off. Additionally, to maintain a constant warm temperature of 28ºC in order to aid the drying process, a tent-like structure was also erected around the dock to protect the hull.

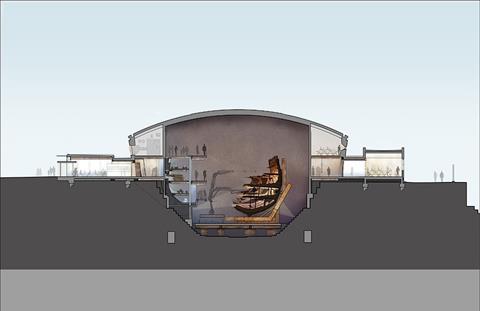

Therefore, the new museum building had to be constructed around the tent while the drying process continued uninterrupted within. And to complicate matters further, the dock itself is a scheduled ancient monument, so it was not possible to pile foundations directly into it. This unique set of physical and environmental constraints has had as much influence on the architecture of the new museum as the illustrious vessel it contains.

Ship in a bottle

The building containing the ship looks, in fact, like a ship. Its oval form, inclined walls, distinctive prow-like balcony and virtually windowless facade all imbue it with a chirpy nautical air which, despite its avowedly futuristic appearance, cleverly anchors it into its historic naval context. The hull-like analogy is further emphasised by its low-lying form, shallow saucer dome roof and the dark-stained timbers lapped tightly across its frame.

But this is no disposable piece of post-modern literalism. As Wilkinson Eyre director and co-founder Chris Wilkinson explains and as one would expect from a practice that prides itself on technological rigour, all these design characteristics are grounded in a taut technical stratagem.

“The museum’s shape is generated from toroidal geometry that is inspired from the form of a hull but not necessarily designed to imitate it. A far bigger driver was the fact we couldn’t pile directly into dock. Because of this we had to span across it, which generated a much lower building whose form and scale still subtly related to that of a ship,” he says.

We couldn’t pile directly into dock. Because of this we had to span across it, which generated a much lower building whose form and scale still subtly related to that of a ship

Chris Wilkinson, Wilkinson Eyre director

The environmental conditions required by the “hotbox” within which the ship was being dried also helped determine the building’s exterior form. “Because we were dealing with this highly controlled interior environment we wanted to create as little air and volume within the building as possible. So again a low, tight and virtually windowless envelope felt appropriate.”

And what of the distinctive dark-stained timber? “We wanted a neutral tone,” says Wilkinson, “that referred to the seaside vernacular but also had an air of mystery.”

And mystery is certainly what we have been given. With its blackened skin and stealthy profile, the new museum cuts a seductive and sombre form on the historic dock that pitches it in sharp contrast to its neighbours. Like a nebulous, ghostly void it lurks with amorphic ambiguity beside the riotous Gulliverian fantasia of old Victory next door. Opposing but not overwhelming the history that surrounds it, the museum’s enigmatic exterior is a spirited prologue to the sunken treasures buried within.

Designing inside out

If the outside of the new Mary Rose Museum has a nautical feel, however unwittingly, the resemblance does not stop on the inside. But here it is a far more intimate affair. For Chris Brandon, himself a marine archaeologist and principal of architect Pringle Brandon Perkins+Will, which was responsible for the interiors, it is clear who the star of the show is.

“The starting point was the Mary Rose. She is the jewel at the heart of this building. So we very much designed the museum from the inside out to create a controlled environment where light and atmosphere not only serve to recreate the experience of being on board a ship hundreds of years ago but also prioritise and enhance the impact of the artefacts on display.”

And this, gratifyingly, is exactly what the architects have achieved, principally by devising a brilliant central conceit. The salvaged starboard side of the ship is located on one side of the museum. Directly facing it on the opposite side a virtual port side has been recreated and it is within this that the bulk of the galleries have been located on three levels.

But the recreation is not a laboured literal copy of what the original would have looked like, more a blank, spatial interpretation of it. So the galleries themselves are sparse, barren chambers populated only by artefacts positioned as an exact mirror image of where they would have been located on the salvaged starboard side. Therefore visitors, by turning their heads between each side of the ship as they walk through the two halves, can visualise being onboard themselves.

