Multi-storey car parks may not traditionally have been seen as desirable real estate, but with city parking lots becoming increasingly valuable spaces, a lucky few are being repurposed as everything from luxury hotels to micro-flats.

When Brewer Street car park opened in London’s Soho in 1929 it had gilded waiting rooms for chauffeurs, ladies’ changing rooms exquisitely decked in lacquer and gilt and had been imagined by Scottish architect JJ Joass, one of the leading commercial designers of the day.

This was the art deco period, which famously prioritised glitz and glamour. But even more importantly, it was the machine age, an extraordinary period when the 20th century came into its own as the great cultural incubator of technological progress and consumer choice – both embodied in the inexorable rise of the motor car. So in the 1920s and 1930s, multi-storey car parks were motorised urban palaces.

Today of course, the situation is very different. In this country at least it is difficult to summon a type of building more bleakly associated with notions of failed, dystopian and malignant urbanism than the concrete inner-city multi-storey car park. The shift started with the collapse of modernism in the 1970s and has accelerated sharply in recent years with the widespread adoption of environmental, social and political measures to dissuade car use, particularly in our city centres.

There is also the advancing reality of the driverless car. There are an estimated 105 million parking spaces in the US, almost a space for every adult man or woman in the country. Google has claimed that its driverless cars could free up areas of urban parking “the size of Connecticut” for schools, hospitals and housing. While transport expert and ex-London mayoral candidate Christian Wolmar dismisses this as a “dangerous fantasy for a whole host of social, technological and legal reasons”, he does concede that “car use is inevitably declining and rising land costs and tacit political measures over the past 15-20 years mean the idea of a multi-storey car park in the middle of a city is increasingly untenable”.

This leaves a pressing architectural question: what happens to all those inner-city car parks built to serve an age of the motor-car that has passed? Can they be reused or converted? Or does the end of our love affair with the private car and the possible rise of the driverless car mean that urban car parks are now technologically, functionally and economically redundant? Is their demolition is now inevitable?

Demolition

While it may initially be seductive to dismiss car parks as architectural nonentities ripe for the wrecking ball, some of their earlier incarnations are now being treated as important examples of recent heritage, as Twentieth Century Society director Catherine Croft explains. “Many car parks are associated with architectural monstrosities. But they can be sculpturally exciting buildings that strongly affirm the notion of the building as a machine. While technically not a car park, the old Fiat Factory in Turin, Italy, with all its mechanical lifts and swirling ramps is a great example.”

The future fate of car parks is also complicated by another heritage-related development that has evolved over recent years. Brutalism, the 1960s and 70s architectural style that spawned thousands of car parks across the world, was once broadly reviled but has recently enjoyed the kind of renaissance that now makes automatic demolition of its better buildings contentious.

Get Carter, the classic 1971 thriller film starring Michael Caine, was partially filmed at Gateshead’s infamous Trinity Square car park. In 2002, even the founder of the film’s appreciation society dismissed the Owen Luder Partnership-designed building as “ugly”. But today, despite having been demolished, the car park is feted by many as an enduring icon of mid-20th century brutalism, the loss of which should have been prevented at all costs.

But even for those who accept that the demolition of buildings like Trinity Square was a mistake, there are still two other critical considerations that make the retention and conversion of urban multi-storey car parks problematic: rising inner-city land values (particularly in London) and restrictive floor-to-ceiling heights.

“The low floor-to-ceiling heights are probably the biggest problem.” explains the Twentieth Century Society’s Croft. “Ceiling heights were generally higher in 1920s and 1930s buildings because the cars were bigger. But they’d become smaller by the 1960s, which generally makes those car parks harder to convert.”

One such car park where this constraint is dramatically on display is in central London. Its proposed controversial demolition is also rendered more likely by the fact that it now sits in an area marked by some of the most expensive urban real estate values in the world. It thereby illustrates the twin handicaps that are likely to prove the biggest obstacles to retaining urban car park structures in the future.

Welbeck Street

Welbeck Street multi-storey car park is located just north of Oxford Street in London’s Marylebone. It was built in 1971 by Michael Blampied’s practice, Blampied & Partners, for Debenhams’ flagship department store, behind which it stands. But last year Westminster city council controversially granted planning permission for the building to be demolished and replaced by an allegedly Byzantinesque luxury hotel, designed by Eric Parry Architects.

