The crumbling Elephant and Castle shopping centre built in the 1960s is being reinvented as a mixed-use destination as part of Southwark council’s strategy to regenerate the area. Thomas Lane visits to see how it is coming along

London’s Elephant and Castle was once a place to pass through rather than linger. Most people are on their way to somewhere else, in a car or on a bus servicing one of 36 routes that pass through the district’s convoluted gyratory system.

Once known as the Piccadilly of the South thanks to smart shops and a vibrant nightlife, the area was badly bombed in the war and rebuilt in the 1960s and 70s. Forty years later it was tired, down at heel and dominated by constant traffic with the most distinctive feature being the Michael Faraday Memorial, a large stainless steel box housing a substation in the middle of the gyratory system. The other unusual sight was a pink elephant carrying a white castle on its back standing guard over the entrance to the dismal 1960s shopping centre.

This sense of decay in the area was exacerbated by the Heygate Estate, a crumbling, 1970s brutalist council housing estate notable for its huge slab blocks bearing down oppressively on the gridlocked New Kent Road.

How things have changed in less than 15 years thanks to Southwark council’s regeneration strategy. Somewhat controversially, the Heygate Estate was demolished in 2014 and replaced with Elephant Park, a Lendlease residential-led, mixed-use development with over 3,000 new homes, of which more than 2,000 are now complete.

The aggressive gyratory, infamous for being the most dangerous junction in London for cyclists, was partially tamed in 2016 by turning the Faraday Memorial roundabout into a peninsula by closing off the section of road adjacent to the shopping centre and introducing a two-way traffic system.

More recently, the second major strand to the Elephant’s regeneration is the new town centre replacing the 1960s shopping mall. Constructed in three phases (see box), the second, £449m by contract value phase is being built out by Multiplex and includes three residential towers with 485 build-to-rent apartments, 135,000ft2 of shopping and leisure facilities and 55,000ft2 of commercial space.

There is also a new building for the London College of Communication, part of the University of the Arts London, which will move from its current home just over the road. The old college will be redeveloped in the third phase and will include nearly 500 new homes, retail and leisure and a cultural centre.

A Thameslink station is situated on the east side of the town centre, the Northern line station to the west and the Bakerloo line station to the north on the opposite side of the road. A new ticket hall for the Northern line is being built as part of the scheme to cope with all the new residents now living in the area.

A short distance from the inadequate existing station, which offers lift-only access to the platforms, the new station will feature escalators and has been integrated into the northwestern corner of the new London College of Communication.

Originally serving just the Northern line, the ticket hall was redesigned in 2018, two years after the scheme received planning permission to accommodate the Bakerloo line extension to Lewisham. Should the extension go ahead, new platforms will be built so that these are closer to the new ticket hall and orientated towards Lewisham.

These must be at the level of the existing Bakerloo line, which is some five metres below the Northern line. This meant the original four-storey basement has had to be extended down a storey to provide level access to the platforms when these are built.

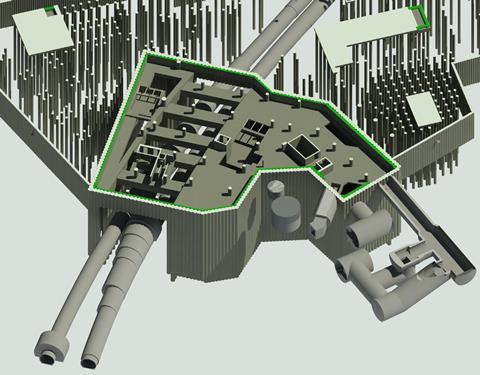

Although the Bakerloo line terminates some 150m to the north of the site, sidings for storing trains overnight run underneath the new station box. The columns supporting the 12-storey UAL building pass through this box including over the Bakerloo line siding tunnels.

As the tunnels could not carry these imposed loads, these have been bridged by transfer beams supported by piles on a capping beam on either side of the tunnel. The section of the station box over the tunnels was originally kept to two storeys to avoid breaching Transport for London’s five metre exclusion zone for work over its tunnels. Adding ticket hall capacity for the Bakerloo line including three additional escalators meant this section had to be extended down a level, taking the base of the transfer beams just 1.25m above the siding tunnels.

“With the original scheme, we had an exclusion zone of five metres to the top and three metres to the side of the siding tunnels,” explains Guy Wellings, deputy head of structures at engineer WSP. “But, when the new scheme came along, we had to basically disregard that and work with TfL to come up with a design that worked very close to their to their siding tunnels. We wouldn’t normally have chosen to do that, but we didn’t have much choice.”

There are six transfer beams supported by a secant piled wall to the west which was subject to water pressure, and a contiguous piled wall to the east. The loads from the columns bearing down on the tunnel mean the beams are enormous. Each is 20m long, 3.5m wide and 3m deep. The capping beam is 3.6m deep.

“Where there is a column coming down onto the capping beam, a transfer beam from the side and the pile from below, there is a very high density of rebar in one location. We had to deepen the capping beam to reduce that congestion,” explains Wellings’ colleague and structural engineer Chris Mager.