The concept works as an architectural inversion, evoking the past as an abstract spectral twin rather than by pastiche. It essentially provides a negative copy in which all the ingredients of the original are safely stored, an inspired approach to the perennial challenge of finding ever more imaginative ways of making the past come alive. It also cuts to the core of what Brandon describes as the overriding concept for the museum interior: “The architecture reflects the ship but doesn’t replicate it.”

With the exception of the entrance lobby there is no natural daylight within the museum; galleries are conceived as dimly lit, low-ceilinged spaces that through scale and atmosphere rather than detailing, genuinely feel like the ship galleys they subtly seek to imitate.

Of the three levels of galleries, the lowest “below-deck” spaces have been designed as the most tight and claustrophobic and the uppermost “top-deck” galleries, directly under the roof, are the most spacious. Even the gradient of the walkways on each deck follows the configuration that would be found on an actual ship, with the route from stern to bow experiencing the sharpest incline and fall on the lower gangways before flattening out on the highest level.

Throughout, the dim lighting also ensures that visual attention is constantly diverted away from the architecture itself and onto the dazzling wealth of artefacts on display, all carefully spot-lit to resemble diamonds sparkling in a mine. “We didn’t want vast galleries” explains Brandon, “we wanted spaces where the scale actively promoted an intimate feel and atmosphere.”

The Mary Rose is very much the jewel at the heart of this building

Chris Brandon, Pringle Brandon Perkins + Will

However, there is one significant area of the museum where monumental scale is unavoidable and that is the point at which the Mary Rose itself, lodged across a central gangway from its recreated twin, comes into view. Its impact is breathtaking. Although the spraying has stopped, the hull itself is still being dried in a vast airtight chamber deep in the belly of the museum. There she now lies, visible in her protective cocoon only through windows cut into the sloping gangways next to her.

When the drying process is complete in 2018 the chamber will be dismantled and visitors will be able to stare from the gangways directly into the ship with no barrier in between. But even, now snatching glimpses through portholes, the improbability of the giant iconic hull, slumped in a gaping chasm like a jet fuselage wedged inside an airport terminal, is a surreal and exhilarating experience.

Architecture vs artefacts

Museum architecture usually falls into two opposing categories: those buildings that defer to the artefacts on display and those that vie with them. The latter category is unrepentantly espoused by celebrated venues like Gehry’s Bilbao Guggenheim and Zaha Hadid’s Maxxi in Rome. Even the glitzy crystalline sheen of the new Cutty Sark (another iconic maritime conservation project which Wilkinson and Brandon forcefully differentiate from their own as principally embodying an “engineering solution”) reveals a far more invasive architectural approach than that witnessed at the Mary Rose. While this more domineering design strategy is often considered a contemporary phenomenon, it actually has historical roots; neither the British Museum with its thundering colonnades or the spiralling atrium of Frank Lloyd Wright’s New York Guggenheim could hardly be considered reticent.

With its subdued emphasis on mood and atmosphere through manipulation of light and enclosure, it is clear that the Mary Rose adopts the more passive approach. Even the exterior’s “black hole” profile seems more akin to void than volume.

But let it not be thought that architecture takes a back seat at the Mary Rose simply because it rightly focuses attention on the wonders inside. From an engineering perspective, the creation of a flexible envelope that accommodates the evolving conservation of the ship within is an inspired technical solution.

Even more impressively than this, what the restrained architecture actually creates is a palpable and compelling sense of absence. And what floods into this vacuum is an intoxicating aura of the past, around which the building itself, like a time capsule or a tomb, becomes as potent a vessel for invoking history as the iconic shipwreck it contains.

PROJECT TEAM

client Mary Rose Trust

exterior architect Wilkinson Eyre

interior architect Pringle Brandon Perkins+Will

main contractor Warings

fit-out subcontractor 8build

services/structural engineer Ramboll

cost consultant/cdm co-ordinator Davis Langdon, an Aecom company

No comments yet