A decade ago the move might not have caused much of a stir. But Welbeck Street is brutalist building. Or at least a brutalist-lite building – in its tracery-like facade of interlocking triangular eyelets, the structure wears its brutalism more as playful surface jewellery in the manner of nearby Centre Point rather than the more visceral volumetric aggression for which the style is renowned. But the point is that the positive revisionism brutalism has enjoyed of late has now left many concerned about the car park’s fate, even if it remains unlisted.

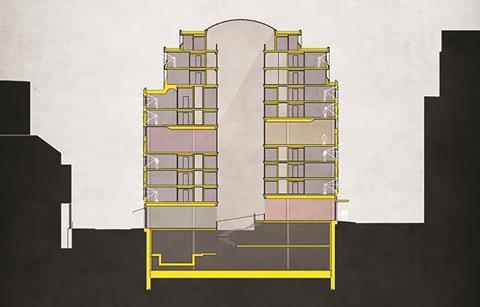

In fact, east London practice JAA Studio is so concerned that it has drawn up speculative plans to convert the building into a hotel by demolishing the internal structure but retaining the facade. Croft, whose Twentieth Century Society fully supports the alternative plans, describes them as “clear, sensible and exciting”.

One of the principal problems that Parry says stopped him doing the same was the meagre floor-to-floor height of only 2.1m, a height that regulates the external subdivision of the facade.

He also claims that due to the building’s unconventional structure, retaining the facade would require so much structural propping that it would reduce the internal floor area below commercially viable means.

But JAAs claims to have overcome these problems by rehanging the precast concrete panels of the current facade onto a newly built internal structural frame, which would enable it to maintain the same external appearance. The subdivision problem would be solved by setting a higher restaurant level at the centre of the new building’s section, which would be aligned to the external openings. Then new lower floors would be set below and above this new floor, with window openings either at the top or the bottom of each storey.

“It won’t necessarily be cheap,” concedes JAA director Alessio Cuozzo, “but neither will the proposed scheme. Moreover, I fully appreciate how difficult it is to adapt multi-storey car parks – most other buildings, such as police stations, schools or offices are designed to be used by people – car parks aren’t. The restricted floor-to-ceiling heights are also a huge problem. And I admit many car parks are ugly!

“But this one isn’t. It’s a striking and much-loved building that’s very much of its time and whose demolition would waste a huge amount of embodied energy. It was also frustrating that both Historic England and the approved scheme kept on making arguments against the existing building that weren’t really based on anything. We’ve proved that new internal slabs don’t have to clash with the exterior facade and how a new structure can be made to work with it.”

For Cuozzo, it is not just declining car use that has imperilled Welbeck Street but the location-driven economics that invalidate the commercially inefficient allocation of expensive land that car parks embody. “The site was sold for £100m. That immediately imposes the need for a building to provide a sizeable financial return. The time to protect these buildings is before they’re sold, even if that means a new tier to the listing grades – afterwards it’s too late.

“And sadly, that’s probably the case here. Despite our efforts, we’re at a stage where the building is probably going to be demolished, and that’s a shame. In the hands of a different client there might have been something really cool about converting a car park to a hotel.”

Peckham Levels

While conversion has not been the selected route for Welbeck Street, there are an increasing number of UK projects where innovative new uses have been found. In Stratford, east London, the 2012 Olympic Games prompted the conversion of the top floor of a shopping centre car park overlooking the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park into a community and cinema leisure space. Roof East has proved so popular that it has now been permanently retained.

Even more ambitiously, in the southern US city of Atlanta a downtown multi-storey car park overlooking one of the most congested stretches of highway in the country was converted in 2014 into micro-flats, as the result of a project begun by the Savannah College of Art and Design. Each unit costs as little as £28,000 to buy and is based on the 135ft² grid of a US parking space.

And most recently, an underused 1970s multi-storey car park in south London has been imaginatively repurposed as a creative and artistic hub. Carl Turner Architects, which specialises in combining innovative workplaces with social enterprise, has transformed seven levels and 8,700m² of a bleak and semi-derelict multi-storey into a series of co-working studios, workshops, 3D-print rooms and even kiln chambers for start-up enterprises and more established arts and culture organisations.

The scheme benefits from the extraordinary success of the rooftop bar and cinema already established on the car park’s top two floors since 2015. But unlike these ventures, Turner’s interventions are temporary and, at present, are scheduled to be in place for only five years.

Accordingly, architecturally the scheme has what Turner himself calls a “light touch and minimal approach”. The concrete floor has been left in place, with some road signage retained. Partitions are lightweight OSB panels and new windows were slotted in internally to avoid the need for scaffolding. And at the centre of the block where natural light is most restricted, less inhabited spaces such as 3D printing labs and photography studios have been placed.

