In converting a 1930s police station into the Metropolitan Police’s new HQ, contractor Bam faced a difficult case. But noise reduction criteria, a cramped site and a high level of security were no match for Bam’s trusty team

‘Better call in Curtis Green” is not a familiar phrase. For decades, in popular fiction and common conversation, London’s police force has been referred to simply as “Scotland Yard”. Fortunately, after London’s mayor sold the Metropolitan Police’s New Scotland Yard home to developers, it was agreed that its replacement would keep the well-known name.

Part of the capital released by the sale is being used to fund the conversion of the former Whitehall Police Station, known as the Curtis Green Building, into the Met’s new home.

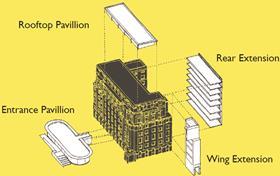

The £58m conversion, designed by Stirling prize-winning architect Allford Hall Monaghan Morris (AHMM), will transform the 1930s police station into a headquarters building fit for a 21st-century police force. AHMM’s competition-winning scheme includes the addition of a transparent public entrance pavilion at the front of the building, a glazed rooftop pavilion and a large full-height extension to the rear.

It is a complex project made all the more challenging by an immovable completion date of 31 October 2016. “We have a backstop date by which time the Met has to be out of the current New Scotland Yard building, which means that Bam has had to condense the design and overall construction programme to meet that deadline,” says Gavin Pantlin, project manager for the Curtis Green Building for main contractor Bam.

In a tight spot

Its task has been made all the more demanding by the site’s location in the heart of Whitehall, which placed restrictions on when noisy construction tasks could be carried out and required Bam to maintain a highly secure construction site. Security is intense, not just because the building will be home to the Met Police’s headquarters functions but also because of the project’s neighbours: to the south the site borders the Norman Shaw North building, home to parliamentary offices; to the immediate west is Richmond House, occupied by the Department of Health; while to the north is the Ministry of Defence’s main building.

To enter the tightly-hoarded site on London’s Victoria Embankment, each of the 250 operatives has to have a fingerprint scan. Next to the entry turnstile is a hand-shaped outline onto which each worker places their right hand, palm-down: one, two, three, four, five - the scanner’s red LEDs turn green around each of the fingers when the scanner matches their prints to those on record. Only when all of the LEDs have turned green does the turnstile grant them access.

The site entrance disgorges operatives directly outside of the new oval-shaped, glazed entrance pavilion. This has been constructed in front of the Curtis Green Building. The pavilion is perhaps the most obvious architectural manifestation of the Met’s desire to present a new, progressive and transparent face to the community it serves.

The pavilion’s curved glass walls are formed from a series of huge 3.5m x 2.4m double-glazed units, each weighing up to 900kg. As with much of this conversion, the entrance pavilion has been designed with physical security and operability in mind.

From the glazed entrance pavilion, visitors pass through into a newly created double-height lobby to enter the Curtis Green Building itself. The lobby is surrounded by meeting and function rooms on both the ground and first floors. Above this are six floors of open-plan offices on top of which sits a new rooftop pavilion.

The transparency theme from the entrance pavilion is continued inside the building; here Bam has punched a giant hole through the middle of the building’s reinforced concrete floor plates to open up the centre of the building. This glass-enclosed void now houses four scenic lifts that will transport workers between floors and up to the rooftop pavilion with its views out over the River Thames to the east and Downing Street to the west. The rooftop pavilion is intended to serve as a function room for the Met.

Investigation

It is a complicated conversion; to get the project to this stage in two years, Bam has had to focus hard on maximising construction efficiency.

The contractor won the design and build turnkey contract through competitive tender in December 2013. At the time of Bam’s appointment the design was still being developed and the scheme had yet to go to the planners. Bam exploited the opportunity afforded by its early appointment to offer construction and buildability advice to the design team of AHMM and engineer Arup under a pre-construction services agreement.

“One of the big advantages of being involved at RIBA Stage 2 was in enabling Bam to influence the design to get the fastest construction programme,” says Pantlin.

It was six months after Bam’s appointment that the planners gave the scheme the green light. Critically, from Bam’s perspective, planning permission included a requirement that the contractor adhere to strict construction noise criteria. “We only found out about the noise constraints after we’d committed to meeting the October 2016 deadline,” Pantlin says.

