The Xiqu Centre for Chinese opera in Hong Kong soars above its constrained site with two theatres suspended above public space, by using some ingenious construction solutions

The recently released plans for London’s Centre for Music – as shown in last week’s Projects feature – have demonstrated that building large concert halls on constrained sites, though possible to do with creativity and ingenuity, is a very tricky proposition. However, even that venue’s City roundabout site presents less difficulty than the location of Hong Kong’s latest theatre; namely, suspended over a new public square and the tunnels of an underground railway station. But the response to this challenge is an extraordinary and inventive fusion of architecture and engineering, where a swirling aluminium facade that evokes the graceful sweep of a stage curtain conceals all manner of structural gymnastics within.

The £270m Xiqu Centre is the first of many cultural venues planned to be built in Hong Kong’s West Kowloon Cultural District (WKCD). Buro Happold provided engineering services on the building, which has been designed by the Canadian practice formerly known as Bing Thom Architects and now called Revery, designer of a host of theatre venues worldwide including the showpiece Arena Stage in Washington DC. The Xiqu, at the main entrance to the area, is one of the first venues to be completed and therefore acts as a literal and symbolic gateway to the cultural development as a whole. So it was important that its architecture set the tone for the quality and ambition to be found throughout the WKCD, (see West Kowloon).

Opera

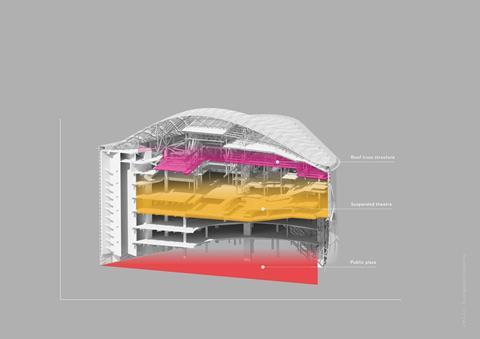

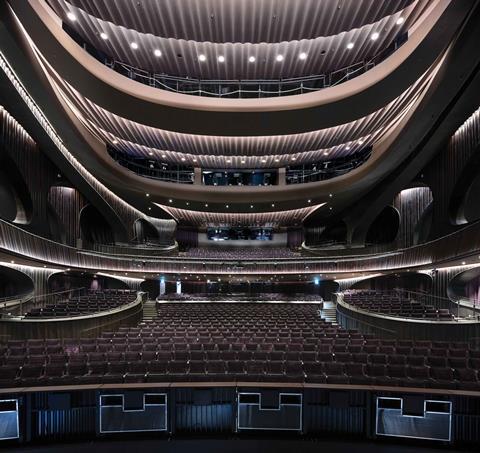

Xiqu is a traditional form of Chinese opera dating back to the third century and the new building forms its first permanent home in Hong Kong. The theatre comprises three principal spaces. First, a vast semi-enclosed public space underneath the building aids pedestrian circulation through the site and offers space for informal performances. Above this, a 200-seat tea house theatre where theatregoers can watch performances while drinking tea and eating dim sum, arranged beside retail, restaurant and rehearsal spaces. And located above these at the summit of the building, the star of the show – a 1,073-seat Grand Theatre suspended a full 25m above the ground.

Placing the building’s main auditorium in the vertical stacking arrangement described above gives a clue as to the scale of the structural challenges the building’s design and construction teams faced. But there were three very good reasons for placing the theatre at the top of the building, as Buro Happold associate structural engineer Tom Kember explains:

“First, we wanted to give the auditorium as much acoustic isolation as possible from the station and public space. Then we wanted to minimise vibrations from the station underneath the building. But first and foremost, because this new building essentially plays a gateway role to the rest of the West Kowloon Cultural District, we wanted the entire base of the building to be occupied by the new public space.”

In order to realise this ambitious structural proposal, a number of engineering solutions were initially explored. One included placing substantial long-span trusses underneath the main theatre. But, as Kember continues, “these would have severely compromised the public space below”.

The eventual solution that the engineering team decided on essentially involved flipping the long-span trusses from the bottom of the theatre to the top, then hanging the entire building structure down from them. As the primary support structure was now on the roof, this required the building to be built from top to bottom rather than from the ground up. It also required a relatively rarely used ‟strand jacking sequence” to fix the truss in place.

West Kowloon cultural district

The £2bn arts development aims to construct 17 landmark cultural and educational venues on 40 acres of reclaimed waterfront land and is Hong Kong’s largest ever cultural project. A diverse range of international architects is involved including the likes of Herzog & de Meuron and Farrells.

