Faced with severe space constraints on the site of the former Odeon cinema in Leicester Square, Edwardian Hotels has built more than half of The Londoner underground. Thomas Lane uncovers the secrets of the world’s deepest habitable basement

The phrase “fitting a quart into a pint pot” perfectly summarised the dilemma facing hotel operator Edwardian Hotels when it decided to build its flagship hotel in one of London’s most famous destinations. Edwardian reckoned it needed 350 bedrooms to make the Londoner scheme viable. However, the south-west corner of Leicester Square is in the line of one of St Paul’s Cathedral’s viewing corridors, which keeps the sight of the cathedral clear from 13 points around London, including Greenwich Park to the south and Alexandra Palace in the north. This restricted the £300m project to eight storeys, meaning 350 bedrooms would fill the entire building – a challenge since planners stipulated the Odeon cinema formerly sat on site had to be integrated into the new scheme.

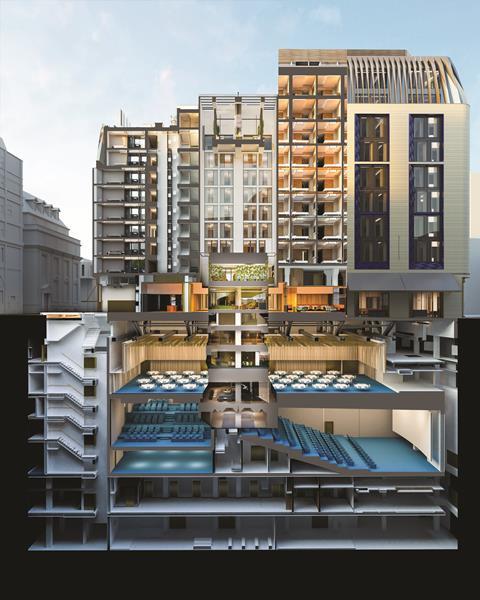

As the square is the centre for London’s film premieres, Edwardian wanted to include a 770-seat ballroom that would be suited to glitzy movie industry events, alongside restaurants and associated kitchens, bars and a swimming pool with spa. The only way to pack all these elements onto the 50m x 50m site was to dig down a long way. “Our basement for the Londoner is 31.2m deep,” explains Helen Taylor, project leader for architect Wood Bagot. “The difference between our basement and all others [deeper than 31.2m] is ours is fully habitable and mostly front of house. We think it is the deepest inhabited basement in the world.”

The Londoner Hotel

38 Leicester Square, London.

A 350-bed, five-star hotel with ballroom, spa, restaurants and two-screen cinema. Expected to feature the world’s deepest inhabited basement.

Size: 32,000m2, with 51% below ground

Project value:£300m

Procurement route: Construction management

Demolition started: April 2015

Main works started: August 2015

Completion date: June 2020

The Londoner’s basement will extend six storeys below ground. There are deeper basements around the world used for car parking, but these do not have to be bone dry, well lit and warm, with a constant supply of fresh air. And constructing such a deep basement in one of London’s busiest areas brings its own challenges including ensuring neighbouring

buildings are not affected by the excavation and getting rid of 75,000m3 of spoil. The groundworks were carried out by McGee, which has become something of a specialist in deep basements, with construction manager Blue Sky Building. The design was fully developed by architect Woods Bagot with Arup, which was responsible for the critical elements of the job including the structure, mechanical, electrical, and plumbing design and fire engineering.

London’s basement boom

London’s combination of rocketing land values and tough planning restriction has driven a boom in the construction of megabasements. A 2018 Newcastle University study concluded 4,650 residential basement planning applications had received planning in more expensive parts of London in the last decade. A total of 112 of these extended three storeys below ground, with some deeper than the height of the host house, spawning the phrase “iceberg basement”.

But those are dwarfed in comparison with recent non-residential ones. The British Library in Bloomsbury features a 24.5m-deep basement and more recently University College Hospital, in the same area, dug a basement 28.5m deep and 87m long by 67m wide to house its proton beam therapy centre. The most extreme example was an extension to Claridge’s Hotel in Mayfair, where a five-storey basement was hand-dug 25m below the existing building’s raft foundation without closing the hotel above.