“It’s essential that we retain and celebrate the material qualities and character of the existing car park’s concrete structure,” explains Turner. “To foster creativity, the project acts as a blank canvas and allows its users to feel free to experiment without worrying about damaging or altering the space.”

Beaumont Hotel

Such a venture seems the ideal reutilisation of the car park building type, with its robust exposed surfaces. And while it is unlikely the land values in London’s West End could accommodate the kind of grassroots venture possible in hipster-gentrified Peckham, even central London offers multiple examples of car park conversions.

The 1923 Bluebird cafe on the King’s Road in Chelsea and the 1931 McCann advertising headquarters in Bloomsbury both occupy stunning restored art deco buildings, and both benefit from the higher floor-to-ceiling heights the period afforded. And as Cuozzo mused, one of the most recent examples of this trend is the luxury Beaumont Hotel in Mayfair, converted from the (listed) 1926 Balderton Street car park by ReardonSmith Architects in 2014.

Senior associate Rafal Pasek recalls: “In terms of function and structure it was relatively easy to convert. While the internal structure itself was strong and in very good condition, we couldn’t retain it because chemical fumes and oil spillages from cars, wash areas and mechanics meant it had suffered a lot of staining and the steel reinforcement was incredibly corroded. Also, thanks to the deep plan, some of the structural beams were incredibly tall.

“But unlike Welbeck Street, we benefited from floor heights of around 4m, so we’ve maintained the same levels, which obviously lines up with the facade. Also, the external facade was in great shape as it had been faced with a pioneering cement mix that made it incredibly robust. The client wanted a hotel but this kind of building could be converted into anything – it’s a valued piece of heritage and it’s important it’s preserved.”

Car parks of the future

So what might the future have in store for urban multi-storey car parks? None of the aforesaid examples show car parks being retained for their original function so might the building type vanish entirely from our urban centres?

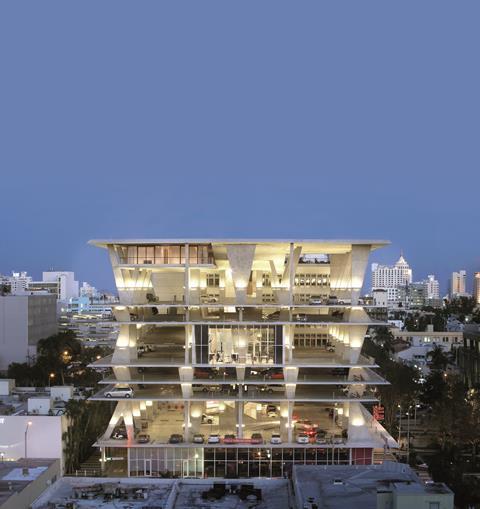

Not in America, it seems, where Herzog & de Meuron’s spectacular 1111 Lincoln Road scheme in Miami Beach, Florida – essentially a sculptural series of thrusting concrete platforms – shows that in the country that invented the car, the multi-storey is alive and kicking. The bars and restaurant within the scheme have become destinations in themselves. “It’s a wonderful, unique example. It brilliantly captures the glamour and excitement once associated with this building type,” opines Croft. She suggests the mixed-use format might be workable here. “1111 Lincoln Road incorporates bars and restaurants, and even the famous Preston bus station [in Lancashire] has a car park above the station. What also makes schemes like Peckham Levels so interesting is that they use the good views from the top of multi-storeys for recreational uses.”

The city of Aarhus in Denmark has another solution. Underneath its Dokk1 public library, the largest in Scandinavia, Schmidt Hammer Lassen has built Europe’s biggest automated car park. Robotic platforms whisk 1,000 cars underground away from public view and, crucially, without using expensive above-ground real estate.

Even in the UK, a new generation of architecturally distinctive city centre multi-storey car parks can still be found at sites such as Victoria Gate in Leeds and the Paradise Street Interchange in Liverpool. But crucially, these are not the standalone structures of yesteryear but are built as part of a shopping centre that they exclusively serve.

While the urban multi-storey car park may not disappear entirely, a host of commercial, social and political changes make it unlikely to play as big a role in this century as it did in the last. Despite occasional flourishes of architectural brilliance, it is a building type that perhaps few will mourn. But its loss speaks volumes about how our cities and societies are evolving.

No comments yet