Other venues will include Herzog & de Meuron’s M+, a museum for visual culture scheduled to open next year and featuring a slender concrete slab set above a perforated podium. UNStudio has designed the 1,450-seat Lyric Theatre complex set to open in 2023 and Rocco Design Architects has designed the Hong Kong Palace Museum. As well as Xiqu, completed elements include an art park, a nursery park for the cultivation of rare tree species and the M+ Pavilion.

Top down

The building frame is supported by six gigantic 45m-high concrete columns, which reach to almost the top of the building. The columns were built using the same jump-form construction that would commonly be used on a tall building and are arranged along the perimeter of the building plan, which measures approximately 90m x 80m. Only one column is visible towards the edge of the public space, their perimeter location ensuring that the public area underneath the atrium remains a column-free space.

The columns support a steel primary truss structure that essentially forms the roof the building. As the entire building is effectively hanging from this truss, the trusses are made from high-strength steel and are almost 7m deep. A smaller secondary steel truss structure is located at the base of the main theatre and provides a roof for the public space as well as additional loading strength and stability for the structural frame. Once the primary roof truss was in place, work could start on the rest of the building below while being concurrently carried out on the roof, this saving time.

As part of the top-down construction sequence, after the columns were in place the primary truss structure was built on the ground. It was hoisted into place a full 45m off the ground by the use of a process known as a strand jacking sequence, mentioned above. This is primarily used to lift extremely heavy loads into place and involves steel cables within a hollow hydraulic cylinder being gradually clamped and released upwards to slide heavy objects up. At Xiqu, 12 jacks were used, two attached to each permanent structural column.

The roof truss being lifted weighed an extraordinary 1,800 tonnes, over half the weight of the Eiffel Tower. The truss also measured almost 7m deep and spanned over 45m. The lift was constructed in two parts, the first jacking the truss halfway up the column and lasting six hours. The jacks and structure were then locked into this position for approximately one month to enable additional temporary bracing to be installed to ensure horizontal stability. The truss was next jacked up into its first position in an additional six-hour sequence. Bearing beams were then used to secure the truss to the top of the columns and help transfer the weight of the truss from the jacking system to the six permanent columns.

Kember reveals that the strand jacking process offers a number of advantages. “It removes the need for a big temporary works platform and it also removes the risk of construction workers working at height.” While he concedes the process is used “relatively rarely”, he also recalls its use in the construction of the O2 Arena inside London’s Millennium Dome, where “strand jacking enabled the arena auditorium to be built inside the dome without the need for cranes, which would have been impossible to fit beneath the dome’s roof.”

Cover

The building’s structural complexities did not just pertain to its roof but also its dynamic facade. The facade is intended to give architectural expression to two conceptual ideas: first the Chinese principle of “qi”, fluid movements prompted by vital energy believed to circulate around the body in currents. And secondly, the idea of a stage curtain enclosing the theatre.

Accordingly, the building is clad in an aluminium curtain wall concealed behind a veil formed from a series of 2.5m-long curved aluminium fins. The twisting fins flow around the building envelope in a manner conceived to evoke fluidity and movement. Each fin is anodised to enable it to weather naturally and its form, position and composition refined through 3D-modelling technology.

At each curved corner of the building the aluminium fins parts to form an opening, which acts as an entrance to the public square. The parting of the fins also provides an opportunity to reinforce the drawn stage curtain analogy. Kember describes how the process of aligning the various “curves, cutaways and openings” within the facade with the inner structural frame of the building proved to be one of the most “geometrically complex” parts of the project.

The aluminium facade is joined at the top of the theatre by a ring beam that runs the full perimeter of the building. The beam is formed of a box truss clad with aluminium panels and is about 38m above the ground. While the cladding is not suspended from the beam, the box truss also supports the base of a perforated steel mesh dome that forms the top of the building and enables it to reach its full height of 50m. The dome is a visual solution that conceals the plant and flytower located at the top of the building.

WKCD chief executive Duncan Pescod describes the Xiqu Centre as a “defining moment in WKCD history and a benchmark for venues designed to showcase traditional theatre.”

In this case an ancient cultural tradition has indeed been celebrated but has also been combined with some state-of-the-art structural and engineering solutions.

Project Team

Architect: Revery Architecture / Ronald Lu & Partners

Client: West Kowloon Cultural District Authority

Main contractor: Hip Hing

Structural and services engineer: Buro Happold

No comments yet