Restricted depth

Fitting everything onto the site was a major challenge despite the depth of the basement. The team was restricted to a depth of 31m because of ground conditions. A layer of London clay extends 50m below ground with the Lambeth Group, a mixture of sands, silts and gravels underlying the clay. “We established we wanted to keep the piles in the London clay as the Lambeth Group is not stable, which means you need bentonite when piling to stabilise the ground,” explains Arup’s structural engineer and associate Rachel Cooper. “There was not space on the site for the bentonite silos.” The basement foundation piles needed to be 18.5m long, which determined the depth of the basement.

A spaghetti of telecoms, electric and gas cables and pipes, while Victorian brick sewers on the east and west sides needed diverting

The only way to fit all the elements needed to make the scheme viable was to extend the basement beyond the above-ground building footprint under the adjacent streets, except for the south side. The central London location meant these were clogged with a spaghetti of telecoms, electric and gas cables and pipes, while Victorian brick sewers on the east and west sides needed diverting. The biggest problem was a 2m-diameter UK Power Networks tunnel carrying high voltage electrical supply for the West End 14m below ground on the north-western corner. This could not be moved and the network stipulates that any excavations must be a minimum of 2m away from its infrastructure. “It potentially had a huge impact as it took a chunk off the corner of the ballroom and [could have] rendered the project unviable,” says Taylor.

Moving the other services to the opposite half of the road was complicated by the fact the space was already occupied. “We had to move the infrastructure in the furthest half of the road to make space for the utilities in the nearest half,” explains Cooper. “It took one and a half years to get permission and move the utilities.” Work started in 2014 and did not finish until the following year.

Arup created a huge 3D model of the underground infrastructure and used finite element analysis to establish the impacts of excavating nearer to the UKPN tunnel. Armed with this intelligence, Arup demonstrated it was safe to excavate to within 50cm of the tunnel. UKPN agreed to this with the proviso the tunnel had to be extensively monitored during the work.

Razor-sharp accuracy

With the underground infrastructure sorted out, McGee began basement construction in late 2015. The first step was to construct a secant piled wall around the basement perimeter. The depth of the basement meant the piles had to be very accurate. If these were just 1% away from true vertical, up to 600mm could be lost from the bottom of the basement. A 15m-long circular steel casing was carefully driven into the ground first to accurately guide the piling rig auger and help keep water out during piling.

Using a specially developed excavator with a long, telescopic arm that could reach to the bottom of the giant hole

Work started on digging out 75,000m3 of London clay in mid 2016. Working in clay has one big advantage – it holds very little water. “It was incredible we did not have to dewater,” says Ossie Falconar, the project director for contractor Blue Sky Building. “It made a huge difference to construction.” The clay was lifted into waiting 18-tonne lorries using a specially developed excavator with a long, telescopic arm that could reach to the bottom of the giant hole. The spoil removal was a carefully choreographed operation – up to 150 lorries visited the site a day with one filled every four minutes. McGee used sophisticated techniques to keep the lorries moving including cameras to monitor congestion and a traffic light system that indicated when exactly the right amount of spoil had been loaded into each vehicle.

Four sets of specially made braces weighing a total of 1,600 tonnes were used to stabilise the excavation. An array of movement monitors on surrounding buildings and CCTV inside the UKPN tunnel were used to keep a check for unwanted ground movement. The excavation completed without any unwanted movement issues and the team held a bottoming-out ceremony in February 2017, burying a time capsule 35m down with details of all the people working on the project.

The next job was to install the piles for the building and cast the 1.5m-deep basement slab. The braces were taken out as work progressed upwards since the intermediate slabs provide the necessary stability. A 425mm-thick, waterproofed concrete basement liner wall was built to keep the water out. The internal walls had to be completely dry so an inner blockwork wall has been constructed, separated from the concrete liner wall by a drained, ventilated and insulated cavity. Any water that soaks through the liner trickles down to a French drain under the slab and pumped out to the surface.

What’s in the world’s deepest inhabited basement?