Raising the roof

Unusually, because there are no residents within earshot of the site, the planners required Bam to undertake its noisy operations early in the morning, between 6am and 9am, and in the evening between 6pm and 9pm. “Having MPs as neighbours meant that we couldn’t make any noise during the day,” says Pantlin.

One of Bam’s first construction tasks was also its most noisy: demolition of the building’s rear facade, removal of the roof, all staircases and lift shafts and opening up the floor plates. It was a task made all the more challenging by the Curtis Green Building having been designed and built in the run-up to the Second World War, which meant that it had a heavy-gauge, riveted steel structure that was encased in concrete and that had been designed to prevent progressive collapse in the event of bomb damage. “It was a very robust structure to cut and carve,” says Pantlin, tactfully.

To ensure its neighbours were undisturbed during the works, Bam had consultant Arup carry out predictive noise mapping for all the demolition and construction tasks. It also took the precaution of fitting an acoustic screen to the protective scaffold adjacent to parliamentary offices. “There was a lot of liaison with the neighbours to explain what works will be taking place, when and the noise levels that they could expect,” Pantlin says.

Bam used Brokk robotic demolition equipment and to use what Pantlin describes as “munching quiet” techniques for most of the demolition. As demolition progressed down through the building, the contractor seized the opportunity to compress the construction programme further by constructing new risers and service shafts as this phase of the works neared its close.

The contractor also took the opportunity to fully survey what remained of the building structure. It was helped by the Met’s crime reconstruction team who, conveniently, happened to be experts in carrying out point cloud 3D surveys. The gathered data was fed into the project BIM model and the project used PAS 1192-5:2015 specification for security-minded modelling, digital built environments and smart asset management to ensure secure information sharing arrangements were in place for the BIM model.

Crime reconstruction

Once the rear facade had been demolished, Bam set about erecting the new steel structure at the rear of the building. The original Curtis Green Building was C-shaped in plan, formed from a narrow rectangular floor plate flanked by two short wings. With AHMM’s design, the new steel structure infills the centre of the C to create larger rectangular floor plates; the structure also gives the modified building stability.

The new steelwork is supported on eight 750mm-diameter piles bored 32m into the ground in the small courtyard at the rear of the building. In addition, a further 30 piles, 350mm in diameter, were installed at the front of the building to support the new entrance pavilion.

With the piles installed, the site’s tower crane could finally be erected at the front of the building. The crane was essential in enabling the new steel structure to be constructed at the rear of the building. The new structure was built from steel sections that were no heavier than 7.5 tonnes. “It was all blind lifting. The entire structure had to be designed to be craned in over the building,” Pantlin says.

Erection of the steelwork commenced in April 2015 and was finished by December that year. This included construction of a new top floor of offices, which the architect had slotted in behind the existing facade, and the addition of the rooftop pavilion above. “Getting erection of the structure completed on time was key to staying on programme,” says Pantlin.

As the steel erectors raced the structure upwards they were closely followed by the cladding installers. AHMM selected a brightly coloured aluminium cladding system for the new rear facade, the colours of which were drawn from the surrounding streetscape. Once again, buildability issues influenced the choice of construction solution: “It’s a unitised system because it was quickest to install,” says Pantlin.

Protected from the weather by the cladding, fit-out of the new floor plates could commence. To maximise the floor-to-ceiling heights of the office floors, which are lower than would be in a conventional new-build office, a 350mm high raised access floor is used as a plenum to both supply conditioned air to the floors and as a cable distribution void. “It is a similar cabling arrangement to a dealer floor - all cabling is underfloor, which required careful coordination” says Roger Harding, director of real estate development for the Metropolitan Police.

BIM has been used to model all the building services, including the basement plantrooms, which the Met had point-cloud surveyed. “BIM was useful in helping to understand sequencing and access, particularly for large items of plant,” says Pantlin. He says the BIM model is “not fully data-rich”, but the information within the model is to a “fairly high level”.

Despite all this complexity, the project has progressed as planned and, with just four months remaining until the Met take up residence, Pantlin says the project is on schedule for an October handover. The building services are being installed on the office floors by Bam and its subcontractors. Bam’s FM team will also be involved after handover when a form of Soft Landings post-occupancy evaluation will be used to ensure the building services operation is optimised once the Met have taken up residence which, if the project continues on programme, should be very soon. Step forward, Dixon of Curtis Green.

Project team

Client London Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime

Main contractor Bam

Architect AHMM

QS and client’s project manager Arcadis

Structural and MEP engineer Arup

No comments yet