Mager adds that building such substantial structures so close to the tunnels necessitated extensive work and multiple assessments to demonstrate to TfL that the tunnels would not be affected by the work. The challenge was that the ground pressure around the tunnels means that these want to move towards any excavations as the balancing pressure in that area is removed. The tunnels are pushed sideways by the piling on either side of the tunnel and upwards when the area above is excavated.

What is in the new Elephant and Castle town centre?

The new town centre is being developed by Get Living with Delancey as development manager in three phases. The first phase, Elephant Central, was finished in 2018.

Located to the east of the phase currently being built out by Multiplex, this includes three 16 to 24-storey residential towers sitting on a three-storey podium. The towers include 374 rental homes while the podium houses retail and leisure uses including a gym.

This phase also includes Castle Square next door, a three-storey, timber-clad building housing small independent retailers.

The East site on the site of the now demolished 1960s shopping is the phase currently being built out by Multiplex. This also includes three residential towers ranging in height from 21 to 32 storeys. These will house 485 rental homes.

The shorter towers to the south sit on a two-storey podium housing retail while the 32-storey tower features a six-storey podium also housing retail. This phase includes the new London College of Communication which integrates the new Northern line ticket hall. And there is a freestanding four-storey retail building in the centre of the scheme featuring a steel exoskeleton structure. The development also includes a multiscreen cinema.

The West site is currently occupied by the London College of Communication, which will move to its new building in 2027. Some of the structure of the lower-rise building will be retained with the rest demolished.

There will be three residential towers ranging from 20 to 35 storeys housing 498 build-to-rent apartments. There will also be retail and leisure facilities and a new cultural centre. A contractor is yet to be appointed to this phase. Completion is scheduled for the mid 2030s.

Michael Waters, Multiplex’s project director, describes building the integrated ticket hall as the single largest challenge on the job. “I’ve built some pretty cool structures around the world, and this is definitely one of the hardest builds that I have undertaken,” he says.

The integrated ticket hall box is located within a much bigger, two-storey basement which has been constructed under most of the town centre. This features ramp access and 16 loading bays to supply the university and retail units above. The integrated ticket hall in the northwest corner is much deeper.

“It’s a basement within a basement,” explains Waters, who hails from Australia. “At our deepest point, we were 33m below street level, with five tiers of propping.”

The ticket hall construction was complicated by needing to get ahead on the 32-storey residential tower on the northwest side of the scheme. This tower encroaches onto one-third of the ticket hall box.

Waiting for the box to be finished before starting work on the tower was going to delay the programme, so top-down construction has been used for this part of the basement and conventional blue sky construction for the rest, which has added to the complexity of the job.

“We took the view that the risk profile was manageable if we kept an element of top-down to release the critical path of the structure above, but keeping a significant proportion of blue sky construction,” Waters says.

According to Mager, the tower was up to level 21 by the time the bottom of the ticket hall was reached. “It yielded all the results we wanted from it, and it was absolutely the right decision,” Waters says.

The excavations were complicated by extreme water pressure at tunnel level. A secant piled wall was used to keep the water out, but this had to stop short of the tunnels, leaving a gap.

The Harwich layer, which is about one metre deep and sandwiched between the London clay above the tunnels and the Lambeth Group just below the tunnel, is under extreme water pressure, between 155 and 180kpa. “It was like striking oil when you drilled through it. I’ve done a lot of groundworks and never seen anything like it,” Waters says.

Six wells fitted with pumps were sunk between the piles and tunnels to lower the water level and reduce the pressure. The transfer beams were constructed in a hit and miss sequence to reduce the risk of heave.

“If we had taken all the load off the area of the transfer beams, the tunnel would want to heave and there would have been movement,” explains Keegan Hudson, Multiplex construction manager for the basement construction. “The tunnel is lined with old, cast-iron segments which would have opened up and we would have flooded the Bakerloo Line.”

The work was intensively monitored, with alarms set to go off if the movement trigger levels were breached with mitigation measures ready to go. Wellings says the work went as planned.

With the difficult ground works out of the way, the integrated ticket hall structure will be handed over to London Underground next month [February] ready for fit-out. Above ground the job is coming along well. Ultra high performance fibre-reinforced concrete precast panels faced with brick slips have been used to clad the three towers. This cladding is now complete with apartment fit-out under way.

The 12-storey London College of Communication black glass reinforced concrete unitised cladding is also finished. The dramatic, black painted steel staircases that sail accross the generous atrium spaces have been installed with fit-out starting.

Lower down, the retail units and cinema facade installation is ongoing and work has started on the steel exoskeleton of the four-storey retail building with fit-out on the retail elements to follow.

The area has changed dramatically in the last 15 years. In a sure sign of gentrification, a Gails bakery recently opened in nearby Elephant Park.

Not all vestiges of the old Elephant have been swept away, however. The pink elephant statue has been restored and will take pride of place in the new town centre when this completes in 2026.

Project team

Client Elephant & Castle Development UK owned by Get Living

Development manager Delancey

Architect Allies and Morrison

Cost consultant Gardiner and Theobald

Structural engineer WSP

Services engineer Hoare Lea

Façade engineer Inhabit

Landscape architect Gillespies

Main contractor Multiplex

Piling and concrete structures Morrisroe

No comments yet