The six-level basement at the Londoner houses virtually all the front- and back-of-house facilities needed for a 350-bedroom hotel. It also contains a two-screen Odeon cinema that had to be reinstated as a condition of planning.

A 770-seat ballroom occupies the two highest levels. Conference and meeting rooms are also located here, giving the area a total capacity of 1,100, alongside a private club and dining room on level one.

The cinema takes up the two floors below the ballroom and features box-within-a-box construction to acoustically isolate the cinema from the hotel. The swimming pool and spa are also located at this level. Level five houses a staff canteen, the main kitchen, a bakery, staff offices and a cold room. The sixth and lowest basement level houses plant.

Taylor says since some of the 400 staff spend most of their day below ground, it was important to ensure the back-of-house spaces were good quality. “We made sure all the fixtures and fittings were almost front-of-house quality and there is tunable lighting that follows circadian rhythms,” she explains.

The building features two offset atriums to serve the above- and below-ground areas. Taylor says it would have been “too overwhelming” to have one atrium running the entire height of the building. There are another three sets of stairs serving the basement and a total of 11 lifts.

Sent down

The basement includes two large clear span spaces – the ballroom and Odeon cinema. The double-height ballroom occupies approximately 40% of the first and second basement levels, with the two-screen Odeon located directly below this. The cinema also occupies two levels and was originally intended to seat 670 people but a change to sofa-style deluxe seating has reduced this to 240 viewers.

The scale of these spaces called for some heavy-duty structure to support the nine floors of hotel above. The answer is six trusses, which span the width of the ballroom. At 20.5m long, 2.85m high and weighing up to 63 tonnes each, getting these into central London and into position without causing havoc was a major challenge. The trusses were brought in at night under police escort along a carefully planned route that involved moving lamp posts to enable the long trailer to take sharp corners and a tight squeeze through Admiralty Arch on the Mall.

The basement can hold up to 2,500 people at peak times

An 800-tonne crane, supported on a massive temporary platform constructed over the basement, was used to lift the trusses into position. The operation was completed over a wet Valentine’s night in 2018.

The basement can hold up to 2,500 people at peak times, so needs a massive amount of fresh air. The pool, four levels down, requires much ventilation, as do the 13 kitchens and pantries. This called for three pairs of very substantial ducts to get air into the basement – the biggest are 6.5m by 2.5m in plan.

The plant on level six includes boilers, chillers and water tanks. “Getting all this gear down here was quite a challenge,” says Falconar. At first, the plant was lowered through the huge ventilation shafts using a builders hoist. As the job progressed, the hoist was replaced by a permanent lift big enough to hold a small car.

According to the project team, ensuring the highly complex services fitted neatly into the building without clashes was one of the most challenging parts of the job. “You had to lock yourself into a room for a week to work it all out, then you had to do it again and again to make sure you got it right,” says Taylor.

The team turned to a software tool called Jira, originally used to debug software, to help with the job of co-ordinating the services. Anyone that detected a clash could include a screenshot of the issue, assign a tag to it and indicate who was responsible for fixing it. Once the fixer had resolved the issue, they could sign this off within the software.

Moving upwards, the above-ground elements are relatively straightforward in comparison. The switch from big, open basement areas to the bedrooms above called for complex transfer structures. The same was true of the ductwork, which needed to switch from the vast ducts used to service the basement to smaller, building-sized ones for above-ground services. The bulk of this transition takes place at ground-floor level, which accommodates the hotel concierge, a loading bay and the separate entrance to the cinema. The air intakes and extract for the basement are located just above that level. The building completes this summer and Edwardian have even taken an advance booking for the ballroom which vindicates its approach to this complex scheme.

Project Team

Client: Edwardian Group

Architect: Woods Bagot

Structural and services engineering: Arup

Construction manager: Blue Sky Building

Planning and cost consultant: JLL

Interior designer (front of house): Yabu Pushelberg

Interior designer (back of house): Woods Bagot

Contractor (basement, shell and core): McGee

Contractor (fit-out): EE Smith

Contractor (MEP): Halsion

Kitchen consultant: Humble Arnold

Cladding: GIG Facades / Grants / Darwen Terracotta

Facade artist: Ian Monroe

No comments yet